Med Campus exhibit depicts historical experiences of Black employees, students, patients

WashU Medicine, BJC HealthCare timeline focuses on shared racial history, desegregation

Matt Miller

Matt MillerAmelia Bray-Aschenbrenner, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, reads stories on the newly installed Desegregration History Wall on the Medical Campus.

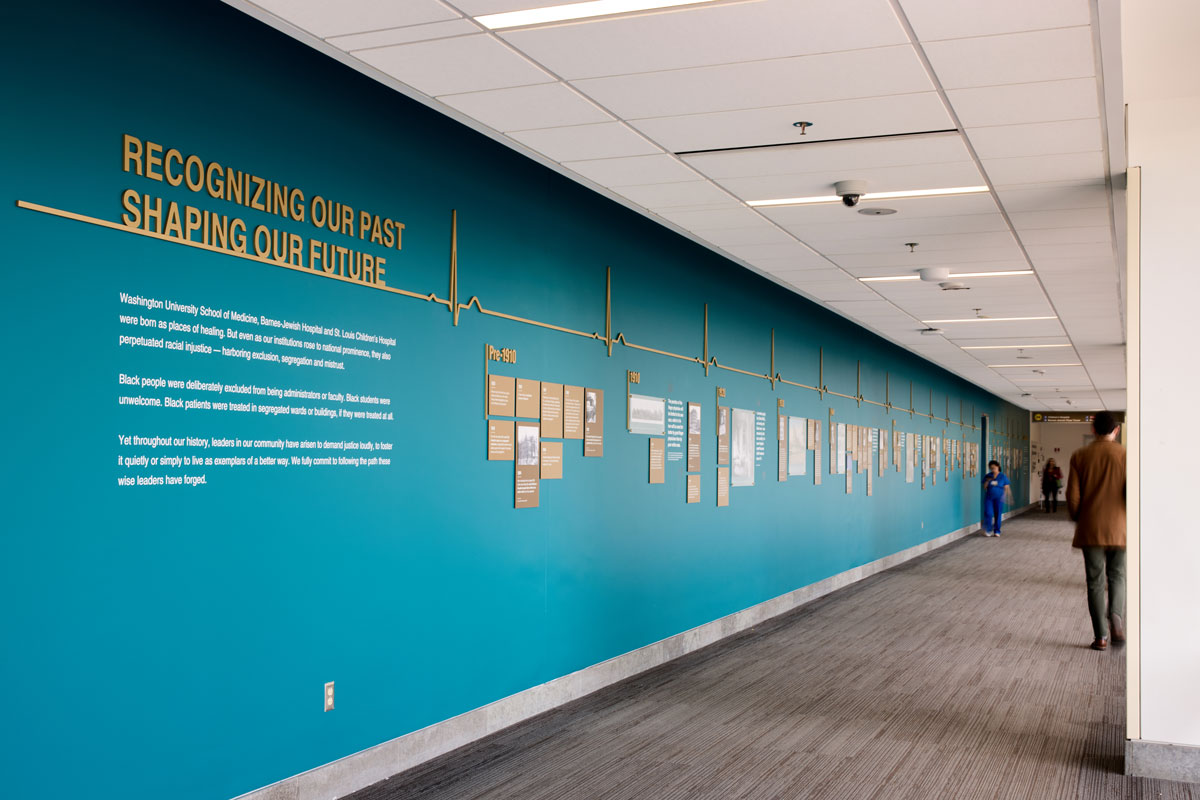

The new exhibit, stretching nearly 50 yards along a prominent wall on the Medical Campus, demands attention. Historical photographs depict the experiences of Black individuals – health-care workers and other employees, patients and students – at Washington University School of Medicine and its partner hospitals.

