Boosting brain’s waste removal system improves memory in old mice

Research opens door to developing therapies for neurodegenerative diseases

Kyungdeok Kim

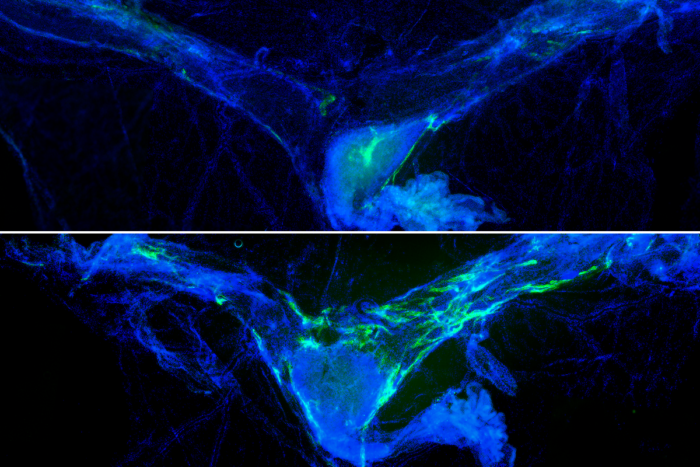

Kyungdeok KimAging compromises the lymphatic vessels (green) in tissue called the meninges (blue) surrounding the brain, disabling waste drainage from the brain and impacting cognitive function. Researchers at WashU Medicine boosted lymphatic vessel integrity (bottom) in old mice and found improvements in their memory compared with old mice without rejuvenated lymphatic vessels (top).

As aging bodies decline, the brain loses the ability to cleanse itself of waste, a scenario that scientists think could be contributing to neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, among others. Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report they have found a way around that problem by targeting the network of vessels that drain waste from the brain. Rejuvenating those vessels, they have shown, improves memory in old mice.

The study, published online March 21 in the journal Cell, lays the groundwork to develop therapies for age-related cognitive decline that overcome the challenges faced by conventional medications that struggle to pass through the blood-brain barrier to reach the brain.

“The physical blood-brain barrier hinders the efficacy of therapies for neurological disorders,” said Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator at WashU Medicine. “By targeting a network of vessels outside of the brain that is critical for brain health, we see cognitive improvements in mice, opening a window to develop more powerful therapies to prevent or delay cognitive decline.”

Waste removal improves memory

Kipnis is an expert in the blossoming field of neuroimmunology, the study of how the immune system affects the brain in health and disease. A decade ago, Kipnis’ lab discovered a network of vessels surrounding the brain — known as the meningeal lymphatics — in mice and humans that drains fluid and waste into the lymph nodes, where many immune system cells reside and monitor for signs of infection, disease or injury. He and colleagues also have shown that some investigational Alzheimer’s therapies are more effective in mice when paired with a treatment that improves drainage of fluid and debris from the brain.

Beginning at about age 50, people start to experience a decline in brain fluid flow as part of normal aging. For the new study, Kipnis collaborated with Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, Professor of Pathology, and asked if enhancing the function of an old drainage system can improve memory.

To test the memory of mice, the researchers placed two identical black rods in the cage for twenty minutes for old mice to explore. The next day, the mice received one of the black rods again and a new object, a silver rectangular prism. Mice that remember playing with the black rod will spend more time with the new object. But old mice spend a similar amount of time playing with both objects.

The first author of the new study, Kyungdeok Kim, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Kipnis lab, boosted functioning of the lymphatic vessels in old mice with a treatment that stimulates vessel growth, enabling more waste to drain out of the brain. He found that the older mice with rejuvenated lymphatic vessels spent more time with the new object – an indicator of improved memory – compared with the older mice not given the treatment.

“A functioning lymphatic system is critical for brain health and memory,” said Kim. “Therapies that support the health of the body’s waste management system may have health benefits for a naturally aging brain.”

Brain’s overwhelmed cleaning crew

When the lymphatic system is so impaired that waste builds up in the brain, the burden of cleaning falls to the brain’s resident immune cells, called microglia. But this local cleaning crew fails to keep up with the mess and gets exhausted, Kipnis explained.

The new study found that the overwhelmed cells produce a distress signal, an immune protein called interleukin 6, or IL-6, that acts on brain cells to promote cognitive decline in mice with damaged lymphatic vessels. Examining the brains of such mice, the researchers found that neurons had an imbalance in the types of signals they receive from surrounding brain cells. In particular, neurons received fewer signals that function like noise-canceling headphones among the cacophony of neuron communications. This imbalance, caused by increased IL-6 levels in the brain, led to changes in how the brain is wired and affected proper brain function.

In addition to improving memory in the aged mice, the lymphatic vessel-boosting treatment also caused levels of IL-6 to drop, restoring the noise-canceling system of the brain. The findings point to the potential of improving the health of the brain’s lymphatic vessels to preserve or restore cognitive abilities.

“As we mark the 10th anniversary of our discovery of the brain’s lymphatic system, these new findings provide insight into the importance of this system for brain health,” said Kipnis. “Targeting the more easily accessible lymphatic vessels that are located outside the brain may prove to be an exciting new frontier in the treatment of brain disorders. We may not be able to revive neurons, but we may be able to ensure their most optimal functioning through modulation of meningeal lymphatic vessels.”