Beneficial role clarified for brain protein associated with mad cow disease

Protein helps maintain nerve function over lifespan

Amit Mogha

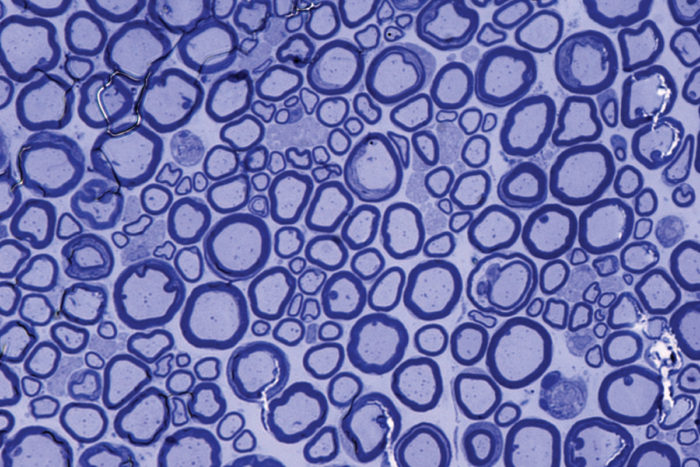

Amit MoghaA new study clarifies the normal role of a protein typically associated with fatal prion diseases. Cross-sections of healthy nerve axons, pictured, show a thick layer of myelin, the insulation that speeds the propagation of electrical signals through the nervous system's wiring. When properly folded, prion proteins play a vital role in maintaining this insulating layer of myelin.

Scientists have clarified details in understanding the beneficial function of a type of protein normally associated with prion diseases of the brain, such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly known as mad cow disease) and its human counterpart, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Studying mice and zebrafish, researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Zurich have shown that the proteins — when properly folded — play a vital role in nerve cell function by maintaining the insulation around axons, the nervous system’s electrical “wiring.”

The study appears August 8 in the journal Nature.

Improperly formed prion proteins that cause disease are infectious because they hijack their neighbors, resulting in misfolded proteins and setting off a domino effect that spreads through the brain destroying tissue. Although the role of prion proteins in these fatal brain diseases is well-known, scientists have long puzzled over the normal function of the protein, called PrPC.

“Previous studies have suggested a role for prion proteins in maintaining neurons, but until now, no one knew how the properly folded versions of the proteins function,” said co-author Kelly R. Monk, PhD, an associate professor of developmental biology at Washington University. “It’s surprising to see that the protein has a role in maintaining the structure of nerve cells, considering that a misfolded version of PrPC is known to cause fatal brain diseases.”

Past work by the researchers at the University of Zurich demonstrated that mice lacking PrPC had disruptions in the insulation surrounding axons, but the reasons for the disruptions were unclear. The new study demonstrates that PrPC binds to Schwann cells, which are cells that provide support for the brain’s neurons. Schwann cells produce the nerve-insulating protein called myelin and then wrap this insulation around the long, thin axons. Properly insulated axons enable the rapid propagation of nerve signals. Specifically, PrPC binds to a docking site on Schwann cells called Gpr126.

In past work, Monk and her Washington University colleagues demonstrated that the docking site on cells played an important role in nerve formation during embryonic development in zebrafish and in mice. But the new study identifies roles for both Gpr126 and PrPC in maintaining the integrity of neurons through adulthood.

When either of these components is missing, Monk said mice experience a gradual loss of interactions between Schwann cells and axons, with a resulting loss of of myelin. Without this important insulation, walking progressively becomes more difficult for mice, and they eventually reach a state of paralysis.

“We have identified a definitive function for the normal prion protein and clarified how it works on a molecular level,” said senior author Adriano Aguzzi, MD, PhD, of the University of Zurich. “Our study answers a question that has been intensely researched since the prion gene’s discovery in 1985.”

The researchers said the findings may have implications for understanding and eventually treating nerve disorders that result from the loss of the insulating myelin sheaths, such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and other devastating peripheral neuropathies.