Hard-to-treat depression in seniors focus of $13.5 million study

Goal is to identify strategies most likely to work for specific patients

Robert Boston

Robert BostonMore than half of seniors with clinical depression remain depressed even after treatment with antidepressant drugs. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis plan to evaluate strategies involving augmenting treatment with a second antidepressant drug or switching to a different drug altogether in an attempt to learn what works best for individual patients.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are launching a study aimed at identifying effective treatment methods for seniors with depression that does not respond to standard medications.

Nearly one-third of the 14 million Americans who live with clinical depression don’t get satisfactory relief from therapies prescribed to treat the disorder. And among older adults, more than half remain depressed even after treatment with antidepressant drugs.

With a $13.5 million grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute — an independent, nonprofit organization authorized by Congress under the Affordable Care Act — the researchers will study 1,500 adults over age 60 who have depression but have not responded to treatment.

“Older adults who are prescribed antidepressants often find that they don’t get better with the first or second medication they are prescribed,” said principal investigator Eric J. Lenze, MD, a professor of psychiatry. “So what should they get? This will be the largest and, we hope, the definitive study to answer that question. This study will show us which treatments work best and which are safest, and it will help us personalize treatment.”

The study will answer those questions by employing two treatment approaches: augmentation and switching of antidepressants. Every patient in the study will get treatment for 10 weeks, during which they either will receive an additional drug (augmentation) or a substitute medication in place of the antidepressant they already take (switch).

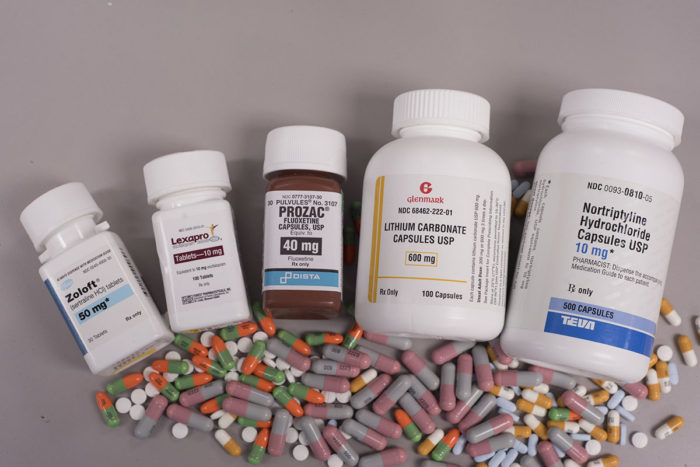

“Most patients will come to us already taking antidepressants called SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), which include Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft or Lexapro,” Lenze said. “For patients in the augmentation branch of the study, we’ll add a second antidepressant to the one they’re already taking. Doctors often use this augmentation strategy in other medical illnesses such as high blood pressure or diabetes, in which a patient taking a single medication is not getting enough benefit. At that point, they add a second medication.”

In this study, the researchers will augment the patients’ SSRI drugs with aripiprazole (Abilify) or bupropion (Wellbutrin). A second group of patients will discontinue their current antidepressant drugs and switch to taking only bupropion.

“In clinical practice, we usually augment treatment with an additional drug, but we really don’t know whether that’s a better option for these patients,” Lenze said. “Older adults, in particular, tend to be on more medications already, so adding another drug can be risky simply because that person is taking more medications. Switching to a different drug may work better, but right now, we don’t know what’s best.”

Lenze said patients in the study will be monitored closely for 10 weeks. If after 10 weeks they no longer are considered clinically depressed, they will be finished with the study. However, the researchers will follow them for a year to see whether their depression remains at bay.

Subjects who remain depressed after 10 weeks of receiving an additional antidepressant or after having been switched to a new drug will go into a second phase of the study. That phase again will involve augmenting or switching medications, but in the second phase, Lenze and his colleagues will use different, longer-standing medications.

“If a person doesn’t benefit from adding a second antidepressant, perhaps they’ll get relief if their doctor adds lithium,” Lenze suggested. “Decades ago that’s what psychiatrists used to do. But that isn’t done much anymore because lithium can be a difficult drug to use.”

He explained that patients taking lithium need close monitoring of levels of the drug in the bloodstream and kidney function.

“Lithium is more difficult to use, but there’s a real question about whether we’ve let a good treatment option fall by the wayside,” Lenze said. “With the proper precautions, lithium may be a highly effective option that could help more patients.”

Others who remain depressed after the first 10 weeks of the study will be switched to a different, older drug that has not been used as widely in recent years: nortriptyline.

“It’s a tricyclic antidepressant, a class of drugs developed before the SSRIs came along,” Lenze said. “We tend not to use these drugs as much because they require additional patient monitoring for blood levels of the drug. But again, we want to learn whether this older option might be an effective and practical option for some patients whose depression doesn’t respond to the drugs we use more frequently.”

In addition to following people from the St. Louis area, the study also will involve centers in Los Angeles, western Pennsylvania, New York City and Toronto. Everyone who volunteers for the study will receive some form of treatment; no one will be randomly selected to receive an inactive placebo. The researchers may recommend adjustments to medications based on symptoms or side effects, but subjects will receive treatment from their regular doctors. As the study progresses, investigators will check in with patients every two weeks to ask about symptoms and side effects.

“We may tell the prescribing doctor that a person is tolerating the medicine well but still is depressed, so we might recommend they increase the dose,” Lenze said. “Or we might find a person isn’t tolerating the medication, so we’d recommend reducing the dose or stopping the treatment altogether.

“We hope this study will lead to fine-grained observations about not just whether these treatment strategies work, but whether they work for particular kinds of patients,” he said. “There’s a real chance when the study is complete that we’ll have a better idea of how to tailor medications to older adults with depression.”

For more information, call 314-747-5706, or e-mail HealthyMind@psychiatry.wustl.edu.