Alzheimer’s risk linked to energy shortage in brain’s immune cells

Energizing the cells in mice limits damage to neurons

Tyler Ulland

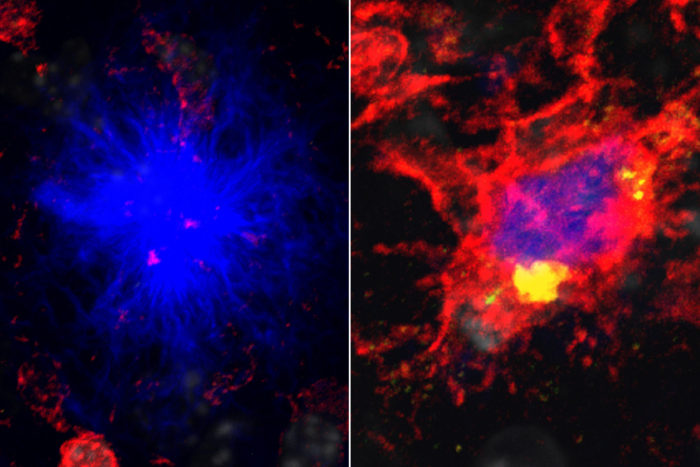

Tyler UllandA new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that mutations in the gene TREM2 cause an energy shortage in the brain's immune cells (red), leading to their failure to protect neurons from damaging clumps of protein (blue). On the left, immune cells fail to protect neurons against the protein. On the right, immune cells given a supplemental source of energy succeed in protecting against the protein by surrounding it.

People with specific mutations in the gene TREM2 are three times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than those who carry more common variants of the gene. But until now, scientists had no explanation for the link.

New research in mice at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that the high-risk mutations in TREM2 cause an energy deficit in cells that clear away debris in the brain. When such cells are running on empty, they can’t protect neurons from harmful plaques that tend to collect in the brain as people get older.

“Everybody has some plaques, but the activity of these cells affects how much damage the plaques do,” said senior author Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, Professor of Pathology. “So if you have dysfunction in these cells, you have an accelerated process of neurodegeneration. If the cells are more functional, you can delay the process.”

The findings suggest that energizing the brain’s cleanup crew – made up of a kind of immune cell known as microglia – could reduce neurological damage and forestall the memory loss and confusion experienced by people with Alzheimer’s disease.

The study is published Aug. 10 in the journal Cell.

Amyloid beta is a sticky protein that neurons release as a byproduct of their normal functioning. The protein is harmless if swept away quickly, but when it starts forming plaques it can injure the neurons nearby.

Colonna and colleagues previously had shown that normal microglia surround and wall in the plaques, keeping the area of injury contained. Microglia from mice lacking TREM2, however, allow the plaques to spread and damage neurons more extensively.

To find out why microglia carrying certain TREM2 variants fail to do their job, Colonna, postdoctoral researcher Tyler Ulland, PhD, and MD/PhD student Wilbur Song and their colleagues studied microglia from mice genetically predisposed to develop amyloid plaques and lacking TREM2.

When they viewed the microglia under a microscope, they saw that the microglia were digesting and recycling their own proteins, a sign that their energy stores were running low.

With the aid of David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology, the researchers also looked at microglia from people who had died of Alzheimer’s disease and carried high-risk TREM2 mutations. These cells, too, had been eating their own proteins.

If TREM2 deficiency led to an energy shortage, the researchers reasoned, then providing the microglia with a source of extra energy might restore their ability to do their job. The researchers gave mouse microglia an energy-rich compound called cyclocreatine, and the microglia once again surrounded amyloid plaques.

To find out whether the compound could reduce damage to a living brain, the researchers fed cyclocreatine or a placebo for six months to mice lacking TREM2. In the brains of mice fed cyclocreatine, microglia surrounded the plaques and neurons showed significantly less damage.

“If you supplement the microglial metabolic capacity, you can reduce a lot of the damage,” Ulland said. “What this shows is that microglia need to be on their game to deal with the threats to the neurons.”

Cyclocreatine and its cousin creatine are sold as dietary supplements to build muscle. However, the compounds have been linked to heart disease, kidney disease and metabolic problems. The researchers have begun evaluating other compounds that can support energy metabolism without the dangerous side effects of cyclocreatine.

“We strongly advise against going to the store and buying up cyclocreatine for your parents or grandparents,” said Colonna, who is also a professor of medicine. “Taking cyclocreatine, especially for a long time, carries real and serious risks.”

TREM2 is one of about a dozen genes related to microglial function and that raise the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, suggesting that fully functional microglia play an important role in the brain’s defenses against the disease.

“We’re trying to find out now if it is possible to hyperactivate microglia so they have better-than-normal function,” Colonna said. “If you can only restore normal function, then microglial treatments will be only useful for people who have microglial deficiency. But if you can hyperactivate the microglia, then this therapy could be useful for everybody. It’s an intriguing possibility.”