Female hormones increase risk of vision loss in rare genetic disease

Estrogen triggers immune cells to damage nerves

Joseph A. Toonen

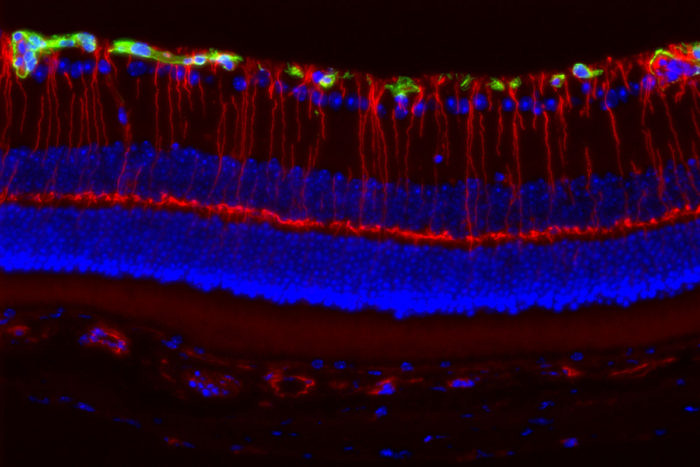

Joseph A. ToonenGirls with a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the Nf1 gene are much more likely to lose their vision than boys with mutations in the same gene. Neurons in the retina of the eye, illuminated by fluorescent markers (above), are more likely to be damaged in female than male mice with Nf1 mutations. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis believe female sex hormones activate immune cells that damage the nerves necessary for vision.

Girls with a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in a gene known as Nf1 are much more likely to lose their vision than boys with mutations in the same gene. And now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis believe they know why: Female sex hormones activate immune cells that damage the nerves necessary for vision.

The study was carried out in mice to mimic a common brain tumor arising in a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). The findings, available online in The Journal of Experimental Medicine, suggest that blocking female sex hormones or suppressing the activation of specific immune cells in the brain could save the eyesight of children with NF1-associated brain tumors.

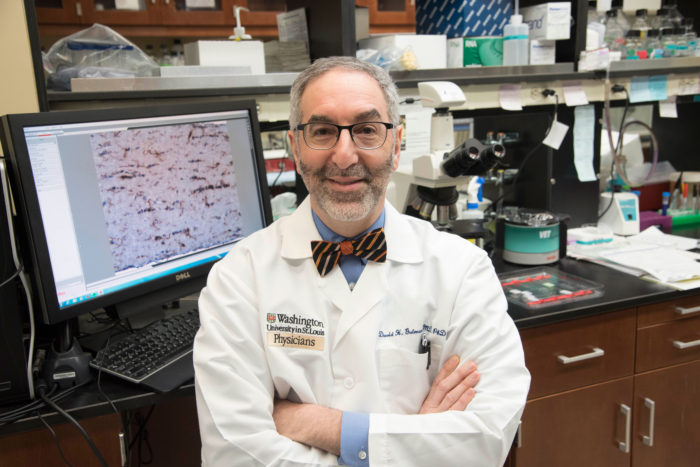

“The take-home message is that a child’s sex matters when it comes to this disease,” said David H. Gutmann, MD, PhD, the David O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology and the study’s senior author. “We’ve identified what leads to this difference in vision loss, and that suggests novel potential therapies to treat this serious medical problem in children. Understanding why boys and girls with mutations in the same gene have different outcomes presents unprecedented opportunities to fix the problem.”

NF1 causes children and adults to develop brain and nerve tumors. These tumors are typically benign – meaning they don’t spread to other parts of the body and lead to death – but they still can have serious consequences.

Nearly 20 percent of children with NF1 develop brain tumors that involve the optic pathway, affecting the nerves that carry vision-related signals from the eye to the brain. In some children, these tumors cause vision loss; however, it is not currently possible to predict who will experience vision decline and who will not.

Two years ago, Gutmann and colleagues were the first to report that girls with NF1 were five times more likely to lose their sight than boys, even though there were no clear differences in the size of the tumors between boys and girls.

To discover why girls are more likely to experience vision decline from their tumors, Gutmann, postdoctoral researcher Joseph A. Toonen, PhD, and colleagues studied mice with Nf1 gene mutations specifically engineered to develop tumors on the optic pathway. Both male and female mice developed tumors that were identical in size and growth rates; however, only the female mice exhibited significant nerve damage and vision loss.

Robert Boston

Robert BostonThe researchers found that the tumors contain a type of immune cell called microglia. Strikingly, female mice had three times more microglia within these tumors than male mice. When activated, microglia release a range of toxic compounds that can cause collateral damage to nearby nerve cells. When they are activated, they release those compounds and sometimes cause collateral damage to nearby cells. The researchers found that the microglia within the optic tumors from female mice were activated, and the neurons near the tumors were damaged.

To test whether sex hormones could account for these differences, the researchers removed the ovaries from female mice and the testes from male mice. The number of damaged and dying cells in the retina – a light-sensitive layer of nervous tissue in the eye – did not change in the castrated males. But in the females without ovaries, fewer cells in the retina died and the number of activated microglia within the tumors was also decreased. These findings suggest that female sex hormones may cause microglial activation and subsequent neuronal damage.

When researchers used a drug to block the action of the female sex hormone in female mice carrying the Nf1 mutation, they saw a drop in the number of activated microglia and a decrease in retinal damage and nerve cell death. Moreover, the researchers identified the specific nerve-damaging toxins produced by these activated microglia. Future therapies to attenuate vision loss in children with NF1-optic tumors might target these compounds.

Gutmann stressed that boys with NF1 also experience vision loss, just not as frequently as girls, and that male NF1 mice harbor some activated microglia within their tumors. He believes that the process of microglial activation and ensuing neuronal damage is the same in males and females, but that the presence of female sex hormones increases the microglial activation, leading to greater optic nerve damage and vision loss.

“This sex difference has turned out to be critical for us to begin to unravel the causes of the vision loss in NF1-optic tumors,” Gutmann said. “We would not have identified the key molecular signals that promote neuronal death without these sex differences. Moreover, these findings have implications beyond brain tumors and have led us to explore sex differences in other NF1 neurological problems, including autism, sleep and attention deficit.”

Since his team discovered the influence of sex on vision loss, Gutmann has begun to make changes to his clinical practice.

“We have been looking for ways to identify children at highest risk for vision loss, and now we think that one important factor is being a girl,” Gutmann said. “I haven’t relaxed my concern for the boys, but it’s certainly heightened my concern for the girls.”