Neurofibromatosis (NF) Center provides patient care and support, seeks solutions

Washington University’s Neurofibromatosis (NF) Center focuses on research and patient care for individuals affected by NF, a complex genetic disorder

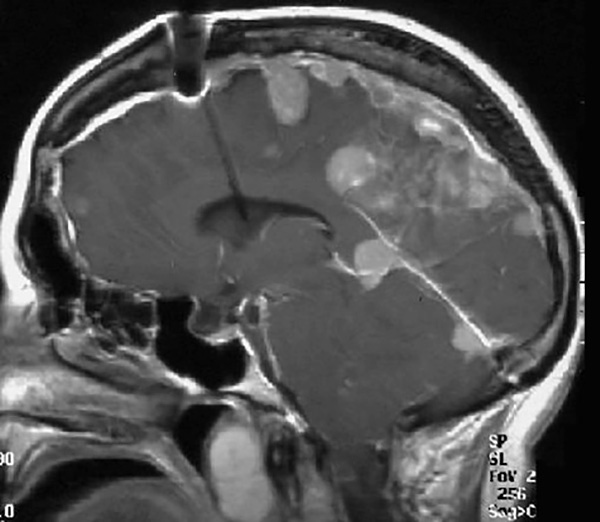

Meningioma tumors in the brain of a neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) patient.

A diagnosis of neurofibromatosis (NF) brings many uncertainties to the lives of children and their parents. NF comprises a set of three complex genetic disorders (NF1, NF2 and schwannomatosis) that can affect almost every organ system, causing a predisposition for tumors to grow on nerves in the brain and throughout the body.

There are no cures for these conditions, and few effective treatments are available.

Of the three forms of NF, NF1 is the most common, affecting 1 in 2500 individuals worldwide. People affected with NF1 are prone to developing both benign and malignant tumors as well as learning and attention impairments, reduced physical coordination, seizures, headaches, scoliosis, bone deformities and cardiovascular problems.

To better understand NF and related conditions and to help patients and their families manage and cope with the disorders, David Gutmann, MD, PhD, the Donald O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology, established the Washington University Neurofibromatosis (NF) Center in 2004.

The NF Center is composed of clinicians and scientists focused on accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and its application to patient care. The center delivers comprehensive, multidisciplinary care at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, facilitates basic and clinical research, and provides resources and activities for affected individuals and their families.

Although principally an inherited condition caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene, some people may spontaneously develop an NF1 gene mutation, and become the first in their families with NF1. To diagnose the condition, physicians consult a list of clinical features. The presence of two or more of these signs confirms a diagnosis of NF1.

According to Gutmann, the identification of the NF1 gene in 1990 ushered in an exciting new era of clinical care and research. Using this information, Gutmann and others were able to better understand how the NF1 protein (neurofibromin) functions in health and in people with NF1, generate accurate small-animal models of NF1-related medical problems, and find new treatments.

NF Center research

In mouse models of NF1, Gutmann and his scientific collaborators have made a number of important discoveries about what he calls the “tumor ecosystem.”

“Like organisms in a jungle or another ecosystem, tumor cells only flourish when they can acquire the resources they need from their environment,” he explained. “Access to these resources is not only influenced by the inherent abilities of the cells that become tumors, but also by the non-cancerous cells in their neighborhood.”

For example, Gutmann’s research has shown that microglia cells, which normally support and protect healthy brain cells, can also provide essential aid to optic gliomas, one of the most common brain tumors affecting children with NF1. Insights into these forms of assistance may provide future targets for tumor treatments.

In 2004, work from the NF Center resulted in the discovery of a new treatment for brain and nerve tumors in people with NF1. Gutmann and his colleague Jason Weber, PhD, associate professor of medicine, found that a protein called the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) was overactive in tumors from mice and people with NF1. This led to the realization that rapamycin, which inhibits mTOR function, was a logical therapy in NF1.

Another major research focus is discovering why people with NF1 develop learning impairments and behavior problems.

“While one of our top priorities is halting tumor growth, it’s also important to ensure that these children don’t have the added challenges of living with learning and behavioral issues,” Gutmann said.

Gutmann and his colleagues have shown that there are lower brain levels of dopamine in a mouse model of the disease; dopamine-producing nerve cells in the mice had shorter branches, leading to missed connections and reduced dopamine supply in brain regions, such as the hippocampus, which makes important contributions to long-term memory formation.

The finding that dopamine was responsible for memory and attention function in mice provided a scientific explanation for why medicines like Ritalin work in children with NF1-related attention deficits.

New initiatives in the NF Center are focused on understanding the variability of clinical problems in people with NF1. These differences are generated by several factors, including varying forms of the NF1 mutation, other genomic influences and environmental causes.

To determine how these factors impact people with NF1, Gutmann and his colleagues have established the NF1 Genome Project, NF1 Patient Registry Initiative, and NF1 Brain Trust programs. In addition, they are working to generate mice with the identical NF1 gene changes seen in people with NF1 as a first step towards personalized medicine.

Multidisciplinary clinical care

Gutmann and a team of specialists care for people with NF in the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Program at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Children and adults seen in the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Program undergo a series of specialized assessments to identify problems early. Working with St. Louis Children’s nurse practitioner Anne C. Albers, MSN, and Washington University physical therapist Courtney M. Dunn, DPT, Gutmann and his team have integrated research into clinical practice to fuel development of new treatments.

Gutmann, Michael Chicoine, MD, August A. Busch Distinguished Professor of Neurosurgery, and Timothy Hullar, MD, Washington University otolaryngologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and St. Louis Children’s, also care for people affected with NF2, a much rarer disorder. People with NF2, who are also treated at Barnes Jewish Hospital, are prone to development of several different types of nervous system tumors and often lose their hearing as a result of brain tumors.

The NF Clinical Program is also a member of the NF Clinical Trials Consortium, which provides affected individuals opportunities to participate in clinical trials.

Patient and family support

Beyond its clinical care and research efforts, the NF Center is focused on empowering families. Its website features many resources; children and their families also can join Club NF, a free bimonthly play-based therapy group for kids in kindergarten through eighth grade. These events, supported by the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation, engage children in innovative activities designed to help them practice and improve skills that can be impaired in NF1.

“Our overall mission is to galvanize and promote research on NF, achieving significant and meaningful breakthroughs in the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions,” Gutmann said. “We believe that this is possible when researchers, medical professionals and families partner together.”

For more information about the center and its services, please visit nfcenter.wustl.edu.