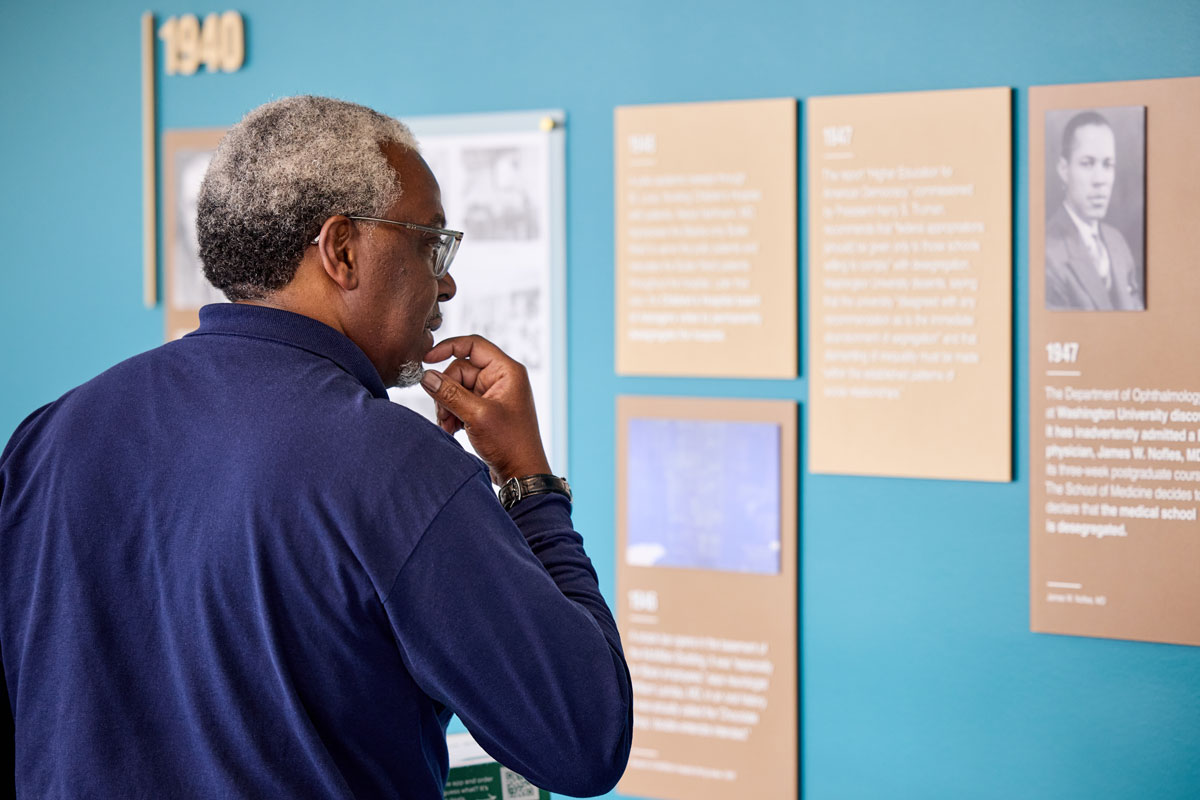

Some images spark discomfort and dismay, recalling a time when most U.S. hospitals and academic institutions were racially segregated. But other images inspire, highlighting the barrier-breaking achievements of Black people as well as activism by students, faculty and other employees to end segregation.

One photo, for example, shows young Black patients in a sparse, segregated ward at St. Louis Children’s Hospital in 1923. Later, in 1946, when a polio epidemic swept through St. Louis, the ward’s Black patients were integrated into other areas of the hospital so children with polio – regardless of race – could be isolated in the ward away from other patients. These actions spurred the Children’s board to vote that same year to permanently desegregate the hospital.

Altogether, this new permanent exhibit — the Desegregation History Wall – includes 46 images and accompanying narratives. It was installed by WashU Medicine, in collaboration with BJC HealthCare, in a heavily trafficked walkway on the second floor of the BJC Institute of Health. The exhibit also can be viewed online.

The timeline, which spans two centuries, examines the past through an unfiltered lens while also showing how the Medical Campus has progressed in its commitment to racial equity and inclusion in patient care, research and education.

“Acknowledging these injustices and celebrating the courageous men and women who worked — and those who continue to work — to bring about needed change are steps toward healing and building trust, and a reminder for us as we continue our very important efforts to ensure equitable access to health care and opportunity on our Medical Campus and in the wider community,” said David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, the George and Carol Bauer Dean of the School of Medicine, and the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor.

