Beverley named Ernest St. John Simms Distinguished Professor

Honored for studies of the tropical parasite Leishmania

Mark Beaven

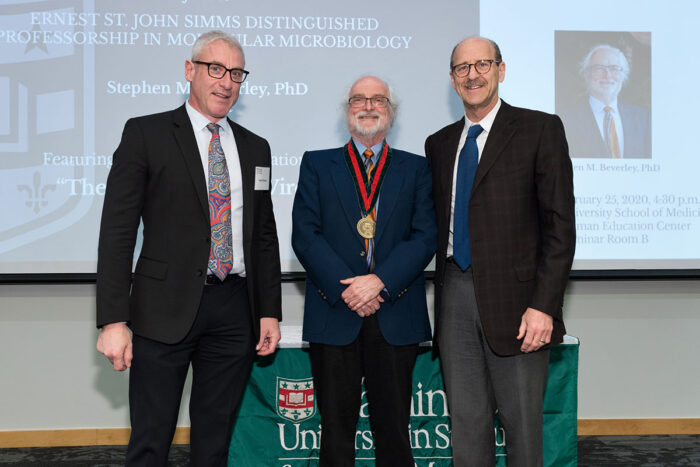

Mark BeavenAt the installation of Stephen Beverley, PhD, as the inaugural Ernest St. John Simms Distinguished Professor of Molecular Microbiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are (from left) Sean Whelan, PhD, head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology; Beverley; and David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

Stephen Beverley, PhD, who helped identify novel drug and vaccine candidates for potentially lethal infections caused by the parasite Leishmania, has been named the inaugural Ernest St. John Simms Distinguished Professor of Molecular Microbiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The professorship was endowed by the Department of Molecular Microbiology in honor of Simms, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology who died in 1983.

“I am pleased to recognize the accomplishments of both Professor Simms and Professor Beverley with this endowed professorship,” said Chancellor Andrew D. Martin. “Professor Simms was a trailblazer who made foundational contributions to two fields of biology – genetics and immunology – during his decades at the School of Medicine. He also provided encouragement and inspiration, particularly to African American students, faculty and staff as the first African American to hold a full-time academic appointment at the School of Medicine. We honor his legacy by awarding this endowed professorship to Dr. Beverley, who combines leadership with scientific accomplishment, much like Professor Simms.”

Beverley is a leading expert on Leishmania, single-celled parasites that cause infections of the skin and internal organs and are spread by sand flies in the tropics and subtropics. These infections can be disfiguring and sometimes deadly. Beverley developed the first genetic tools for protozoan parasites. Such tools help researchers identify and investigate the genetic factors that allow parasites to survive in the body, evade the immune response and cause illness. Beverley’s groundbreaking work with a virus that infects Leishmania has led to new strategies to reduce the severity of disease and improve the success of treatment regimens by targeting the virus within the parasite.

“Steve Beverley is a superb scientist whose seminal contributions have changed the way research is conducted on Leishmania and other protozoan parasites,” Perlmutter said. “In addition, he helped build a strong molecular microbiology program that put the School of Medicine at the forefront of research into emerging infectious diseases.”

Beverley led the Department of Molecular Microbiology from 1997 to 2018. During that time, he more than doubled the size of the department. He spearheaded efforts to reach out to infectious disease researchers in other departments at the School of Medicine and facilitate opportunities to collaborate.

“A leader in parasitology, Steve Beverley pioneered molecular genetic approaches to understanding Leishmania that have laid the foundation to advance counter measures against this understudied infection,” said Sean Whelan, PhD, the newly named Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor and head of Molecular Microbiology. “At the helm of the molecular microbiology department, he built a thriving, diverse community of investigators with common interests in understanding how microbes cause disease, and worked tirelessly to strengthen the broader microbial sciences community. It is an honor to succeed him.”

Beverley earned a PhD in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, before completing postdoctoral research at Stanford University. In 1997, he joined the faculty at the School of Medicine as head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology. He is a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences and of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. In 2017, he received the Peter H. Raven Lifetime Achievement Award from the St. Louis Academy of Science.

Simms came to the School of Medicine in 1936 at the age of 19 as a technician in the Department of Surgery. From north St. Louis, Simms had completed two years of college at the University of Minnesota and dreamed of becoming an engineer, but his father’s death forced him to drop out and return home to help support his family. He never completed his degree.

Apart from a few years in the 1940s, Simms spent his career at the School of Medicine. In 1953, he joined a group led by Arthur Kornberg, MD, in the Department of Microbiology. Simms was an author on influential papers detailing how genetic information is duplicated and then passed on to the next generation. The importance of the research was recognized by the Nobel Committee in 1959, when they awarded Kornberg and Severo Ochoa, MD, a Nobel Prize for the discovery of the mechanisms responsible for the synthesis of DNA and RNA.

When Kornberg moved his lab to Stanford University, Simms chose to remain in St. Louis and took a position with Herman Eisen, MD, the head of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. There, he contributed to studies of how an individual’s immune system recognizes and reacts against virtually limitless numbers of different foreign substances called antigens. His work helped lay the foundations of modern immunology.

Simms was also a leader outside the laboratory. During World War II, he worked at a small-arms plant making bullets for the war effort. There, he led a successful strike for better working conditions for his fellow African Americans. At the School of Medicine, he trained a generation of scientists and served on the admissions committee, where he advocated for minority applicants.

“Ernie Simms was a beloved teacher and brilliant scientist,” Beverley said. “Although I never met him, he had a reputation for holding his colleagues to the highest scientific standards, but in a way that was always kindly and tactful. The Department of Molecular Microbiology established this professorship in recognition of Simms’ spirit of scientific excellence and commitment to training the next generation.”

In 1968, the School of Medicine recognized Simms’ talents and accomplishments by promoting him to research assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. In light of his outstanding contributions across two fields, the School of Medicine promoted him again in 1972, to associate professor, and awarded him tenure, despite his lack of a college degree. After his death, the School of Medicine established an endowed scholarship in his name that was funded through gifts from his friends, colleagues and students.