The hidden “backup heater” in fat that could help treat obesity

WashU Medicine researchers have identified a hidden pathway inside brown fat — the body’s calorie-burning “good” fat — that could open new doors for treating obesity and diabetes.

“The pathway we’ve identified could provide opportunities to target the energy expenditure side of the weight loss equation, potentially making it easier for the body to burn more energy by helping brown fat produce more heat,” said Irfan Lodhi, PhD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism & Lipid Research. “Boosting this kind of metabolic process could support weight loss or weight control in a way that is perhaps easier to maintain over time than traditional dieting and exercise. It’s a process that basically wastes energy — increasing resting energy expenditure — but that’s a good thing if you’re trying to lose weight.”

The research points toward novel ways to harness brown fat’s natural ability to burn calories. Unlike white fat, which stores energy, brown fat converts calories from food directly into heat, helping keep us warm in the cold. Scientists have long been interested in activating brown fat to support weight loss, but much of the focus has been on mitochondria, the cell’s main energy producers. This study uncovers a significant backup system that kicks in when this primary one is impaired.

The team found that small cellular compartments called peroxisomes can also produce substantial heat. At the center of it all is a key protein within peroxisomes called ACOX2.

The ‘backup heater’ in action

When exposed to cold, peroxisomes in brown fat increase in number — an effect even more dramatic when the main mitochondrial heat protein is missing, offering strong evidence that peroxisomes act as a compensatory heater.

Mice lacking the ACOX2 protein in their brown fat struggled to tolerate cold, showed worse insulin sensitivity and were more prone to obesity on a high-fat diet. Conversely, mice engineered to have high levels of ACOX2 showed increased heat production, better cold tolerance and improved metabolic health even on unhealthy diets.

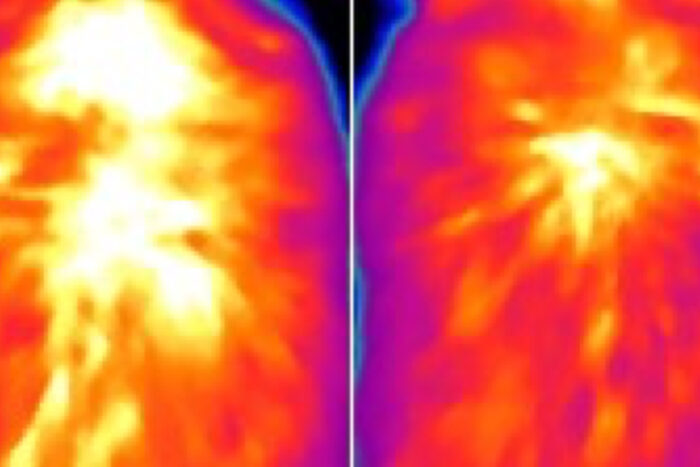

Using a custom fluorescent heat sensor and infrared imaging, the researchers confirmed that ACOX2 activity directly heats brown fat cells.

The path from mice to medicine

The fatty acids processed by ACOX2 occur naturally and are also found in dairy and certain gut bacteria. This raises the possibility of dietary interventions — like specific foods or probiotics — to boost this pathway.

“While our studies are in mice, there is evidence to suggest this pathway is relevant in people,” Lodhi said. “Prior studies have found that individuals with higher levels of these fatty acids tend to have lower body mass indices. But since correlation is not causation, our long-term goal is to test whether dietary or other therapeutic interventions that increase levels of these fatty acids or that increase activity of ACOX2 could be helpful in dialing up this heat production pathway in peroxisomes and helping people lose weight and improve their metabolic health.”

Lodhi and his colleagues are now investigating possible drug compounds that could activate ACOX2 directly, moving their discovery closer to clinical applications.