Matt Miller

Matt MillerThese courageous people include Helen E. Nash, MD, who in 1949 became the first Black woman to join the WashU Medicine faculty. She went on to treat patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital for more than 40 years. Nash also was a beloved mentor to many medical students and established scholarships to support their training.

In 2022, Children’s Place between Euclid and Taylor avenues in the heart of the Medical Campus was renamed Nash Way in honor of Nash and her brother Homer E. Nash Jr., MD, who also was on the medical staff at Children’s. Together, they spent decades caring and advocating for generations of children, many of whom were poor and Black, and influenced physicians, trainees and other health-care workers to emphasize health equity in patient care.

Also in 1949, Ernest St. John Simms, a Black researcher, joined the medical school’s research staff and later contributed to the Nobel Prize-winning research of WashU Medicine’s Arthur Kornberg. And in 1962, James L. Sweatt III, MD, became the first Black student to graduate from the School of Medicine. He went on to become a thoracic surgeon in Texas, where he continued to break racial barriers. Sweatt later recalled that he thought “it was routine for all the professors in (WashU Medicine’s) departments to sit around and quiz applicants for admission.” It was not until decades later that he found out that everyone else had been seen by one person “and that was that.”

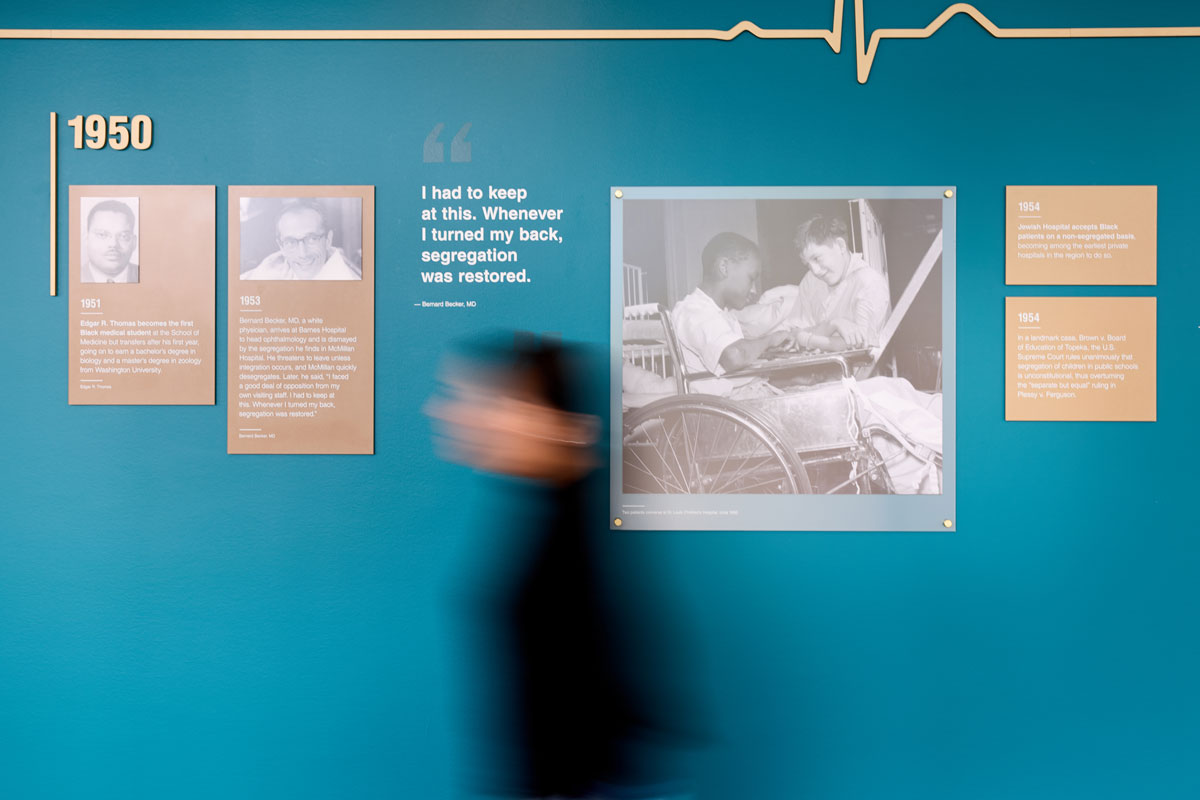

Individuals who took stands against racial injustices also are featured prominently. In the 1950s, for instance, Bernard Becker, MD, came to WashU Medicine to head its ophthalmology department and was troubled by the segregation he witnessed in McMillan Hospital on the Medical Campus. Becker, who was white, threatened to leave unless integration occurred. It did. Today, the School of Medicine’s medical library is named in his honor.

