Where science and family courage collide

On a quiet evening in St. Louis, MO, Carrie Richardson is sitting next to her daughter Hannah. “I’m 44 years old and I have Alzheimer’s,” she says softly. “It sucks.” Her honesty is raw, but her determination has always shined brighter. For Carrie and her family, Alzheimer’s is not a distant fear — it’s a daily reality.

For generations, the disease has haunted their family and others around the world. Parents lost in their 40s. Brothers and sisters diagnosed before they saw their own children grow up. But over the last two decades a series of clinical trials is changing that, offering a path forward never thought possible for those with the disease. Carrie joined the DIAN Observational Trial early on. Hannah calls her mother her hero. “She has given so much, without knowing if she’s going to get anything in return. That takes true bravery.” Inspired by her mother’s courage, Hannah enrolled and became the first participant in the Primary Prevention Trial at WashU Medicine and is pursuing medicine to support families facing the same devastating diagnosis.

Intervening in the silent years

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, affecting more than six million Americans today. And it is relentless. “Alzheimer’s disease causes microscopic damage in the brain,” explains Randall J. Bateman, MD, the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Distinguished Professor of Neurology. “Amyloid plaques outside the neurons clump together and disrupt the connections between neurons, while tau tangles inside the neurons damage their ability to communicate and function. These changes can begin 10 to 20 years before the first symptoms or memory problems appear.”

This means that for many the disease is already advancing long before it announces itself. By the time symptoms emerge — confusion, fading recognition, difficulty completing familiar tasks — brain cells are already sick and dying. “Eventually patients can no longer care for themselves. They become bedbound, unable to walk or eat,” Bateman says. But it is in this window — the silent years before symptoms — that WashU Medicine scientists are determined to intervene.

Building on a global foundation

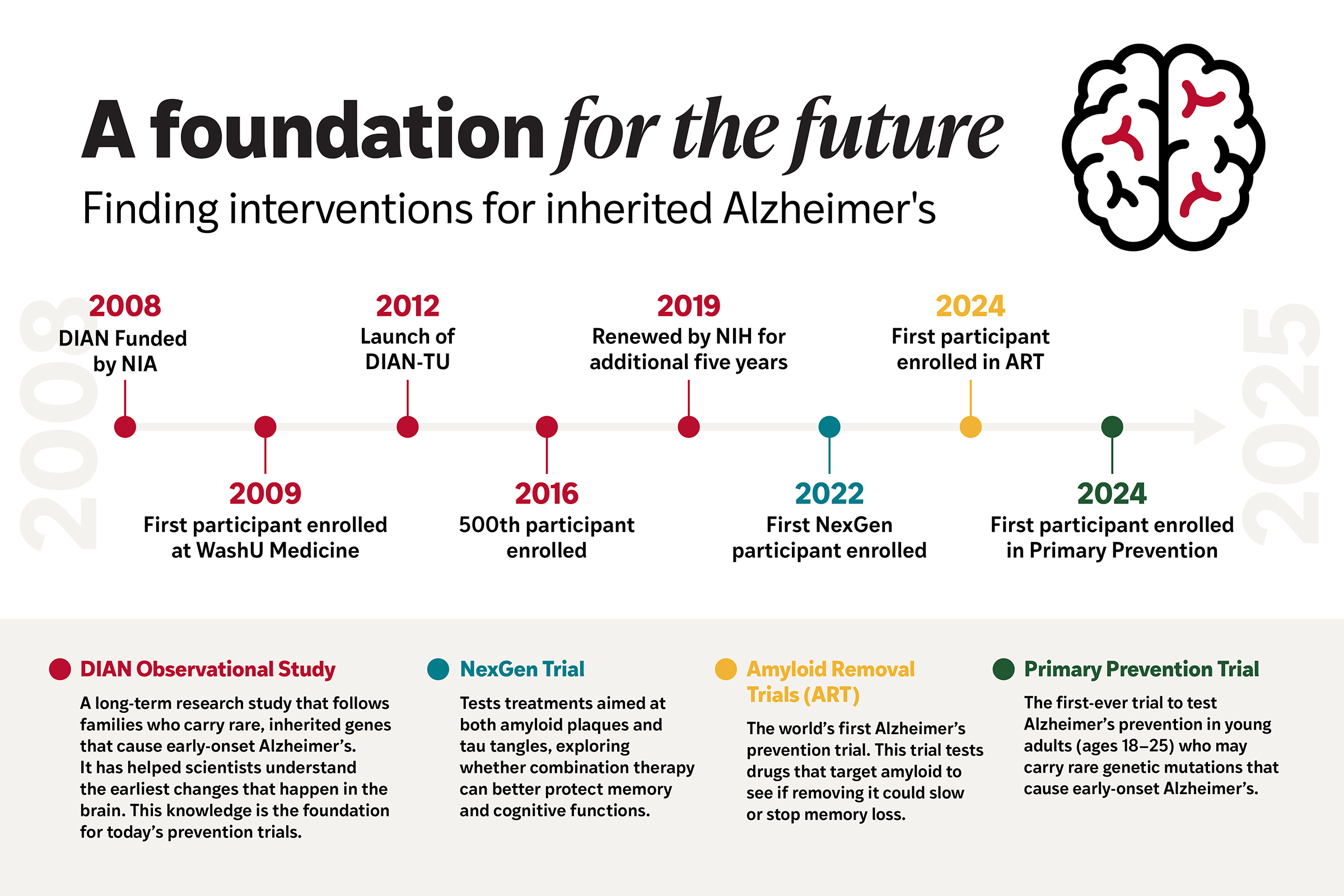

Today’s fight against Alzheimer’s at WashU Medicine began with a bold idea: study the families for whom the disease is an almost certain inheritance. In 2008, Bateman and colleagues launched the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN), an international observational study that brings together families across the world carrying genetic mutations that virtually guarantee early-onset Alzheimer’s.

