Immunotherapy reduces plaque in arteries of mice

Harnessing T cells could expand heart disease therapies beyond lowering cholesterol

Junedh Amrute

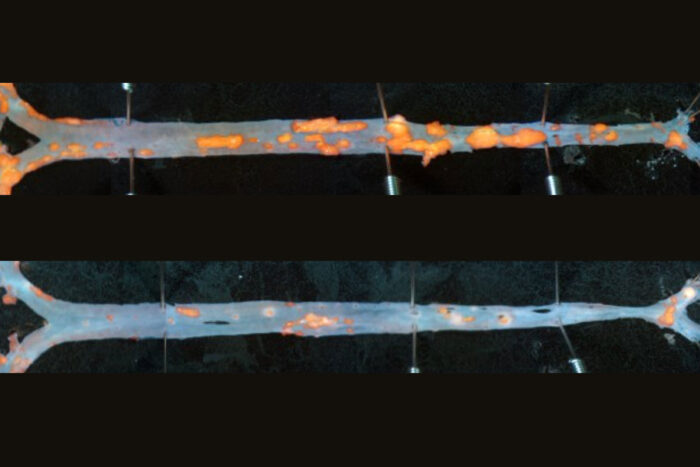

Junedh AmruteAn immunotherapy reduces plaque in the arteries of mice, offering a potential new strategy to treat cardiovascular disease, according to a study led by WashU Medicine researchers. An artery from an untreated mouse (top) shows more plaque (orange) than that of a mouse treated with the antibody-based immunotherapy (bottom).

Scientists have designed an immunotherapy that reduces plaque in the arteries of mice, presenting a possible new treatment strategy against heart disease. The antibody-based therapy could complement traditional methods of managing coronary artery disease that focus on lowering cholesterol through diet or medications such as statins, according to the findings of a new study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Such an immunotherapy could especially help patients who already have plaque in their coronary arteries and remain at high risk of heart attack even if they’re able to achieve low cholesterol levels in the blood.

The study is published Jan. 29 in the journal Science.

The novel therapy uses a synthetic antibody — a type of lab-generated protein — to destroy a harmful type of cell located within blood vessel walls that plays a central role in driving inflammation and dangerous plaque formation in the arteries of the human heart. These cells directly contribute to coronary artery disease, in which atherosclerotic plaque builds up in the arteries that feed blood to the heart.

Eliminating these cells in mouse models of atherosclerosis reduced the amount of plaque, diminished plaque inflammation, and improved the stability of the plaque, which is important for preventing heart attacks.

“This type of antibody therapy was originally designed to target cancers, such as lymphoma, and we imagine a similar precision medicine approach for cardiovascular disease,” said senior author Kory J. Lavine, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine in WashU Medicine’s Cardiovascular Division. “Cholesterol-lowering medications are mainly preventive, which does not substantially reduce plaques that are already there. An immunotherapy that can reduce inflammation and dangerous plaque in patients with more advanced atherosclerosis is an exciting prospect.”

Targeting the culprit

Atherosclerosis is an extremely common inflammatory process that chronically damages artery walls, often caused by a combination of factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and high blood sugar. Harmful immune cells accumulate and plaque builds up, forming a lesion that resembles a scar. As part of the process, structural cells in the arteries called vascular smooth muscle cells become dysfunctional, migrating to parts of the artery where they shouldn’t be. In these new locations, they become what are called modulated smooth muscle cells, which release signals that attract and activate inflammatory immune cells that drive ongoing plaque formation and instability.

Lavine’s team worked with researchers at the biotech company Amgen on studies of an antibody-based molecule that could grab on to modulated smooth muscle cells and enlist the destructive power of the immune system to eliminate them and their damaging downstream effects. Called a bispecific T cell engager (or BiTE) molecule, this engineered molecule draws a type of immune cell called a T cell to a target cell that should be eliminated from the body, whether it’s a cancer cell or, in this case, a modulated smooth muscle cell. But first, the researchers needed to identify a specific feature of the cells that the BiTE molecule could home in on.

To find a molecular signature of modulated smooth muscle cells, Lavine’s team performed a cutting-edge analysis of 27 human coronary arteries from patients undergoing heart transplantation. They used a technique called single-cell profiling that revealed the active genes and proteins in each of the 150,000-plus cells from these samples. They combined this information with spatial data specifying the locations of the various cells and cell types in the 3D structure of the artery, including within the arterial plaque.

Using this single-cell and spatial “atlas” of human coronary artery disease, the investigators pegged a molecule called fibroblast activation protein located on the surface of modulated smooth muscle cells that could be used as a homing target by BiTE molecules. Eliminating these harmful cells with the BiTE molecules significantly reduced atherosclerosis in mice modeling the disease compared with untreated mice.

“We found that these cells are located in areas of the plaque that are particularly vulnerable to rupture, which is the primary cause of heart attacks,” said Lavine, who is also the director of the WashU Medicine Center for Cardiovascular Research. “What this BiTE molecule seems to be doing in removing these damaging cells is leading to an improved wound healing process, reducing inflammation and the amount of plaque, and increasing the stability of any plaque that remains.”

The researchers also employed an imaging tracer molecule that targets fibroblast activation protein, allowing them to use a PET/CT scan to locate modulated smooth muscle cells. In collaboration with their international team of scientists, they tested this tracer in patients with coronary artery disease and found that it lit up coronary plaques in the scans.

Lavine said they are planning more imaging studies and further optimizing the BiTE molecule to explore its potential as a safe and effective treatment for atherosclerosis. They also are aiming to see if their imaging tracer could be used to distinguish stable versus unstable plaques, so they can try to prevent heart attacks in patients at the highest risk.