$5 million for brain development and Alzheimer’s degeneration study

NIH grant will fund neuroimaging research on mirroring between early brain growth and old age

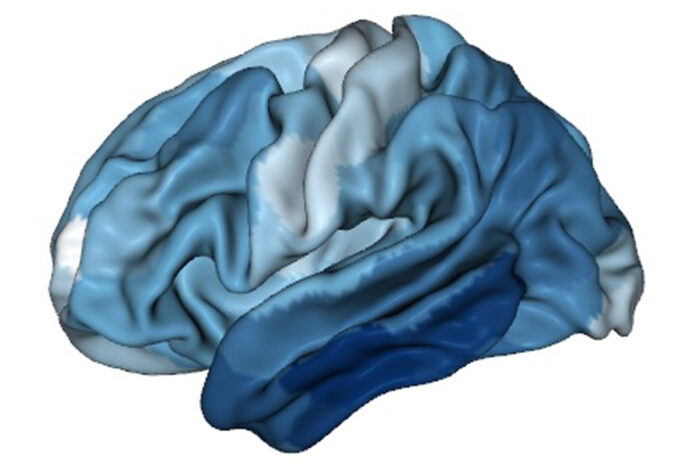

Ty To, courtesy Brian Gordon and Muriah Wheelock

Ty To, courtesy Brian Gordon and Muriah WheelockWashU Medicine Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology researchers have received a grant for $5 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to examine how the pattern of aging and degeneration in the brain mirrors early-life experiences.

A pair of researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has been awarded a $5 million, five-year grant from the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to examine how early-life stress on the developing brain can influence brain aging and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Adverse circumstances in the first years of life — such as low birth weight, poverty, unsafe living conditions and exposure to trauma — are known to alter the development of certain brain regions in ways that are visible on MRI scans and that persist well into early adulthood. These regions, which govern complex functions such as decision-making, language, emotional regulation and memory, are the same ones that take longer to develop than other brain regions and that tend to be affected by Alzheimer’s and other age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Researchers have dubbed this phenomenon “last in, first out,” meaning that the brain regions that develop last are the first to be affected by disease in old age.

Muriah D. Wheelock, PhD, an assistant professor of radiology at WashU Medicine Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR), is a co-principal investigator on the grant with Brian A. Gordon, PhD, an associate professor at MIR. Wheelock said that there was a longstanding theory in the neuroscience community that there was mirroring between neurological development and neurological degeneration. The idea that the areas of the brain that mature last are the first to degrade had not been scientifically quantified, in part because of the computational complexities that the work would require.

Furthermore, longitudinal studies of early-life adversity and health tend to follow participants only into young adulthood. This means that data connecting detrimental brain changes in infants and toddlers to neurodegeneration in old age are lacking.

To fill the gap, Wheelock and Gordon will analyze brain images and other data from large cohorts of individuals across the lifespan to understand how neurodevelopmental changes in the brain’s functional connectivity (the patterns in how different brain regions speak to one another to complete tasks) caused by early-life adversity may prime the brain for specific patterns of degeneration later.

“Damage to these later developing regions could be on a lifelong trajectory that can show up later in life as Alzheimer’s disease or other conditions,” said Wheelock. “We might be able to identify early-childhood or even maternal interventions to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and other age-related neurological disorders.”

Identifying opportunities to change the degeneration trajectory

Wheelock noted that the idea to bridge the data gap between neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration was born out of the uniquely collaborative culture at WashU Medicine.

“Part of the reason this is an unknown area is that it is very technically complex to analyze brain imaging data from both very young and late-life patients, and also because the neurodevelopment and Alzheimer’s research communities don’t usually have the opportunity to communicate with each other,” said Wheelock.

That is not the case at WashU Medicine, where strong communities in both neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration are in frequent contact, according to Gordon. Part of the impetus behind the collaboration between Gordon and Wheelock came from a departmental poster session, where a postdoctoral researcher in Gordon’s lab presented a map showing which regions of the brain communicate most with each other in Alzheimer’s disease.

“One row over, a graduate student from a developmental lab was showing a poster that had a map very similar to our Alzheimer’s image,” said Gordon. “My first thought was that she was conducting aging research, but it turned out her poster was on neurodevelopment.”

That fortuitous encounter led to conversations and eventually collaboration between Wheelock and Gordon — who both lead labs in MIR’s Neuroimaging Labs Research Center — that led to the NIH grant. Over the next five years, their labs will analyze thousands of MRI scans, patient histories and biomarkers from large cohorts representing both ends of the human lifespan, drawn from databases collected at WashU Medicine and other institutions around the world. With that information, they aim to characterize the overlap between early-life development patterns and later-life degeneration, track how adverse social factors and genetic risk factors affect those patterns, and explore the underlying mechanisms of aging and disease progression.

One goal is to identify early-life interventions to mitigate the social stressors tied to neurodegeneration later in life and thereby minimize their influence on age-related diseases.

“The brain is much more plastic in that zero-to-two age range, so any intervention is magnified relative to any other point in life,” said Gordon. “It’s still speculative that we could prevent or reduce Alzheimer’s disease with environmental changes in childhood, but we’re hoping to at least start that discussion.”