$5 million supports innovative breast cancer trial

Research aims to improve therapies for hard-to-treat tumors

Matt Miller

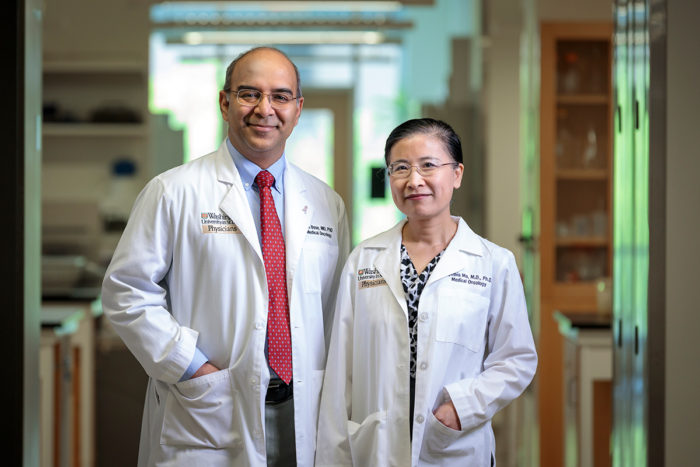

Matt MillerRon Bose, MD, PhD, (left) and Cynthia Ma, MD, PhD, and their teams are conducting research that may lead to better therapies for some breast cancer patients. They have been awarded a $5 million grant to support such research.

A $5 million grant from the Department of Defense will support research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis aimed at improving breast cancer therapies. The research focuses on HER2-positive breast cancer. Such tumors are dotted with an overabundance of so-called HER2 receptors.

About 20 percent of women with breast cancer have HER2-positive tumors. Drugs that block HER2, such as Herceptin, have improved survival rates dramatically for these patients.

But these drugs’ use has been limited to patients who have too many copies of HER2. Recent studies led by Washington University researchers, however, have shown that other breast cancer patients with different HER2 defects may benefit from HER2 inhibitors. In these patients, mutations in HER2 can fuel cancer growth. Standard testing for HER2 positive breast cancer won’t identify patients with HER2 mutations.

“We’re figuring out how to treat breast cancer based on the mutations present in the specific patient’s tumor,” said co-principal investigator Ron Bose, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine. “We’ve developed a diagnostic test for mutations in HER2 that cause overactive signaling, and we have a good drug for patients with these mutations in their tumors. These new diagnostic and therapeutic tools may let us identify more women with HER2-driven cancers and treat them with HER2 inhibitors.”

Based on data from 2017, Bose and his colleagues estimate that about 4,000 women have metastatic breast cancer with HER2 mutations and could potentially benefit from this strategy. Drug combinations targeting tumor proteins are generally less toxic than standard chemotherapy, which is not very effective in controlling metastatic cancer and is the only current treatment option for these patients.

The grant will support a clinical trial at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine investigating a HER2 blocker called neratinib. Trial participants will be patients with metastatic breast tumors that have HER2 mutations and are estrogen-receptor positive, meaning these tumors also are fueled by estrogen. Because these tumors are fed by two fuel sources, participants will receive neratinib to block HER2 and fulvestrant to attack the estrogen receptor.

“In a past clinical trial, we tested neratinib alone, and we saw that about 30 percent of patients had a positive therapeutic benefit from the drug,” said co-principle investigator Cynthia X. Ma, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine. “Now, we want to see whether adding fulvestrant will improve that outcome and help more patients.”

To more fully understand how patients respond to the drugs, the researchers will implant the patients’ tumors into mice that then will receive the same treatment regimens. Additional drugs also will be tested in these mouse models to see if other treatment combinations suggest promising directions for future clinical trials.

The mouse models will provide insight into why some tumors become resistant to neratinib therapy. The scientists will perform genome sequencing and protein analysis on these tumors, seeking clues to how some of them develop the ability to evade drugs that had been lethal to them initially.

Collaborating sites for the clinical trial include Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Harvard Medical School and Baylor College of Medicine.