Lithium boosts muscle strength in mice with rare muscular dystrophy

New drug target identified

Andrew Findlay

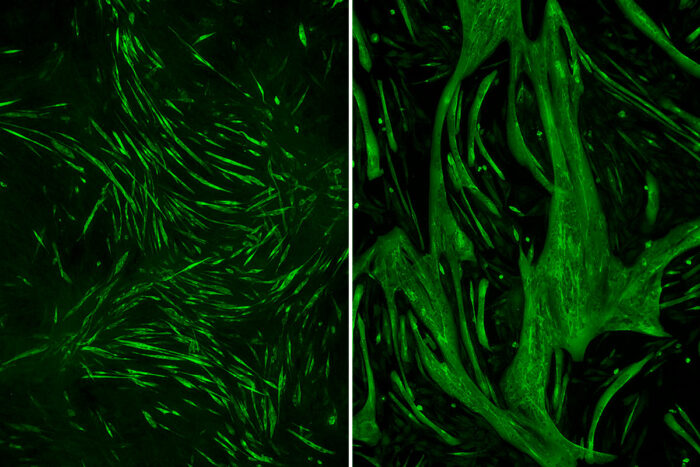

Andrew FindlayRemoving one gene caused normal muscle muscle fibers (left) to grow to three times their normal size (right). Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that targeting a protein related to that gene with lithium can reduce muscle wasting in a rare form of muscular dystrophy.

Standing up from a chair, climbing stairs, brushing one’s hair – all can be a struggle for people with a rare form of muscular dystrophy that causes progressive weakness in the shoulders and hips. Over time, many such people lose the ability to walk or to lift their arms above their heads.

This form of the disease – called limb girdle muscular dystrophy – affects a few thousand people nationwide. Like other rare illnesses, it tends not to attract much attention from researchers and funding agencies, so progress toward developing therapies has been slow. But a team at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis that identified a subtype of the disease in 2012 has shown that lithium improves muscle size and strength in mice with this form of muscular dystrophy. The findings, published April 18 in Neurology Genetics, could lead to a drug for the disabling condition.

“There are no medications available for people with limb girdle muscular dystrophy, so we are very excited to have a good therapeutic target and a potential therapy,” said senior author C. Chris Weihl, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology who treats people with muscular dystrophy at the university’s Neuromuscular Disease Center. “This has been an amazing project. It all began when we diagnosed a patient with muscular dystrophy of unknown cause. Genetic sequencing then helped us identify a new subtype, and we’ve been able to take that all the way through to a possible therapy.”

Limb girdle muscular dystrophy can be caused by variations in any one of more than a dozen different genes. Several years ago, Weihl and colleagues – including neurologists Robert Baloh, MD, PhD, and Matthew Harms, MD – identified two families in which several members had symptoms of the condition but none of the known genetic variants. By analyzing the DNA of affected and unaffected members of both families, the researchers found that a variation in the gene DNAJB6was responsible for their muscle weakness.

While the researchers had found the faulty gene, it wasn’t immediately clear why an alteration to that gene caused people’s muscles to atrophy. To find out, Weihl and co-first authors Andrew Findlay, MD, a clinical fellow in neurology, and Rocio Bengoechea Ibaceta, PhD, a staff scientist, cut the gene out entirely, expecting to see even more muscle loss when the gene was absent.

They found the opposite: Without DNAJB6, muscle fibers grew to three times their normal size.

“When Drew showed me these enormous muscle fibers, I just didn’t understand it,” Weihl said. “But Drew pointed out that we were on the right pathway, but perhaps going the wrong direction. Something in this pathway is important for muscle growth.”

The researchers tried again, this time using genetically modified mice that Weihl and colleagues had engineered in 2015. These mice carried the same genetic variant as the patients, and like the patients, they developed progressive muscle weakness in adulthood. Using muscle from these mice, the researchers discovered that disease variants overactivate a protein that suppresses muscle growth. Moreover, inhibiting the protein – called GSK3beta – with lithium chloride improves mice’s strength and muscle mass.

“Before treatment, mutant mice had roughly one-fifth the strength of the normal mice,” Findlay said. “After a month of treatment, they improved to 75 percent of the normal mice. It’s a big jump.”

Lithium chloride was once sold as table salt but was taken off the shelves in 1949, when doctors realized that sprinkling it liberally on food can be deadly. But other forms of lithium such as lithium carbonate and lithium citrate are used to treat some psychiatric illnesses, so it’s possible a safe form of lithium can be found to treat the rare muscular dystrophy.

“I don’t want people to go out and take lithium chloride right now,” Findlay said. “We’ve shown that this protein is a promising therapeutic target, but more work needs to be done.”

Before any compound targeting the protein is tested in humans, a better understanding of limb girdle muscular dystrophy is needed. The disease is so rare that doctors have not defined how quickly different people lose strength and how the course of the disease differs in people whose condition is caused by variations in different genes.

“We’re at a point where therapeutic development has outpaced our understanding of the natural history of this disease,” Weihl said. “We have a therapeutic target, but we don’t fully understand how patients progress when they’re not treated. We need to understand as many people with this rare disease as possible so when we do start testing an investigational drug, we can be confident that it is changing the course of the disease.”

Weihl, Findlay, and colleagues around the U.S. and U.K. are planning a study of people with limb girdle muscular dystrophy caused by variations in any gene. The study will map disease progression in such people in preparation for upcoming treatment trials. Participants will make annual visits to the neuromuscular clinic to undergo functional assessments such as timed stair climbs and fill out questionnaires rating their ability to perform tasks of daily life.