Book club for medical professionals explores field’s human side

Popular reading group discusses works involving death, PTSD, feminism and other topics

Robert Boston

Robert BostonTimothy Moore, PhD, (left) head of Washington University's Department of Classics in Arts & Sciences, recently moderated a book club discussion among health-care professionals who work on the Medical Campus. Robert M. Feibel, MD, (right) oversees the reading group as the School of Medicine's director of the Center for History of Medicine.

In between appetizers and desserts, the physicians and nurses pondered whether society overmedicalizes basic human conditions — and whether health-care professions in general dismiss an abstract disease of the mind because, unlike a malignant tumor, it cannot be seen or removed.

Also during the meal, participants delved into a discussion on how public dialogue about devastating war experiences focuses almost exclusively on men. Throughout the dinner and over sips of tea and coffee, a passionate analysis ensued over which Greek mythical figures might have suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Every month, these health-care professionals pause from their hectic schedules and bond as bibliophiles during the “Medicine and Literature” reading group sponsored by the university’s Center for History of Medicine and held at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

“The medical book club is an opportunity to step back from the daily whirlwind of seeing patients, struggling with insurance issues and reviewing charts and laboratory reports,” said Robert M. Feibel, MD, the center’s director and a professor of clinical ophthalmology.

The book club is open to physicians and nurses at Washington University School of Medicine, Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis Children’s Hospital and the Goldfarb School of Nursing at Barnes-Jewish College. “It allows participants to reflect on why we do what we do,” Feibel said. “It lets us look at the human side of our work and think about larger themes of medicine beyond our own viewpoints.”

Five fiction and nonfiction books were selected by health-care professionals for this year’s reading group. They are:

- “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End,” by Atul Gawande;

