Q & A: Ebola – What you need to know

Washington University infectious disease specialist Steven Lawrence, MD, answers questions about the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa

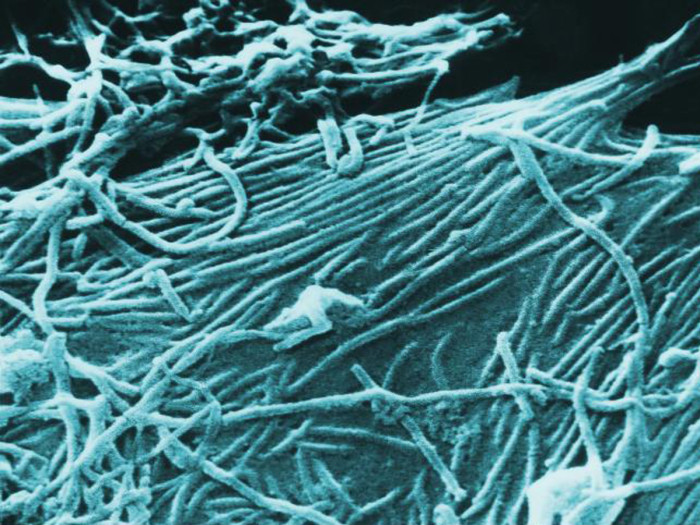

First discovered in 1976 in central Africa, Ebola is an infectious virus that can cause severe, often fatal illness in humans. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / Cynthia Goldsmith.

Updated: October 17, 2014

Washington University infectious disease specialist Steven Lawrence, MD, answers questions about the Ebola virus and its potential to spread.

How is Ebola spread?

Ebola is not easily transmitted, and people are only infectious if they have symptoms. There is no risk of transmitting the virus by people who have been exposed to Ebola but do not yet have symptoms. Unlike the flu and other respiratory infections, the virus does not spread through the air. To become infected, you must have direct contact with the body fluids (blood, sweat, stool, etc.) of another infected individual. People (or animals) who are sick with Ebola shed large quantities of the virus in their body fluids. To cause infection, those fluids, or objects such as needles contaminated with those fluids, must come in direct contact with an individual’s mucus membranes – eyes, nose, mouth – or a cut in the skin. Nearly all cases of Ebola have occurred among health-care workers or family members who have provided direct care to sick patients without appropriate infection-prevention procedures, and those who have come into contact with the bodies of people or animals who have died from Ebola.

What are the symptoms of Ebola?

Symptoms of Ebola may include:

- High fever

- Headache

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Muscle pain

- Weakness

Symptoms can appear anytime from two to 21 days after exposure. Complications from the virus include organ failure, severe bleeding, seizures and coma. Death occurs in 50 to 90 percent of patients with Ebola, with the chances of survival greater when patients receive aggressive care.

How likely is it that Ebola will become an epidemic in the U.S.?

In a prolonged and large outbreak, sporadic cases of Ebola could occur in the U.S. and we have seen that recently in Texas where two nurses have been diagnosed with the disease. However, it is extremely unlikely that any imported cases from people traveling here with active infections would lead to a widespread epidemic. At Washington University Medical Center, we are on high alert for patients with fevers who have traveled recently to or from West Africa. In addition, for those who do not have symptoms but may have been exposed to the virus, we would implement routine temperature checks with immediate isolation and testing if a fever develops within 21 days from exposure.

What if sporadic cases end up in the St. Louis region?

Washington University has extensive expertise in infection control and prevention. Our clinicians are trained to recognize cases of Ebola. We also have surveillance systems and protocols in place to manage any suspected cases. If we were to identify any cases here, we would isolate individuals suspected of being infected to prevent exposing other people in the hospital. Health-care staff would wear special protective equipment to prevent transmission. Unlike many rural African areas, where the outbreak has hit hardest, we have all the necessary resources at our disposal.

How is Ebola treated?

To treat patients with Ebola, health-care workers provide supportive care, which can involve close monitoring, support of failing organs and giving fluids or blood transfusions. There are no approved medications to directly treat Ebola virus; however, researchers are investigating drugs that are in various stages of development. There is no approved vaccine for Ebola, thus infection prevention depends on avoiding exposure to body fluids from infected patients using well-established and effective protocols.

Where did Ebola come from?

Ebola first was reported in 1976 in central Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River. Since then, there have been smaller periodic outbreaks throughout Africa. The current outbreak in West Africa is by far the largest on record. No human cases or deaths have ever been reported in the U.S. While Ebola causes severe disease in humans and primates, its natural reservoir is thought to be small mammals, possibly bats.

How does Ebola compare to other outbreaks such as the flu?

The current Ebola outbreak in West Africa is a major public health emergency in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia that is requiring a rapid and robust response to contain it. There are many factors somewhat unique to West Africa, including a lack of adequate health-care facilities and supplies; a lack of education about the disease and its transmission; distrust of the health-care providers there to help; and traditional burial practices that involve direct contact with the body. These factors have combined to make this the worst Ebola outbreak in history. But to put the risk to our region into context, it is important to remember that more common infectious diseases pose a more predictable, more tangible and greater danger to the general public. For example, last year’s flu season was one of the most severe in terms of deaths in younger adults in the St. Louis area. While Ebola strikes more fear and generates more attention than the flu because of the dramatic illness it causes, flu is a much greater public health concern for our region.

Steven J. Lawrence, MD, is a Washington University infectious disease specialist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. His research focuses on human immune response to viral infections and vaccines, the epidemiology of infections and emergency preparedness.

Read more about Ebola

- New research at Washington University School of Medicine provides insight into one mechanism the virus uses to evade the immune system.

- Summary from the World Health Organization’s site

- Summary from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s site

- Perspective from the New England Journal of Medicine about Ebola by Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Ebola Preparedness at Washington University

Read travel recommendations and Ebola preparedness protocols for the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital communities.