Breath carries clues to gut microbiome health

Findings in children, mice could pave way to new diagnostic tools, faster treatment

Sara Moser/WashU Medicine

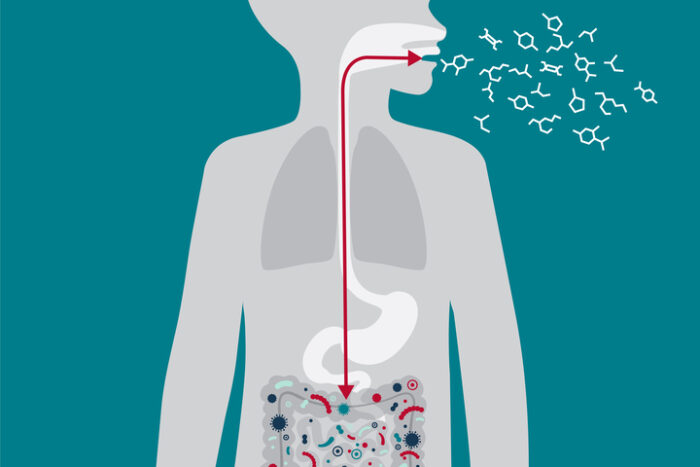

Sara Moser/WashU MedicineWashU Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researchers found that an analysis of compounds exhaled in breath can be used to infer which microbes are living in the gut, paving the way for a rapid, non-invasive breath test to monitor and diagnose gut health issues.

The human gut is home to trillions of beneficial microbes that play a crucial role in health. Disruptions in this delicate community of bacteria and viruses — called the gut microbiome — have been linked to obesity, asthma and cancer, among other illnesses. Yet quick diagnostic tools to identify issues within the microbiome that could be addressed to treat these conditions are lacking.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia have shown that disease-associated bacteria in the gut can be detected through exhaled breath. They found that chemicals released by gut microbes and captured from the breath of children and mice can reveal the composition of the bacteria living in the intestines. They also showed that breath samples from children with asthma could predict the presence of the bacterium linked to the condition.

The findings appear Jan. 22 in Cell Metabolism and could pave the way for a rapid, non-invasive test to monitor and diagnose gut health issues simply by breathing into a device.

“Rapid assessment of the gut microbiome’s health could significantly enhance clinical care, especially for young children,” said Andrew L. Kau, MD, PhD, an associate professor in the John T. Milliken Department of Medicine at WashU Medicine and senior author on the study. “Early detection could lead to prompt interventions for conditions like allergies and serious bacterial infections in preterm infants. This study lays the groundwork for developing such crucial diagnostic tools.”

Sara Moser/WashU Medicine

Sara Moser/WashU MedicineIn the process of digesting food that the body cannot, microbes release compounds, known as volatile organic compounds, that are excreted from the body through exhaled breath. The researchers, including Kau; first author Ariel J. Hernandez-Leyva, a WashU Medicine MD/PhD student; and co-corresponding author Audrey R. Odom John, MD, PhD, the Stanley Plotkin Endowed Chair in Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, wondered if the types of compounds in breath can help identify the bacterial composition of the gut microbiome.

Hernandez-Leyva and his colleagues conducted a clinical study at WashU Medicine of children ages six to 12. They analyzed the breath and stool of 27 healthy children for microbe-derived compounds and gut microbes, respectively, to figure out which microbes were linked with which breath compounds.

The team found that the compounds in the children’s breath matched the compounds known to be produced by the very microbes present in their stool, confirming that breath is a good proxy for the microbial community in the gut. They obtained similar results in mice by transplanting bacteria into animals without gut microbes of their own and finding again that gut bacteria can be identified from breath compounds.

The researchers also compared breath and stool samples from healthy children to samples from children with asthma. Pediatric asthma — which affects nearly 5 million kids in the U.S. — is associated with an increased intestinal abundance of the bacterium Eubacterium siraeum. Through breath analysis, they were able to predict the abundance of E. siraeum in kids with asthma.

Such information on E. siraeum abundance would be valuable for spotting early signs of microbiome changes that might exacerbate asthma symptoms. Similarly, routine screening of microbiome health through breath tests in infants born prematurely, for instance, might spot disruptions to the developing microbiome that portend infection.

The results of the new study may help inform the development of a non-invasive microbiome breath test. Breath tests for detecting microbes have previously been developed by WashU Medicine researchers, including one that can detect the COVID-19 virus in less than a minute.

“One of the key barriers to integrating our knowledge of the microbiome into clinical care is the time it takes to analyze the data on the microbiome,” said Hernandez-Leyva. “Breath analysis offers a promising, non-invasive way to probe the gut microbiome and can transform how we diagnose disease in medicine.”