By carefully tracking changes in the brain and body over time, DIAN revealed something that dramatically changed the field: Alzheimer’s begins long before memory fades. Amyloid plaques start building up 10 to 20 years before symptoms emerge. This finding transformed how scientists thought about the disease. For the first time, there was a roadmap — and a window of opportunity to intervene before it was too late.

That discovery laid the foundation for the DIAN Trials Unit, which launched in 2012 as the world’s first Alzheimer’s prevention trial. Instead of testing one drug at a time, Bateman’s team designed a trial that could test multiple amyloid-targeting therapies in parallel. It was an audacious step, rooted in the belief that stopping Alzheimer’s meant acting earlier — long before families saw the first signs of decline.

Families on the frontlines of research

For Jake Heinrichs, Alzheimer’s is not just a research subject — it is family history written in their DNA. Jake, who is 51, was just 13 when he lost his father, who was in his early 50s. His brother David was 50 when he passed away in 2019. Each carried a rare genetic mutation that guarantees the disease will appear, often decades earlier than typical Alzheimer’s.

Rather than hide from this reality, Jake stepped into the lab without hesitation. In 2012, he volunteered for the DIAN Observational Trial, one of the world’s first prevention trials, led by Bateman’s team. At the time, he didn’t know if he carried the mutation — or if he was receiving the drug or a placebo. “Considering the family history, I was just open to whatever we could do to help out with the research,” Jake recalls. Eventually Jake did receive the drug, and in 2020 genetic testing revealed he had the mutation. But despite the devastating news, the results of his ongoing participation in the trials revealed something extraordinary: while cognition remained stable, biomarkers showed the drug was slowing the biological march of Alzheimer’s. “To have such positive indicators at this moment is life-changing for me,” Jake says.

Jake’s wife Rachel recognized the sacrifice the family has made, and the progress in the understanding of Alzheimer’s it has led to: “The Heinrichs have been giving their blood, their time, their bodies for research their whole lives. It was never a question. It was always about making the world a little better for the next generation.”

Lessons that changed the field

The research results marked a turning point. One of the antibody therapies successfully cleared amyloid plaques from the brain and shifted biological markers tied to Alzheimer’s. Even more compelling, participants who received the therapy had about a 50% lower risk of developing dementia symptoms compared with those who did not. For families who have lived under the weight of inevitability, this was the first real proof that prevention was possible.

Those lessons have reshaped the future of Alzheimer’s research. The next wave of studies at WashU Medicine is combining drugs that remove amyloid with therapies designed to target tau tangles — attacking both culprits behind the disease. And the most ambitious trial yet is underway: a primary prevention study that treats people before plaques appear at all. The hope is profound — if plaques and tangles never form, Alzheimer’s itself may never take root.

“We need to continue to develop and accelerate new preventions for the disease. We can’t wait another 10 years. There are millions of people with the disease today, and there will be more millions more who will get it unless we can discover, validate and implement preventions.” For Bateman, the purpose is clear. “These family members are heroic in ways that we typically only see in the movies and books. With their help, not only is preventing Alzheimer’s and dementia possible — I think it’s probable. As long as we continue to invest the resources necessary.”

From despair to determination

Mary Salter, Carrie’s mother, remembers a time when there was only silence and stigma. “Back in the 1950s, they thought my husband’s mother was just mentally defective. Her records were sealed. No one talked about it,” she says. “When we found out about WashU Medicine, they became our second home. They gave us answers, and they gave us hope.”

That hope is spreading. Across generations, families who once feared their futures now see possibility. Hannah frames it simply: “I want to be the kind of person who can help people like my mom. Research is the one hope that people have. That someday it can change everything. That it can change the course of a family’s life.”

Hope on the horizon

Alzheimer’s still robs too many lives. But in St. Louis, within the labs and clinics of WashU Medicine, there is a new narrative emerging. One not of inevitability, but of intervention. One where science and family courage collide to rewrite the story of neurodegeneration.

“We’ve always dedicated ourselves to any research we could do,” Jake says. “And these studies — this drug — may be saving my life, and my family’s life.”

So, if research takes a long time, even if it’s a lifetime — my lifetime — if it works, in the end, it’s worth it.

— Jake Heinrichs

For Jake, Carrie, Hannah and millions of others, the fight is personal. For Bateman and WashU Medicine, it’s a mission: to transform Alzheimer’s from a death sentence into a solvable challenge.

“Now there’s hope,” adds Jake. “All of a sudden, for the first time in history, there’s a chance that history can change.”

Back to Impact — Neurosciences