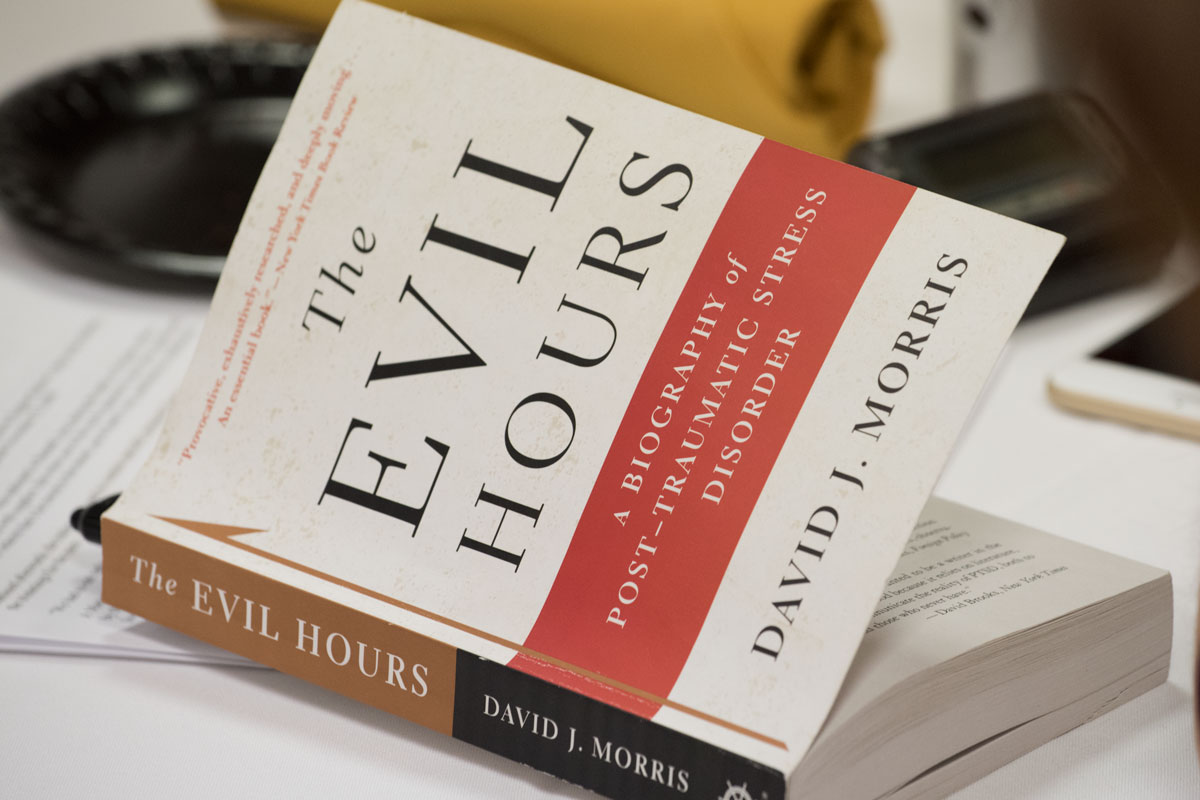

- “The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” by David J. Morris;

- “From Silence to Voice: What Nurses Know and Must Communicate to the Public (The Culture and Politics of Health Care Work),” by Bernice Buresh and Suzanne Gordon;

- “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley;

- “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors and the Collision of Two Cultures,” by Anne Fadiman.

In its second year, the literary group already has a waiting list. “We keep the reading group to 25 people to encourage personal interactions and meaningful discussions,” Feibel said. “We also open it only to faculty, attending physicians and registered nurses since they have many similar experiences.”

The book club is one of several programs affiliated with the Center for History of Medicine. The center offers electives on the history of medicine for first-year medical students, reading electives for fourth-year students, a series of lectures for the campus community and general public, and special programs in the medical humanities field with Danforth faculty.

During a winter meeting, the group discussed the critically acclaimed “The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” by Morris, a journalist and former Marine infantry officer who chronicled the history of PTSD, as well as his experience with the condition.

Leading the talk was guest participant Timothy Moore, PhD, the John and Penelope Biggs Distinguished Professor and chair of Washington University’s Department of Classics in Arts & Sciences on the Danforth Campus. He started the talk with an overview of PTSD, a modern diagnosis that existed long before there was a name for it.

“We can gain insights from figures in ancient Greek literature who appear to suffer from symptoms similar to what we now diagnose as PTSD,” said Moore, who sprinkled references to Greek literary figures throughout the book club meeting. “Ajax, the tragic hero by the Greek playwright Sophocles, tries to kill his leaders in a fit of madness. This action, which has long troubled scholars, can be explained at least partially if we posit that Ajax, like so many modern combat veterans, suffered from PTSD. Similarly, Medea, who kills her children after being jilted by her husband in a tragedy of Sophocles’ contemporary Euripides, has been explained as a woman driven to extremes by PTSD.”

An animated discussion focused on sexual assault and PTSD. “Women have been traumatized forever with sexual assaults,” said Laura Jean Bierut, MD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Psychiatry at Washington University. “Rape is unfortunately common, especially in wartime. I find it fascinating that PTSD is a diagnosis that grew out of men’s issues with trauma and not women’s.”

Robert Boston

Robert BostonIn fact, Bierut said, a PTSD diagnosis in and of itself is intriguing. “Many people have experienced trauma,” she said. “My father was a World War II veteran who saw many men die as he lived through brutal service experiences. He lived a great life, but, in his time, PTSD was not a medical diagnosis, and talking about these experiences was not something that was natural. But my father did recognize the issues about trauma and would say that some people were ‘just not right’ after the war.”

PTSD has been recognized for more than three decades, but it remains difficult to comprehend, even among health-care professionals, said Tiffany M. Osborn, MD, a professor of surgery and emergency medicine who specializes in critical care.

“People can see a patient in a wheelchair and understand,” Osborn said. “They can see a person walking with a seeing eye dog and know the person is blind. But people cannot see traumatic events that have scarred a person’s heart or changed the way a person thinks. I once heard someone who was the victim of a home invasion say that she knew she was getting better when she could go to bed without wearing her running shoes.

“When we cannot see an illness, it has no context,” Osborn said. “This causes many of us to revert to the context of our own lives, and the actions of someone with PTSD may not make sense. We often think there may be a problem with the person. However, the ‘problem’ stems from our lack of information. We have not taken the time to understand the person or see their actions through the lens of their experiences. That may be the root of many challenges in the world today.”

For more information on next year’s medical book club and related on-campus activities, please contact the Center for History of Medicine.

Robert Boston

Robert Boston