NIH grant to fund radiation oncology center on Medical Campus

School named part of national network focused on biology of irradiated tumors

Matt Miller

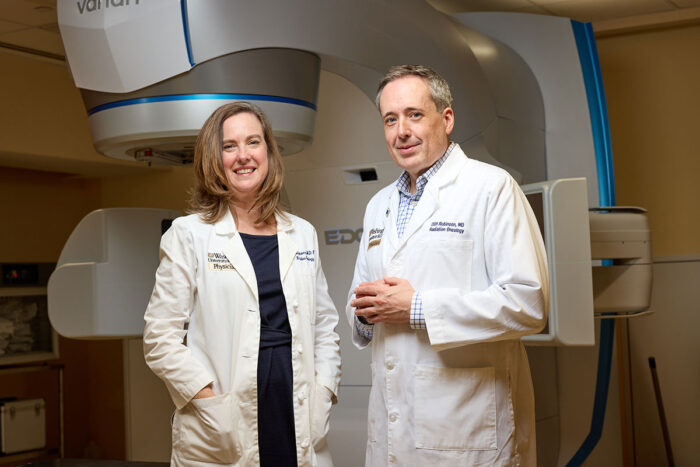

Matt MillerJulie K. Schwarz, MD, PhD, (left) and Clifford G. Robinson, MD, both at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, are leading a new radiation oncology research center focused on understanding the biologic effects of radiation therapy in cancer treatment. It is one of only five centers that make up the Radiation Oncology-Biology Integration Network, of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has received a five-year, $7.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to support a radiation oncology center that is part of a select national network of centers aimed at understanding the biologic effects of radiation therapy in cancer treatment.

Washington University’s new center — named the MicroEnvironment and Tumor Effects of Radiotherapy Center (METEOR) — is to be co-led by Julie K. Schwarz, MD, PhD, and Clifford G. Robinson, MD, professors of radiation oncology at the School of Medicine. It is one of only five centers that make up the NIH’s Radiation Oncology-Biology Integration Network.

Researchers within Washington University’s center will investigate how radiation therapy influences immune cells, immune signaling and tumor metabolism in the microenvironment of the tumor in patients with pancreatic and cervical cancer. Schwarz and Robinson treat patients at Siteman Cancer Center, based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

“We are focused on pancreatic and cervical cancer because they are extremely hard to treat, and there’s a real opportunity for improvement,” said Schwarz, who is also director of the Cancer Biology Division and vice chair for research in the Department of Radiation Oncology. “We need a better understanding of what radiation therapy does to the immune system. At times, radiation can stimulate the immune system. And at other times, radiotherapy can suppress it. We don’t understand what makes it go in one direction or the other. These national centers are designed to help us answer these kinds of questions.”

The university center’s scientists will analyze biological samples and tumor images collected from patients who choose to participate in the research. The investigators will collect samples over time — before, during and after treatment — to help understand the biology of the original tumor and surrounding immune cells and how these change after receiving prescribed standard courses of radiation and chemotherapy.

According to the researchers, most of the samples and imaging gathered on each patient will be collected during standard care, in an effort to reduce additional burdens on participants. The investigators will follow patients over time and study any tumors that may recur. Much research into immunity in cancer is focused on T cells. Similarly, the researchers will investigate T cells, but they also will include less studied cell types, including macrophages and dendritic cells.

“This network of centers is bringing together national leaders in the field to analyze, in a detailed and comprehensive way, what radiation is actually doing to cancer cells and their surroundings, including to the immune cells that are present,” said Robinson, who also leads the Cardiothoracic and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy services and serves as the radiation oncology department’s associate director of clinical programs. “We will be able to share what we learn across all of the centers. We’re also excited about the training component of our center; it’s so important to be able to prepare the next generation of investigators to carry this work forward.”

Matt Miller

Matt MillerThe network’s research will help investigators get to the bottom of fundamental, long-unanswered questions in the field of radiation oncology. The researchers will be able to compare the effects of various treatment regimens — including chemotherapy alone, radiation alone, and combined chemo-radiotherapy — as well as different types of radiation, such as external beam radiation versus brachytherapy, in which a radiation source is placed inside the body, as close to the tumor as possible.

The researchers also will work to understand differences that occur when the same radiation dose is delivered in different fractions. For example, some patients receive fewer treatments with a higher radiation level delivered in each treatment, while others receive more treatments with less radiation delivered in each. The researchers will be able to harness advanced single-cell sequencing technologies and tools for mapping the 3D structure of the tumors to identify, in great detail, what individual cells are doing before, during and after these treatment strategies.

“The goal of gathering all of this data is to help us identify possible treatment targets and design future clinical trials based on what we learn about the function of these cancer cells and nearby immune cells,” Schwarz said.

Other co-principal investigators of the university’s center are David G. DeNardo, PhD, a professor of medicine and co-director of the Section of Molecular Oncology in the Division of Oncology; Geoffrey D. Hugo, PhD, a professor of radiation oncology and vice chair of medical physics; Albert M. Lai, PhD, a professor of medicine and deputy director of the university’s Institute for Informatics, Data Science and Biostatistics; and Michael Benjamin Major, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Professor of Cell Biology & Physiology.