$5 million funds innovation of more-potent opioid overdose antidote

NIH funding aims to accelerate drug development timeline for enhanced version of naloxone

Getty Images

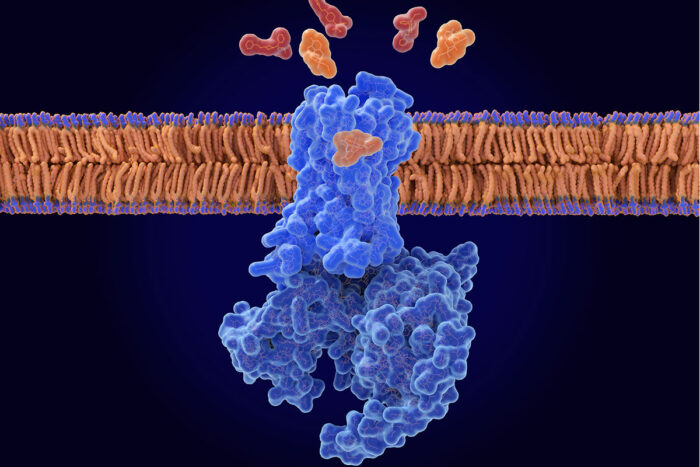

Getty ImagesResearchers at WashU Medicine have received $5 million from the NIH to develop a combination treatment that makes naloxone more effective at counteracting a drug overdose. The illustration shows naloxone (orange) displacing opioids (red) from the opioid receptor (blue) in a nerve cell membrane.

The opioid epidemic claims more than 50,000 lives annually in the U.S., highlighting the urgent need for lifesaving interventions. Although naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan, effectively restores normal breathing during an overdose, its effects are short-lived and often require multiple doses. Meanwhile, emerging, more dangerous opioids threaten naloxone’s lifesaving effectiveness.

A team of researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Stanford University and the University of Florida had previously identified a compound that makes naloxone more potent and longer lasting without worsening withdrawal symptoms. Now, with a $5.2 million grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the researchers aim to develop the newly identified compound into a drug by combining it with naloxone into a single formulation that can be tested in future clinical trials.

“As new, more-potent opioids take to the streets, reviving people from overdose is becoming more challenging,” said Susruta Majumdar, PhD, a professor of anesthesiology at WashU Medicine and the principal investigator on the new project. “To get ahead of these dangerous opioids, we urgently need more powerful antidotes. This funding support from NIH is critical for expediting the drug development timeline, making it possible to bring new treatments to people within five years.”

A better naloxone

Opioids such as oxycodone and fentanyl bind to a pocket on the opioid receptor, a receptor found primarily on neurons in the brain. The binding triggers a cascade of events that reduce pain perception, induce a sense of euphoria and slow down or, in the case of an overdose, stop breathing. Naloxone — available as an over-the-counter nasal spray or injectable — is an opioid, but unlike other drugs in its class, it doesn’t activate the opioid receptor when it slips inside its binding pocket. By displacing problematic opioids from the pocket, naloxone can restore normal breathing to reverse an overdose. But naloxone has a shorter half-life than other opioids, such as fentanyl, so it wears off sooner. This means any circulating fentanyl molecules can re-attach to and re-activate the receptor, causing the overdose symptoms to return.

The research team — led by Majumdar; Brian K. Kobilka, PhD, a professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford University; and Jay P. McLaughlin, PhD, a professor of cellular and systems pharmacology at the University of Florida College of Pharmacy — previously found a molecule that keeps naloxone in the binding pocket longer, strengthening its ability to reverse an opioid overdose.

In a study published in 2024 in Nature, the researchers determined that in the presence of the new molecule, which they dubbed compound 368, naloxone stayed in the binding pocket at least 10 times longer than without the compound in experiments performed in cells. As a negative allosteric modulator (NAM) of the opioid receptor, compound 368 adjusts the body’s response to drugs that bind to the opioid receptor by fine-tuning the activity of drug receptors. The researchers also found that the addition of the compound boosted naloxone’s potency without worsening withdrawal symptoms in mice exposed to opioids. Such symptoms, including pain, chills, vomiting and irritability, can be so severe that people resume opioid use to alleviate them, perpetuating the cycle of addiction.

With the new funding, the researchers aim to develop a naloxone-enhancing 368 compound that can be administered intranasally or intravenously with naloxone. Their work will focus on improving the compound’s solubility and size to ensure it dissolves properly in the bloodstream and can reach the brain effectively. After optimizing the compound’s drug-like properties, they will test in mice if it enhances naloxone’s ability to counteract opioid overdoses without worsening withdrawal symptoms, paving the way for future testing in clinical trials.

“Such funding from the NIH is critical for accelerating the transition of discoveries like ours from the lab to clinical use,” said Majumdar, who is a member of the Center for Clinical Pharmacology in the Department of Anesthesiology. “We are motivated to work exceptionally fast due to the speed with which opioids get stronger and more dangerous.”