Brain scans of children with Tourette’s offer clues to disorder

Differences noted in brain regions involving sensation, sensory processing

Kevin J. Black

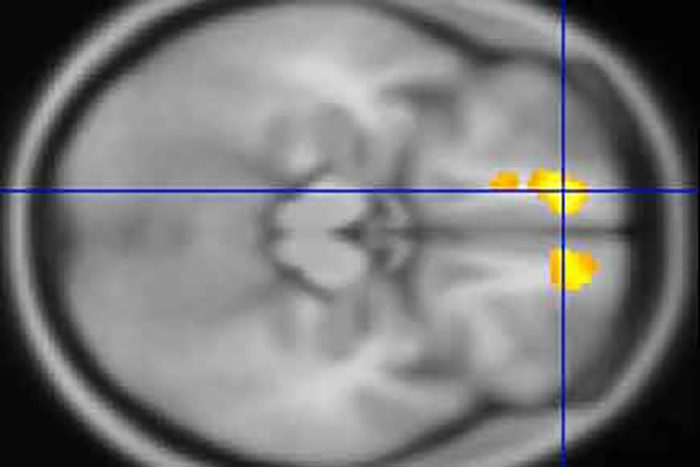

Kevin J. BlackResearchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified areas in the brains of children with Tourette’s syndrome that appear markedly different from the same areas in brains of children who don’t have the disorder. Above, in a scan of a child with Tourette’s, yellow indicates an area with less white matter than in the same brain region in kids who don't have the disorder. The scans also revealed areas in the brains of kids with Tourette's that have more gray matter than in children without the condition.

Using MRIs, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified areas in the brains of children with Tourette’s syndrome that appear markedly different from the same areas in the brains of children who don’t have the neuropsychiatric disorder.

The findings were published online Oct. 25 in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Tourette’s syndrome is defined by tics — involuntary, repetitive movements and vocalizations. Scientists estimate that the condition affects roughly one to 10 kids out of every 1,000 children.

“In this study, we found changes primarily in brain regions connected to sensation and sensory processing,” said co-principal investigator Kevin J. Black, MD, a professor of psychiatry.

Differences in those brain regions make sense, Black said, because many people with Tourette’s explain that their tics occur mainly as a response to unusual sensations. The feeling that a part of the body doesn’t seem right, for example, prompts an involuntary sigh, vocalization, cough or twitch.

“Just as you or I might cough or sneeze due to a cold, a person with Tourette’s frequently will have a feeling that something is wrong, and the tic makes it feel better,” Black said. “A young man who frequently clears his throat may report that doing so is a reaction to a tickle or some other unusual sensation in his throat. Or a young woman will move her shoulder when it feels strange, and the movement, which is a tic, will make the shoulder feel better.”

In the largest study of its kind, the researchers conducted MRI scans at four U.S. sites to study the brains of 103 children with Tourette’s and compared them with scans of another 103 kids of the same age and sex but without the disorder. The scans of the children with Tourette’s revealed significantly more gray matter in the thalamus, the hypothalamus and the midbrain than in those without the disorder.

The gray matter is where the brain processes information. It’s made up mainly of cells such as neurons, glial cells and dendrites, as well as axons that extend from neurons to carry signals.

In kids with Tourette’s, the researchers also found less white matter around the orbital prefrontal cortex, just above the eyes, and in the medial prefrontal cortex, also near the front, than in kids without the condition.

White matter acts like the brain’s wiring. It consists of axons that — unlike the axons in gray matter — are coated with myelin and transmit signals to the gray matter. Less white matter could mean less efficient transmission of sensations, whereas extra gray matter could mean nerve cells are sending extra signals.

Black said it’s not possible to know yet whether the extra gray matter is transmitting information that somehow contributes to tics or whether reduced amounts of white matter elsewhere in the brains of kids with Tourette’s may somehow influence the movements and vocalizations that characterize the disorder. But he said that discovering these changes in the brain could give scientists new targets to better understand and treat Tourette’s.

“This doesn’t tell us what happened to make the brain look this way,” Black explained. “Are there missing cells in certain places, or are the cells just smaller? And are these regions changing as the brain tries to resist tics? Or are the differences we observed contributing to problems with tics? We simply don’t know the answers yet.”

Black said the researchers will aim to replicate these findings in additional patients and determine if and how the brain regions they identified may contribute to Tourette’s syndrome, with a goal of developing more effective therapies.