Improved orthopedic health doesn’t necessarily mean improved mental health

Study indicates anxiety improves only with major health progress, but depression does not

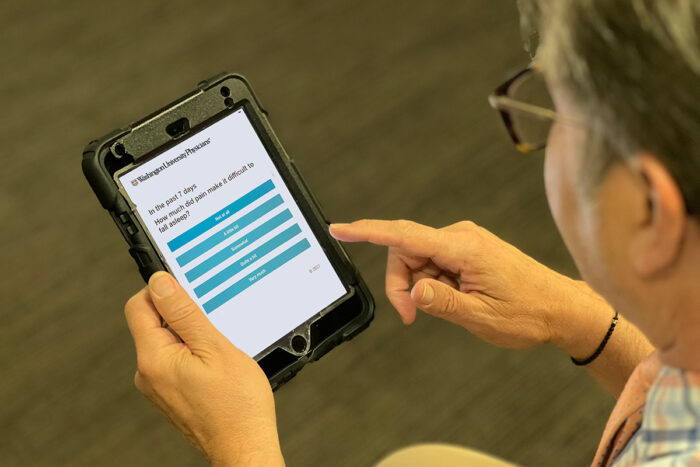

Matt Miller/Amanda Lovelace

Matt Miller/Amanda LovelaceOrthopedic clinics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis ask patients to fill out an electronic questionnaire at each visit. Analyzing data from questions about anxiety and depression, researchers have found that as patients' musculoskeletal health improves, anxiety and depression don't necessarily follow suit.

Pain from an injured back, shoulder or hip can make a person feel frustrated, anxious or even depressed. Many in health care may assume that when such injuries heal, mental health also improves. But a new study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that over the long term, symptoms of depression and anxiety often don’t subside when an orthopedic patient’s physical pain improves.

The researchers studied de-identified data from the medical charts of more than 11,000 patients treated in Washington University orthopedic clinics over a period of almost seven years. They found that symptoms of anxiety improved only when a patient had major improvements in physical function — but that even significant improvements in physical function were not associated with meaningful improvements in depression.

The study is published June 28 in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“We wanted to find out if patients have fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression as physical function improves and pain lessens,” said senior author Abby L. Cheng, MD, an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery. “The answer is that they mostly do not.”

Each orthopedic patient treated at Washington University clinics is given a tablet upon check-in with a number of questions about whether their orthopedic problems are interfering with their lives. The list includes questions such as: “In the past seven days, how much did pain interfere with your ability to do household chores?” and, “In the past seven days, how much did pain make it difficult to fall asleep?” The questionnaire also asks about each person’s mental health and wellness.

“Our goal is to treat a person, not just fix a hip or a knee, and physical problems are connected to mood and anxiety, even to depression,” Cheng said. “Patients have a lot going on, and it’s difficult to provide good care without taking the big picture into account.”

Analyzing answers to the questionnaires, Cheng’s team found that over the course of almost seven years, the mental health of people with orthopedic problems didn’t necessarily improve when their physical symptoms got better.

“Some studies have found that when you treat patients for a specific musculoskeletal problem — perhaps surveying them before and after hip-replacement surgery — some mental health symptoms also will improve, at least in the short term,” Cheng explained. “But looking over the course of several years, we didn’t see those improvements. Patients may be less anxious six months after surgery, but five years down the line the story may be very different. Those symptoms of anxiety often return, although perhaps the focus of the anxiety no longer is related to the patient’s hip or other orthopedic problem.”

Cheng said she was somewhat surprised by the findings, because the general thinking in orthopedics has long been that when physical health improves, mental health will improve, too. But she said that in her practice, she frequently sees people whose physical health has improved — but without dramatic improvements in mental health.

“What was interesting to me was that patients’ anxiety lessened somewhat in cases where patients experienced notable improvements in physical health, but depression did not improve in many such instances,” she said. “As physicians, what we really care about is how patients feel. One patient might be happy because now he or she can walk a mile, and that’s good. But other patients who can walk a mile might not be happy because they no longer can run marathons, and that’s not good. Patient perceptions of their well-being are what are really important, and those don’t necessarily improve when pain diminishes and physical function improves.”