Blood marker could help ID those at risk of debilitating peripheral artery disease

Could also lead to earlier diagnosis, improved therapies for cardiovascular disease

Zayed Research Lab

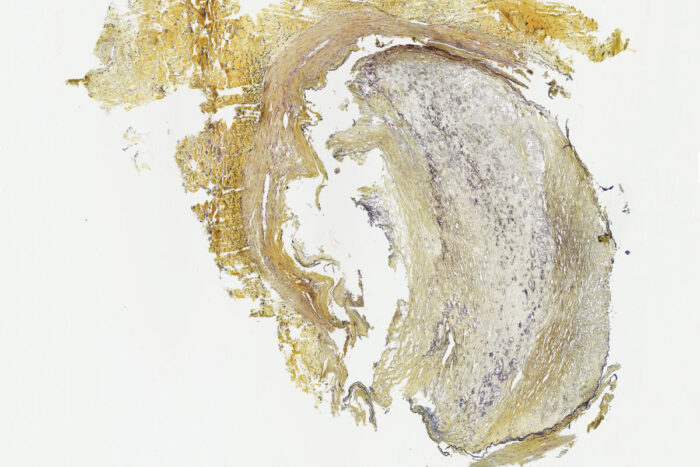

Zayed Research LabPictured is a cross section of a peripheral artery from the leg of a patient with chronic limb-threatening ischemia, a condition in which heavy plaque formation causes a severe narrowing of the arteries. A new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has identified a key protein in the blood that could be measured to identify such patients earlier in the disease process, so they can be treated more quickly and avoid severe forms of the condition.

To track cardiovascular health, doctors measure blood pressure, cholesterol levels and blood sugar, among a number of other cardiovascular disease risk factors. Such measures can help predict whether a person is at risk of heart attack or stroke. But there is no blood test that can accurately assess the degree to which a person’s arteries may be narrowing or at risk of blockage.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that high levels of a specific protein circulating in the blood accurately detect a severe type of peripheral artery disease that narrows the arteries in the legs and can raise the risk of heart attack and stroke. The protein, called circulating fatty acid synthase (cFAS), is an enzyme that manufactures saturated fatty acids. Until recently, fatty acid synthase was thought to be found only inside cells. The new study suggests that fatty acid synthase also circulates in the bloodstream and may have an important role in the plaque formation characteristic of cardiovascular disease.

The study appears online in the journal Scientific Reports.

About 12 million people in the U.S. have some form of peripheral artery disease, a narrowing of the arteries in the legs, and about 1 million of these patients develop a severe form called chronic limb-threatening ischemia. These patients often undergo vascular surgery to open up their peripheral arteries in an effort to improve blood flow to the legs. In severe cases, patients may need to have the diseased leg amputated.

“These patients are at risk of losing their legs, which is devastating to quality of life,” said senior author Mohamed A. Zayed, MD, PhD, an associate professor of surgery and of radiology. “They lose their capacity to walk, and about half of them die within the next two years. We need to identify these patients sooner, so we can help treat them aggressively much earlier in the disease course. Our data suggest that levels of cFAS in the blood could be an accurate predictor for which patients are at high risk of the severe forms of this condition.”

Zayed and his colleagues collected blood samples from 87 patients before they underwent vascular surgery to treat chronic limb-threatening ischemia. The researchers found that cFAS levels in the blood were independently associated with the disease. A diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes and smoking status also were strongly and independently correlated with chronic limb-threatening ischemia. When all three of these factors were considered together, they could predict the presence of the disease with 83% accuracy.

The researchers also found that cFAS levels in the blood were associated with the fatty acid synthase content of plaque sampled from the femoral artery, the main vessel supplying blood to the legs. In addition, the researchers found that cFAS circulates through the bloodstream while bound to LDL, the so-called “bad” LDL cholesterol, which raises an intriguing question.

“Oftentimes, I will see patients in my practice who have high LDL but are otherwise healthy individuals — they don’t have evidence of disease in their arteries,” said Zayed, who is also a vascular surgeon at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “We’ve scratched our heads at this. Do we put these patients on cholesterol-lowering medication? Are they still at high risk of cardiovascular disease? Our guidelines tell us to be aggressive in treating these patients. But my suspicion is the problem is not just LDL. Rather, the problem is enzymes that are attached to LDL that are conferring the cardiovascular disease that we see, particularly in the peripheral arteries, as well as the coronary arteries that deliver blood to the heart and the carotid arteries that deliver blood to the brain.”

The researchers have found that LDL is more abundant than cFAS in the blood, so the key measure may not be LDL itself, but how much of the LDL is carrying cFAS along with it.

In past work, Zayed and his colleagues showed that blood cFAS levels also are elevated in patients with plaque buildup in the carotid arteries, which supply blood to the brain. That work also showed that the cFAS circulating in the blood originates from the liver. The evidence suggests that LDL serves as a delivery vehicle for cFAS that then contributes to the formation of plaque in key arteries throughout the body.

Zayed and his colleagues also are investigating cFAS as a possible target of new drug therapies that could slow plaque buildup and treat or prevent cardiovascular disease.

“There are drugs that inhibit fatty acid synthase, and we’re working on evaluating new ones that are more targeted,” Zayed said. “None of them are ready for clinical trials in people for this purpose yet, but we’re using those drugs to test animal models of the disease to see if they actually decrease the buildup of plaque in the arteries. It would be wonderful to be able to practice precision vascular medicine — to tailor therapy to high-risk patients to reduce their risk of developing severe complications of cardiovascular disease.”

In the meantime, Zayed is working with Washington University’s Office of Technology Management to develop a test kit for measuring cFAS in the blood so that high-risk patients may be identified earlier.