Students, faculty providing coronavirus-related outreach to Latino population

Spanish-speaking students, faculty partner with community leaders to offer education aimed at preventing virus’ spread

Huy Mach

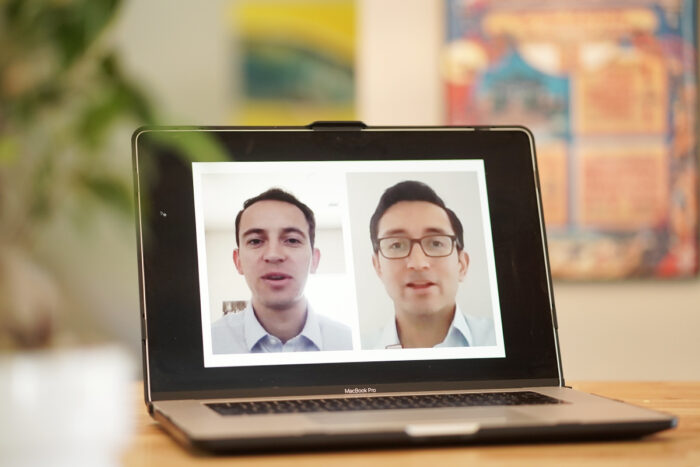

Huy MachZach Jaeger (left), a third-year medical student at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Carlos Mejia, MD, an instructor in medicine in the university’s Division of Infectious Diseases, connect via Zoom to brainstorm ideas for reaching St. Louis’ Spanish-speaking communities regarding COVID-19 prevention.

As stay-at-home orders to stem the spread of COVID-19 were announced in March, Austin Ibele, a first-year student at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, investigated whether information about the coronavirus existed in Spanish to alert the area’s Latino population.

Ibele called COVID hotlines and found none with Spanish options. He scanned various local government and health department websites. Nothing.

Eventually, after scrolling several social media feeds, Ibele found a Spanish-language Facebook page named “STLJuntos,” which translates to “St. Louis Together.” Created in March, the newly formed page had just a few followers but offered updates on local stay-at-home mandates and links to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Spanish-language coronavirus page.

In less than a day, Ibele and other medical students had joined forces with the two women who had created STLJuntos. All shared the same urgency to expand COVID-19-related outreach and educate the region’s Spanish-speaking communities.

In less than a week, the medical students helped STLJuntos more than triple its number of Facebook followers. They facilitated partnerships between STLJuntos and Latino community activists, language translation services and advocacy groups, such as the International Institute, STL Mutual Aid and Casa de Salud. Together, they created and disseminated coronavirus information in Spanish via a hotline, pamphlets and social media content, including educational videos featuring the university’s Spanish-speaking faculty.

Across the Washington University Medical Campus, student and faculty volunteers have rallied to provide COVID-19 information to the region’s non-English speakers. Besides Spanish, students and faculty who speak Arabic and Bosnian also have mobilized to address language barriers.

“We knew we had to act quickly because of how fast the virus spreads once in the community,” Ibele said. “Health disparities exist during normal times, and these inequities are compounded when something new comes along like coronavirus. That’s why it’s extremely important to make sure all members of the public are educated.”

Throughout the U.S., underrepresented minorities living in low-income communities with limited access to health care represent a disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases and deaths. This is because social and economic conditions predispose them to higher rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart disease and other illnesses that aid the virus in weakening the body’s organs, said Laurie J. Punch, MD, an associate professor of surgery who treats patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

“It’s not surprising that brown and black people are getting sicker from COVID-19,” said Punch, who also is director of medical student community engagement at the medical school. “Those who do not speak English have the added risk of not having adequate access to hotlines, medical care and educational materials with language-appropriate communication in place.”

In late March, STLJuntos co-founder and community activist Lourdes Bailon was refinishing the staircase in her house while listening to news about the coronavirus. As soon as she heard about the region’s impending shelter-in-place orders, she halted the renovations indefinitely and, with her friend Gabriela Ramirez-Arellano, started the Facebook page and began organizing community outreach efforts.

“Native Spanish speakers are isolated from the larger community for lots of reasons, a major one being the Spanish language gap,” Bailon said. “I have no doubt that many would have been confused about the shelter-in-place orders if the Latino community hadn’t mobilized with Washington University’s medical school to disseminate information in Spanish.”

Data on coronavirus deaths is preliminary and, in about one-third of the cases, lacks information on patients’ race and ethnicity. However, as of early May, statistics from Missouri’s Department of Health & Senior Services and the U.S. Census Bureau showed that Latinos represent about 4% of the state’s population and 6% of the state’s deaths from COVID-19.

By comparison, Caucasians represent nearly 85% of the state’s population, but their coronavirus mortality rates hover around 2%.

“The discrepancy is not as easy to see as it is in New York, where the Latino population is much larger,” said Carlos Mejia, MD, an instructor in medicine in the university’s Division of Infectious Diseases. “But it still exists in Missouri. My concern is that the number is actually higher because many Latinos do not seek medical care because they fear incurring significant health-care costs or prosecution related to immigration.”

A native Spanish speaker originally from Guatemala, Mejia appears in student-produced, social media videos dispelling coronavirus misinformation. “A lot of the myths are rooted in the culture,” he said. “Home remedies are common. For example, most of us have family members claiming that if we drink tea with garlic and lemon, or gargle saltwater every 10 minutes, we will be protected from the virus. Although the remedies will not harm, they do not offer immunity.

“It’s important to hear this from a Latino doctor living in their community with similar values,” Mejia added. “It builds trust and reassures people that we’re all in this together. It shows that health-care workers can be allies. This is especially important in light of recent anti-immigration rhetoric.”

As a Mexican-born immigrant, Dayana Hernandez Calderon said she can relate to frustrations at the lack of reliable resources available to Spanish-speaking community members. “I’m excited to be a part of a project that helps close these gaps,” said the third-year medical student, who is a member of the university’s Latino Medical Student Association. “Public health policies are important for protecting vulnerable populations and ensuring there are enough resources available. For these policies to work, the entire community must adhere to them. We have a duty to provide culturally sensitive information that reaches the intended communities.”

Medical faculty and staff also have helped the Latino community understand the importance of social distancing, a counterintuitive concept in a culture that values extended family above all else. “They have helped the community understand that social distancing keeps them safe,” said Melissa Tepe, MD, vice president and chief medical officer for Affinia Healthcare, a St. Louis-area community health center that has a longtime partnership with the School of Medicine. “And that by social distancing, it’s not that we do not care about our family, but that to best care for them, it may be over the phone.”

Social distancing can be especially difficult when larger families live together, rely on public transportation and work at essential jobs that may not permit social distancing.

“To work through these scenarios in a nonjudgmental fashion is critical,” Tepe said. “The medical school is helping to ensure that our non-English speaking communities are getting factual COVID information in a manner that the people can understand.”

Zach Jaeger, a third-year medical student, said a grassroots approach to reaching the Latino community appeals to non-English speakers. “People are more likely to trust people with similar backgrounds,” he said.

“Prevention is a major yet undervalued pillar of medicine,” said Jaeger, also the community affairs chair of the Latino Medical Student Association Midwest Region. “Without effective treatments or a vaccine for the virus, public health policies remain the best way to decrease the number of COVID-19 cases and the number of deaths. As leaders during this pandemic, we have a responsibility to educate the community.”