Higher blood levels of omega-3 may help depression in heart patients

Patients with higher blood levels at start of study responded better to omega-3 supplements

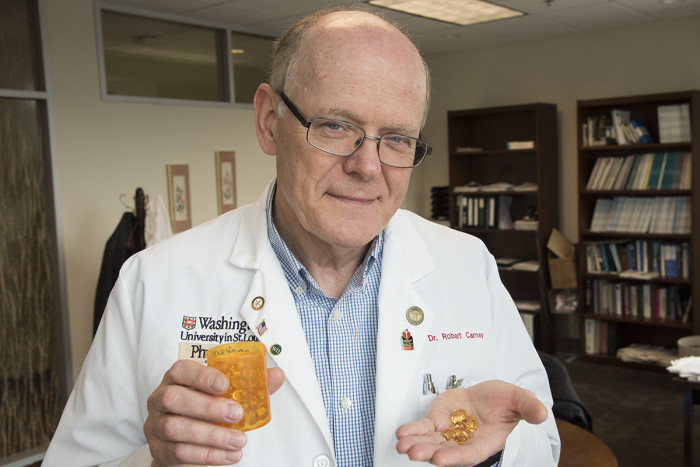

Robert Boston

Robert BostonNew research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that initial levels of omega-3 fatty acids in a heart patient’s blood have a significant impact on whether that person will respond to omega-3 supplements to treat depression.

Despite earlier reports to the contrary, patients suffering from heart disease and depression may benefit from taking supplements of omega-3 fatty acids.

New research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that initial levels of omega-3 fatty acids in a heart patient’s blood have a significant impact on whether that person will respond to omega-3 supplements to treat depression.

“We found that people with higher levels of omega-3 in their blood may benefit more from additional omega-3, in the form of supplements, than those whose blood levels of the fatty acids were lower at the outset,” said principal investigator Robert M. Carney, PhD, professor of psychiatry. “Because depression is linked to heart attacks and sudden cardiac death in patients with cardiovascular disease, we have been trying to figure out how best to improve depression in these patients. These findings offer potential answers for a very significant problem.”

The findings are published in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

To determine whether omega-3 supplements might be of benefit to such people, in a 2009 study of 122 patients, Carney’s group treated some of those patients with omega-3 supplements and an antidepressant drug, while the others received the antidepressant alone. But they found no additional benefit for depression symptoms in the group that received omega-3 compared with those who received the drug alone.

Carney and his team took another look at the earlier data and noticed that people who began the initial study with higher levels of omega-3 in their blood had significant improvements in their symptoms of depression.

“Typically in drug trials, you expect every subject to start out at a blood level of zero of the drug you’re studying,” he said. “Then the subjects receive a placebo or the active drug. But in studies looking at a naturally occurring substance like omega-3, people tend to come in with different amounts in their blood, depending on their diet, how well they metabolize omega-3, and other factors.”

The researchers found that although some people with high blood levels of omega-3s eat a lot of fatty fish, others simply maintain higher levels for reasons that are not well-understood.

Robert Boston

Robert BostonSome people may clear omega-3s from their systems more rapidly or don’t absorb them as well. But Carney believes one reason behind conflicting findings about the effectiveness of omega-3s for heart disease and depression may be due to researchers not noting omega-3 levels at the beginning of studies.

“Most researchers have relied on dietary information,” he said. “You can make a crude estimate based on that information, but we found in our new study that there was a relatively weak correlation between what patients report about omega-3 in their diets and their actual blood levels.”

Armed with new information about the importance of omega-3 levels in the blood, Carney’s team has launched a new clinical trial. They’re measuring blood levels of omega-3 and then giving subjects slightly higher levels of specific types of omega-3 fatty acids to see whether the treatments affect depression. They currently are recruiting volunteers for the study. For more information, contact Carol Sparks at 314-286-1315 or by e-mail at sparks@bmc.wustl.edu.