Cause of rare, fatal disorder in young children pinpointed

Proof-of-concept drug therapy benefits mouse model of Krabbe disease

Sands Lab

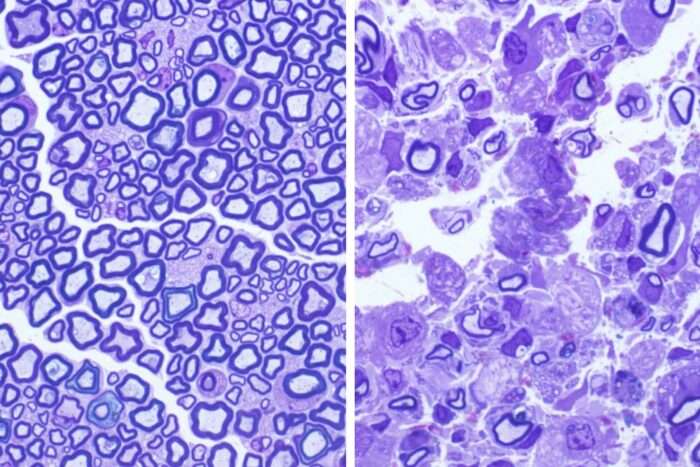

Sands LabScientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have pinpointed the precise cause of Krabbe disease, a neurodegenerative condition that usually causes death by age 3. Pictured on the left is a normal cross section of a mouse nerve. A protective layer of myelin surrounds the nerve wires, called axons. On the right is a cross section of a nerve from a mouse with Krabbe disease, which causes the loss of this protective layer of myelin and subsequent nerve destruction.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis appear to have solved a decades-long mystery regarding the precise biochemical pathway leading to a fatal genetic disorder in children that results in seizures, developmental regression and death, usually around age 3. Studying a mouse model with the same human illness — called Krabbe disease — the researchers also identified a possible therapeutic strategy.

The research is published Sept. 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Patients with infantile globoid cell leukodystrophy, also known as Krabbe disease, gradually lose the protective covering that insulates axons, the wiring of the nervous system. The rare condition — affecting about 1 in 100,000 births — is typically diagnosed before age 1 and progresses rapidly.

Scientists long have suspected that nerve insulation is destroyed in this disorder because of a buildup of a toxic compound called psychosine. Patients with the inherited disorder are missing an important protein involved in breaking down psychosine. But the source of psychosine in Krabbe disease has been elusive, making the problem impossible to correct.

“Krabbe disease in infancy is invariably fatal,” said senior author Mark S. Sands, PhD, a professor of medicine. “It’s a heartbreaking neurodegenerative disease first described more than a century ago, but we still have no effective treatments. For almost 50 years, we have assumed the psychosine hypothesis was correct — that a toxic buildup of psychosine is the cause of all the problems. But we’ve never been able to prove it.”

Surprisingly, Sands and his team, led by graduate student Yedda Li, proved the psychosine hypothesis correct by, essentially, giving the mice another lethal genetic disease.

The scientists showed that mice harboring genetic mutations resulting in Krabbe disease and Farber disease, a lethal condition that results from the loss of a different protein, have no signs of Krabbe disease. The missing protein in Farber disease is called acid ceramidase, and when it is gone, psychosine does not build up, effectively curing Krabbe disease in mice that otherwise would have it.

“We did not expect these mice to survive through embryonic development with the genetic alterations that cause both Farber disease and Krabbe disease,” Sands said. “We felt it was likely that the combination of these genetic problems would be lethal to the mouse embryo, or at least cause some combination of the problems characteristic of both diseases. Not only were the mice alive, we found that they did not have Krabbe disease — despite having the causal genetics — and we tested them for it in every way imaginable. It was shocking.”

Without the toxic buildup of psychosine, Krabbe disease did not develop in these mice, proving the 50-year-old hypothesis.

After identifying acid ceramidase as the trigger of the toxic buildup of psychosine, Sands and his colleagues gave mice with Krabbe disease a drug known to be an acid ceramidase inhibitor. The drug, carmofur, is a common chemotherapy used to treat cancer. The drug modestly extended the lives of mice with a model of Krabbe disease.

“Carmofur is quite toxic by itself, so it would never be used as a treatment for this disease, but we did show a modest therapeutic benefit,” Sands said. “The research demonstrates a proof-of-concept that we can inhibit acid ceramidase with a drug and it will relieve some of the symptoms of Krabbe disease. We will need to strike a balance, though, because inhibiting it too much will cause Farber disease.”

Sands said he hopes researchers specializing in drug development will begin working toward a safe and effective acid ceramidase inhibitor for this disorder.