The timeline also recounts how, in the early 1960s, medical students, in a statement against segregation, rearranged beds in a segregated ward of Barnes Hospital so that Black and white patients would not be separated based on race.

Matt Miller

Matt MillerAnd former WashU Medicine faculty member Bernard Jaffe, MD, recalled an incident that occurred in 1964, when he was an intern at Barnes Hospital and training with revered WashU Medicine surgeon Eugene Bricker, MD. “He had a patient — a white man — who was scheduled for an operation. The patient said, ‘I’m not willing to be in this room with that person,’ pointing at the African American man in the other bed. ‘I’m not used to sharing a room with a Negro.’

“Dr. Bricker said, ‘You know, you’re absolutely right. You need a new room; in fact, you need a new hospital, and a new surgeon. I’ll call your referring doctor and tell him.’ He might as well have said that over the loudspeaker. It was astonishing because in those days there were testy moments. But Dr. Bricker was God, and as soon as he said that, integration was accomplished.”

The exhibit also features Black nurses at Barnes Hospital, including Velma Jones, who in 1949 became the first Black nurse to head a nursing division; and head nurse Dorinda Harmon, who in 1968 established a prenatal course for expecting parents. The course was the first of its kind at the hospital.

A photo from more recent times depicts Medical Campus health-care workers and students in a “White Coats for Black Lives” demonstration in 2020, shortly after police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, a Black man. Institutional efforts to combat racial injustices also are highlighted, such as WashU Medicine’s “Commitment to Anti-Racism” statement issued in 2021. The statement articulates the school’s intent to address any systemic disparities across its missions of education, research and patient care.

The exhibit’s roots stretch back to 1990, when then-faculty member Edwin McCleskey, PhD, and then-students James Carter and William Geideman began interviewing people who had played roles in the desegregation of the medical school and its affiliated hospitals (Carter and Geideman received their medical degrees in 1993). These oral histories, available in the Bernard Becker Medical Library’s archives, contribute to the timeline’s content. The offices of diversity, equity and inclusion at WashU Medicine and BJC helped to advance the project.

“While we are witnessing efforts to suppress or whitewash history across the country, we are deliberately transparent about our history,” said Sherree A. Wilson, PhD, the medical school’s associate vice chancellor and associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion. “Viewers will learn about the experiences of Black people and the upstanders who took action against racial injustice. We have made great strides toward our goal of creating a more inclusive environment on the Medical Campus, and we acknowledge that there is still more work to do.”

Matt Miller

Matt MillerSince 2017, WashU Medicine has increased the number of faculty from populations historically underrepresented in medicine and research by 82%, from 118 to 215. And among first-year medical students, 30% of the entering class of 2023 are from populations underrepresented in medicine, double the percentage of such students who entered medical school in 2017.

Beyond the physical installation, WashU Medicine and BJC plan to use the desegregation wall as a tool in diversity, equity and inclusion programming for employees and as part of the curriculum for students.

“The wall is a permanent reminder of what we’re committed to in our mission to provide exceptional care,” said Steven Player, PharmD, vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion at BJC HealthCare. “Nationwide, the health-care industry, including institutions such as Barnes-Jewish Hospital, Children’s Hospital and WashU Medicine, has historically failed to provide equitable care. These actions, both intentional and unintentional, have contributed to significant and pervasive health disparities. It’s time for us to acknowledge this and play a role in our region’s truth, reconciliation and healing process.”

Richard J. Stanton, the School of Medicine’s vice chancellor of administration and finance, noted the wall serves as a daily reminder of the Medical Campus’ commitment to racial equity across all missions. “The university and our affiliated hospitals have a history that doesn’t reflect who we want to be today. The exhibit makes a statement that we own our history, we own our present, and we will own our future.”

Matt Miller

Matt Miller