Stressed? There’s an app for that

Washington University-based team launches stress-management app

Robert Boston

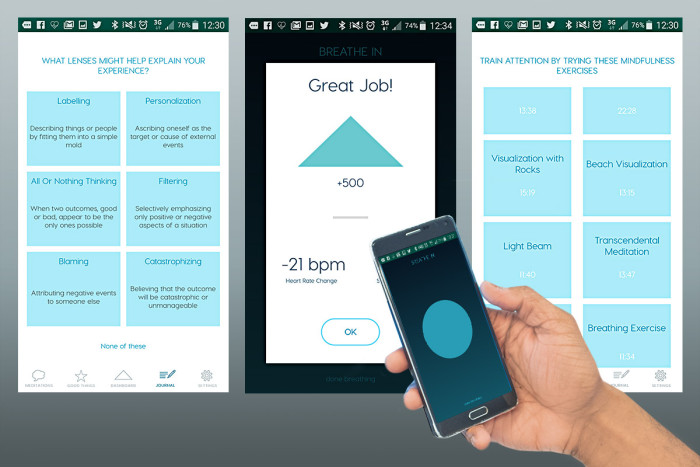

Robert BostonMD/PhD student Ravi Chacko demonstrates the Mindset app, which he and a team of other medical and engineering students at Washington University in St. Louis created as an aid to veterans and others experiencing stress. The app measures a user’s stress and suggests steps to take to alleviate it.

After learning that local veterans were facing long waits for mental health services, a team of medical and engineering students at Washington University in St. Louis wanted to help in some way.

The team created what its members hope will be an aid to veterans and others experiencing stress: an app that measures a user’s stress and suggests steps to take to alleviate it.

MD/PhD student Ravi Chacko and biomedical engineering graduate Elizabeth Russell threw themselves into converting a good idea into a marketable product. They co-founded a company, obtained $250,000 in funding from private investors and brought social worker Cara Jacobsen, a Saint Louis University alumna, on board to direct clinical operations. The app, called Mindset, is now available for Android and in beta testing for iOS.

“We found there weren’t many tools that disseminated evidence-based exercises for mental health,” Chacko said. “So we decided to build something that gets to know you better, using your heart rate and your data, and then suggests when to do a helpful exercise to alleviate stress.”

The team learned this month that Mindset is a finalist in the App Idea Awards, a national competition in which the winner receives $70,000 in app development and design.

The team, originally made up of six students, formed as part of IDEA Labs, a student-driven bioengineering design and entrepreneurship incubator that works in partnership with the Schools of Medicine and of Engineering & Applied Science, and the Skandalaris Center for Interdisciplinary Innovation and Entrepreneurship. IDEA Labs provides resources, training and mentorship to students working on biotechnological solutions to clinical problems.

The app uses information from a heart-rate monitor to measure a user’s stress. When stress markers begin to rise, the person’s phone beeps, and a notification pops up.

“Your heart rate is activating,” it reads. “How do you feel?”

The user taps an icon reflecting his or her mood — glad, mad, sad or stressed — and types a sentence or two of explanation. In response, the app suggests appropriate exercises such as meditation, gratitude journaling, or cognitive-behavioral therapy activities.

To demonstrate the app, Chacko chose a controlled-breathing exercise. A blue circle slowly expanded for four beats, then contracted. And again: expand, contract, expand, contract.

Peering intently at his phone, Chacko breathed in and out, in sync with the circle, then tapped his screen.

“My heart rate is down by 14 beats per minute, stress down 27 percent,” he reads. “Just those three breaths had an effect.”

“These exercises are modeled on the ones a therapist would have you do in the office,” said Jacobsen, who — along with Chacko and an advisory board of psychiatrists and psychotherapists, including three Washington University faculty members — combed psychotherapy literature to ensure that activities suggested by the app are based on sound science.

Now that the app is built, the Mindset team is busy making sure it is effective.

“We’re testing it on medical students at Saint Louis University now,” Chacko said. Student volunteers were divided into two groups, with half receiving the app and a wearable heart-rate monitor for the first six weeks of the study and the other half for the second six weeks. The study is measuring the effect of app usage on self-reported stress, as well as whether usage drops off over time.

“We may even see an effect on academic performance,” Chacko said. The students will be taking a national, standardized test for second-year medical students at the end of this year, “so we will be able to compare test scores of those who used the app with those who didn’t,” he said.

The medical students are using the most current version of Mindset, which is designed only for stress relief. Over the long term, though, the Mindset team plans to use the app to supplement mental health treatment.

“We don’t want or expect to replace psychiatrists,’” said Chacko. “We’re looking at this as an adjunct to traditional treatment, not a replacement.”

The team eventually would like patients to use the app to help manage negative emotions and send data such as the frequency and triggers of such emotions to their physicians. Doctors then would use this detailed, individualized information to tailor treatment plans.

“We have been talking with mental health professionals, and they are very interested in getting this kind of data,” said Russell. “We would provide an option for the user to share it.”

For the time being, though, the app is all about stress management, Chacko said.

To illustrate the kind of stressful experiences Mindset is designed to address, Chacko recounted a frustrating personal encounter from years before. As he finished, his phone buzzed in his pocket. “See, I’m getting upset just thinking about it,” he said. “And the app knows.”

Illustration by Eric Young

Illustration by Eric Young