Alzheimer’s missing link ID’d, answering what tips brain’s decline

Brain’s immune cells form nexus between two damaging Alzheimer’s proteins

Cheryl Leyns and Maud Gratuze

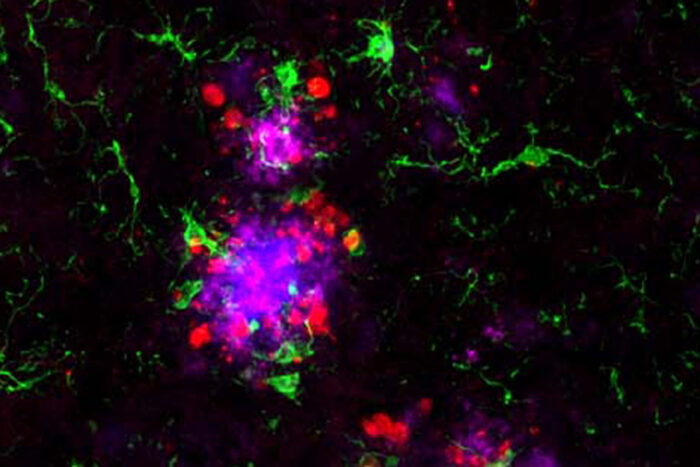

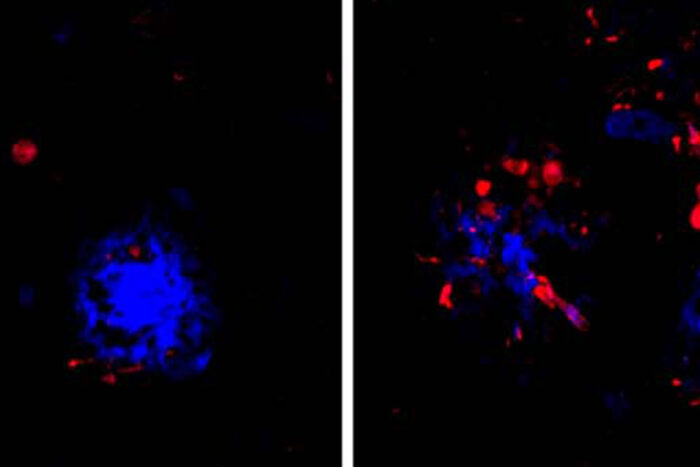

Cheryl Leyns and Maud GratuzeIn Alzheimer’s, amyloid clumps (blue) develop first in the brain, followed by tangles of the protein tau (red). Tau is associated with memory loss and confusion. People with a genetic variant that hobbles immune cells in their brains (image at right) accumulate more tau near amyloid plaques than people with fully functional immune cells (left). Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that immune cells that typically protect neurons from damage may be the link between such early and late brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Breaking that link could lead to new approaches to delay or prevent the disease.

Years before symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease appear, two kinds of damaging proteins silently collect in the brain: amyloid beta and tau. Clumps of amyloid accumulate first, but tau is particularly noxious. Wherever tangles of the tau protein appear, brain tissue dies, triggering the confusion and memory loss that are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that the link between the two proteins may lie in the brain’s immune cells that hem in clumps of amyloid. If the immune cells falter, amyloid clumps, or plaques, injure nearby neurons and create a toxic environment that accelerates the formation and spread of tau tangles, they report.

The findings, in mice and in people, are published June 24 in Nature Neuroscience. They suggest that reinforcing the activity of such immune cells – known as microglia – could slow or stop the proliferation of tau tangles, and potentially delay or prevent Alzheimer’s dementia.

“I think we’ve found a potential link between amyloid and tau that people have been looking for for a long time,” said senior author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology. “If you could break that link in people who have amyloid deposition but are still cognitively healthy, you might be able to stop disease progression before people develop problems with thinking and memory.”

While the formation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles have been recognized as key steps in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, researchers have struggled to pin down the relationship between the two. By themselves, amyloid plaques do not cause dementia. Many people over age 70 have some amyloid plaques in their brains, including some who are as mentally sharp as ever. But the presence of amyloid plaques seems to lead inexorably to the formation of tau tangles – the true villain of Alzheimer’s – and, until now, it wasn’t clear how amyloid drives tau pathology.

Holtzman and colleagues – including first authors Cheryl Leyns, PhD, a former graduate student in Holtzman’s lab, and Maud Gratuze, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher, as well as co-senior author Jason Ulrich, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology – suspected that microglia could be the link. A rare mutation in a gene called TREM2 leaves people with weak and ineffective microglia, and also increases their risk of developing Alzheimer’s by twofold to fourfold.

As part of the study, the researchers used mice prone to developing amyloid plaques and modified in various ways their TREM2 genes to influence the activity of their microglia. The result was four groups of mice: two with fully functional microglia because they carried the common variant of either the human or mouse TREM2 gene, and two with impaired microglia that carried the high-risk human TREM2 variant or no copy of the TREM2 gene at all.

Then, the researchers seeded the mice’s brains with small amounts of tau collected from Alzheimer’s patients. The human tau protein triggered the tau in mice to coalesce into tangle-like structures around the amyloid plaques.

In mice with weakened microglia, more tau tangle-like structures formed near the amyloid plaques than in mice with functional microglia. Further experiments showed that microglia normally form a cap over amyloid plaques that limits their toxicity to nearby neurons. When the microglia fail to do their job, neurons sustain more damage, creating an environment that fosters the formation of tau tangle-like lesions.

Further, the researchers also showed that people with TREM2 mutations who died with Alzheimer’s disease had more tau tangle-like structures near their amyloid plaques than people who died with Alzheimer’s but did not carry the mutation.

“Even though we were looking at the brains of people at the end of the Alzheimer’s process rather than the beginning, as in the mice, we saw the same kind of changes: more tau in the vicinity of amyloid plaques,” Holtzman said. “I’d speculate that in people with TREM2 mutations, tau accumulates and then spreads faster, and these patients develop problems with memory loss and thinking more quickly because they have more of those initial tau tangles.”

The converse also may be true, Holtzman said. Powering up microglia might slow the spread of tau tangles and forestall cognitive decline. Drugs that enhance the activity of microglia by activating TREM2 already are in the pipeline. It soon may be possible to identify using a simple blood test people with amyloid buildup but, as yet, no cognitive symptoms. For such people, drugs that break the link between amyloid and tau might have the potential to halt the disease in its tracks.