Arthritis-causing virus hides in body for months after infection

Researchers develop way to ID cells infected with chikungunya

Alissa Young and Marissa Locke

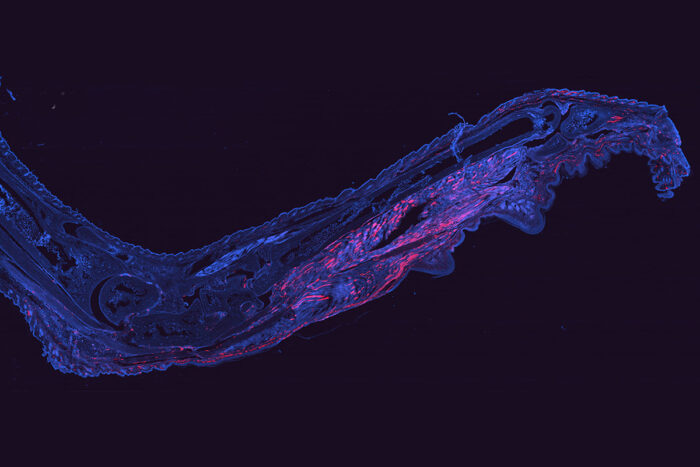

Alissa Young and Marissa LockeCells harboring chikungunya virus (red) are visible in a mouse foot 28 days after infection. The virus is notorious for causing prolonged, painful arthritis that can last for years. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a way to fluorescently tag cells infected with chikungunya virus. The technique opens up new avenues to study how the virus persists in the body and potentially could lead to a treatment.

Since chikungunya virus emerged in the Americas in 2013, it has infected millions of people, causing fever, headache, rash, and muscle and joint pain. For some people, painful, debilitating arthritis lasts long after the other symptoms have resolved. Researchers have suspected that the virus or its genetic material – in this case, RNA – persist in the body undetected, but they have been unable to find its hiding places.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have figured out a way to detect cells infected with chikungunya virus that survive the infection. They genetically modified the virus such that it activated a fluorescent tag within cells during infection. Months after the initial infection, the researchers could detect glowing red cells still harboring viral RNA.

The study, in mice, opens up new ways to understand the cause of – and find therapies for – chronic viral arthritis.

The findings are published Aug. 29 in PLOS Pathogens.

Senior author Deborah Lenschow, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine and of pathology and immunology, and co-first author and graduate student Marissa Locke answered questions about the research, which was conducted in collaboration with co-first author Alissa Young, PhD, co-author Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine, and others.

How common is chronic arthritis caused by chikungunya infection?

Lenschow: Between 30% and 60% of people infected with chikungunya virus go on to develop chronic arthritis that can last up to three or four years after infection. Researchers had found viral RNA in joint fluid from people with chronic arthritis, but they didn’t know whether the virus had gone dormant or whether it was still multiplying and infecting new cells at an undetectably low level.

Locke: Nobody had located the cells that harbored the viral RNA. This matters because if we can’t find the infected cells, we can’t study them.

Where did you find the virus, and what does that tell you about the cause of chronic arthritis?

Locke: We found the virus in muscle cells and in connective tissue cells in the skin and muscle. These cells likely had become infected within the first week of the virus invading the body, yet managed to survive. They were still there in the muscles and joints up to 114 days after infection, and they still had viral RNA inside them.

Lenschow: One hypothesis would be that the viral RNA that’s persisting in the cells is triggering chronic inflammation, and that is what contributes to the symptoms of arthritis. For reasons that we don’t understand, inflammation fails to get rid of the viral RNA, or at least not quickly.

What impact will the development of this new tagging technique have on people suffering from chronic viral arthritis?

Lenschow: We’re a long way from having a treatment to offer people. But the first step to developing a therapy is understanding the cause of the symptoms, and this technique helps us accomplish that. If we understand the cause, that could hopefully lead us to identify therapeutic interventions to help alleviate some of the chronic symptoms.

Locke: We can use this approach to find out what’s driving the chronic inflammation and how to resolve it. We can study which proteins or other components of the immune response worsen or alleviate the inflammation, and what happens to the infected cells when we turn those components up or down.