Researchers find innovative ways to combat world’s deadliest bacteria

Khader, Philips, Stallings developing new therapeutics, vaccines for tuberculosis

Matt Miller

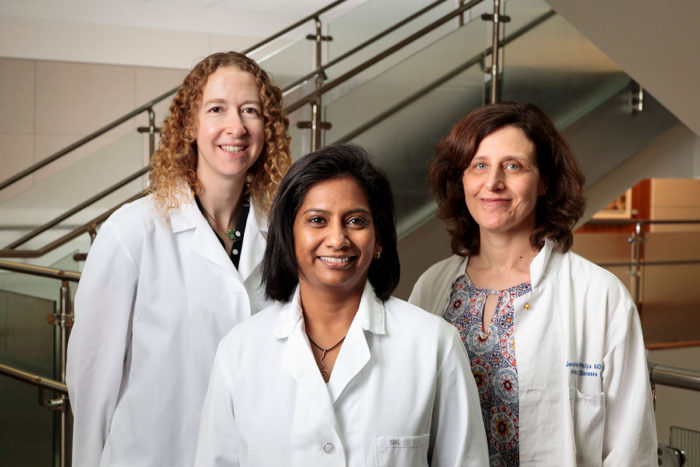

Matt MillerThree of the most innovative scientists in the field of tuberculosis research call Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis their professional home. From the left, Christina Stallings, PhD, Shabaana Abdul Khader, PhD, and Jennifer Philips, MD, PhD, are on the front lines of the battle to stop the world's deadliest bacteria.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death worldwide from infectious disease. About 2 billion people are infected with the bacteria that cause TB, and just under 2 million die from it every year. In the wealthy nations that fund most biomedical research, though, TB is rare – the U.S. reported fewer than 10,000 cases in 2016 – so the deadly disease doesn’t garner as many scientific studies as other major threats to human health.

Among researchers studying TB, three of the most innovative are at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Shabaana Abdul Khader, PhD, Jennifer Philips, MD, PhD, and Christina Stallings, PhD, each hold several patents on new ways to prevent or treat TB. Although the three take different approaches to studying this important but oft-overlooked disease, working nearby one another opens up possibilities for close and productive collaborations.

“It is unusual to have three strong TB labs in the same place,” Khader said. “It’s amazing to be able to just walk down the hall and talk over a problem with colleagues. WashU is a very collegial and collaborative institution. We are engaged in multiple partnerships, and we find them productive and fulfilling.”

Khader, a professor and interim head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology, is working to develop vaccines against TB. The current TB vaccine is only modestly effective, not because it elicits an immune response that is too weak, but because it is too slow. In people vaccinated against TB and later infected with the bacteria, activation of immune cells is delayed, allowing the bacteria to multiply.

Also a professor of pathology and immunology, Khader is the primary holder of two patents for TB vaccine candidates. Unlike the current TB vaccine, which is injected, both vaccine candidates are designed to be inhaled through the nose. By delivering vaccines in the same way that people naturally would be infected with the TB bacteria, Khader hopes to trigger a more robust immune response. Khader also holds a third patent for a platform to screen potential vaccine candidates. This platform will speed up the process of identifying the most promising options to move forward into clinical trials.

Philips, an associate professor of medicine and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Department of Medicine, studies how the TB bacterium evades the body’s immune defenses. With Phyllis Hanson, MD, PhD, the Gerty T. Cori Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology, Philips has a paper in press at the journal mBio that explains how TB bacteria disarm white blood cells. These immune cells typically destroy invading microbes by engulfing them, herding them into a special organelle inside the cells, and then killing them with a barrage of toxic molecules. TB bacteria escape destruction by rupturing the bacteria-killing organelles. Philips and Hanson showed that the bacteria obstruct the cells’ attempts to repair the organelles, effectively disarming the immune cells and converting the body’s defenders into safe havens to live and multiply.

Philips, who is also a professor of molecular microbiology, holds two patents related to enhancing the ability of immune cells to fight the TB bacteria. Shoring up the body’s defenses, rather than killing the bacteria directly with antibiotics, is one way to get around the growing problem of antibiotic-resistant TB bacteria. One patent describes a technology for packaging compounds that target human genes. The packaging protects the compounds and directs them to the correct cell. The other patent is for a drug that shuts down a human metabolic pathway that TB bacteria subvert for their own benefit. Turning off the pathway does not harm people but makes it harder for the bacteria to multiply.

Stallings, an associate professor of molecular microbiology, focuses on understanding how TB bacteria cause disease with a goal of developing better drugs. Currently, people are treated with a combination of four antibiotics given repeatedly over six months. It is difficult for many people to adhere to such a long and complex regimen, and if they fail, their disease is likely to return. Stallings studies how TB bacteria defend against assault by immune cells and antibiotics so they can persist in a person’s body, often for decades. She has discovered that the bacteria produce certain proteins to shield themselves, and interfering with these bacterial defenses can help treat disease. Stallings has three patents related to targeting TB bacteria. Two are designed to enhance the effectiveness of antibiotics already used for treating TB by interfering with the bacteria’s ability to withstand stress. The third describes a new potential antibiotic for TB that also targets the bacteria’s stress response.