Schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders focus of new clinic for teens, young adults

Clinic services provided free of charge

Matt Miller

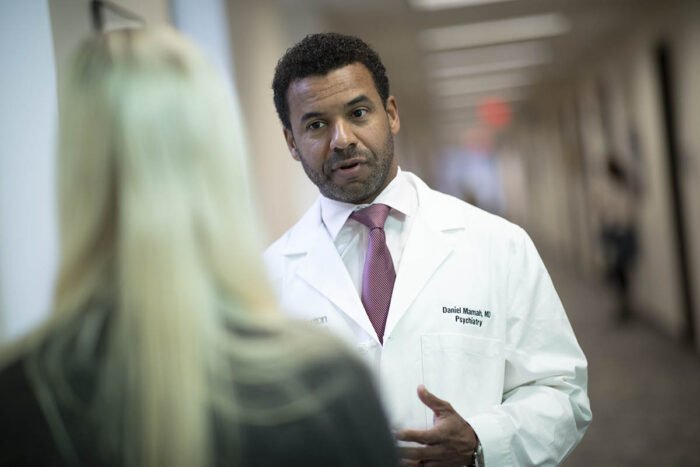

Matt MillerDaniel Mamah, MD, is the clinical director of the Washington University Early Recognition Center, a clinic for teens and young adults at high risk for psychotic disorders.

The first signs of mental illness involving psychosis — the experience of having hallucinations, delusions or intrusive, disturbing thoughts — often appear during the teen years. There is emerging evidence, however, that early intervention can help such adolescents avoid the extremely serious problems that can derail their educations and disrupt family relationships.

With this goal in mind, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has opened a clinic to provide treatment free of charge to adolescents and young adults who may be in the early stages of psychosis. Mental health professionals at the new clinic will treat people ages 13 to 25 at high risk for developing psychosis, as well as those who have been diagnosed with a psychotic illness within the prior three years.

Psychosis is a symptom of psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and some forms of bipolar disorder. Such illnesses affect an estimated 3% of the U.S. population, according to Daniel Mamah, MD, director of the new clinic, called the Washington Early Recognition Center (WERC).

The new clinic began seeing its first such patients earlier this year. Mamah, an associate professor of psychiatry, has directed a research effort with the same name for the last few years. Those treated at the clinic will be offered the opportunity to participate in research studies, but the new clinic is primarily aimed at providing early treatment to adolescents and young adults experiencing psychosis.

“There is a real need to help young patients and their families because psychotic disorders tend to get worse over time, especially if untreated,” Mamah said. “The aim of this clinic is to get patients into treatment as early as possible, providing them with interventions such as individual psychotherapy, family therapy and medication. Like most other illnesses, the earlier you intervene with psychosis, the better the long-term outcomes tend to be.”

Similar clinics that attempt to treat young people with psychosis before or when most symptoms appear have opened in larger cities, mainly on the East and West coasts, but this new clinic is the only one of its kind in the St. Louis region. Mamah and a staff of psychotherapists and social workers will counsel and treat affected youth at 4444 Forest Park Ave. Patients also will undergo detailed behavioral and cognitive assessments using structured interviews and questionnaires. During the current COVID-19 outbreak, visits are being conducted using telemedicine to assess and serve patients.

Mamah said that early treatment makes it possible to delay or perhaps even prevent the onset of some of the most serious problems associated with psychotic disorders, such as hearing voices and seeing things that aren’t there. The earlier treatment also may help young people avoid extended hospitalizations that can be necessary to get severe psychosis under control.

“There are a number of signs that someone is at risk of developing psychosis, but those signs can be dismissed as typical teenage behavior,” he said. “Perhaps your child used to be very outgoing but is now withdrawn. Or he or she is not doing as well in school as in the past. Sometimes a person will seem to respond to voices that no one else hears or will become more suspicious. These kinds of behavioral changes may be chalked up to adolescent changes, but they usually are fairly apparent to family members.”

When psychosis goes untreated, those affected by the condition not only may suffer from symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions, they may struggle to stay in school or succeed in careers.

In Missouri alone, the total economic burden for individuals with schizophrenia is about $2 billion annually, according to the Missouri Department of Mental Health. That estimate factors in lost wages, criminal justice system-related costs, and hospitalizations. The average hospital stay for a patient with schizophrenia is seven days, longer than average stays for those who have kidney transplants, heart attacks or hip-replacement surgeries.

“It’s a serious public health issue,” Mamah said. “But because of stigmas that remain attached to psychiatric illness, many patients go months or even years without receiving treatment that could help them.”

Cost won’t be an issue at the clinic. With grant support from the St. Louis County Children’s Service Fund, The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation, patients ages 13 to 25 will be able to receive psychiatric treatment free of charge, regardless of whether they have insurance. If medications are needed, however, there will be costs associated with those.

Individuals who might need help may be referred to the clinic by parents, guardians, pediatricians or other adults in their lives. The team at the clinic then will do a screening by phone to see whether a patient is actually exhibiting signs of the risky behavior connected to psychosis, such as hallucinations, delusions and disordered thinking.

The clinic team then may recommend a more detailed evaluation to see whether the individual is eligible to be treated at the clinic. Teens with significant intellectual disability, for example, would not be candidates for treatment.

“When people contact us, we’ll ask them some questions and, if needed, ask them to come to the clinic for a more detailed assessment,” Mamah said.

Because of funding limitations, people over age 25 aren’t eligible for treatment at the clinic. However, Mamah and his colleagues are pursuing further grants in hopes of being able to offer treatment to more young people in the St. Louis area.

For more information, call 314-362-6952 or check the website at werc.wustl.edu.