Study uncovers hard-to-detect cancer mutations

Findings could help identify patients who would benefit from existing drugs

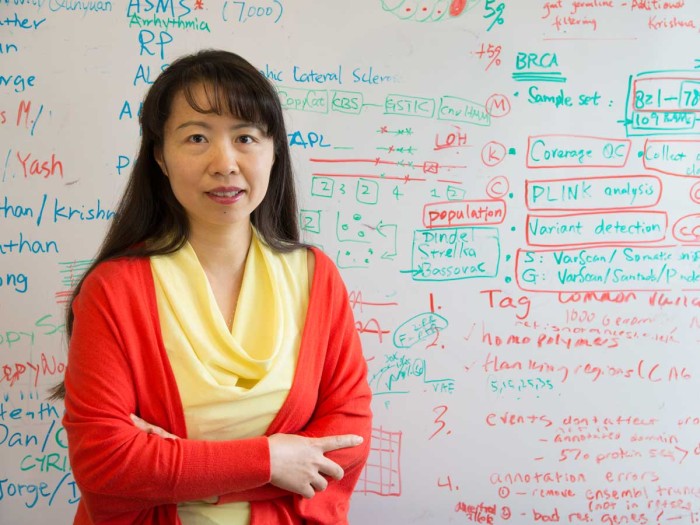

A new study led by Li Ding, PhD, describes a way to identify a complex type of mutation in cancer genomes that is systematically missed by current genetic sequencing tools. The analysis may expand the number of cancer patients who can benefit from existing drugs. <em>Photo: Robert Boston</em>

New research shows that current approaches to genome analysis systematically miss detecting a certain type of complex mutation in cancer patients’ tumors. Further, a significant percentage of these complex mutations are found in well-known cancer genes that could be targeted by existing drugs, potentially expanding the number of cancer patients who may benefit.

The study, from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, appears Dec. 14 in the journal Nature Medicine.

“The idea of not catching a targetable mutation in a patient’s tumor is devastating,” said senior author Li Ding, PhD, associate professor of medicine and assistant director of the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University. “We developed a software tool for finding a certain type of genetic error that has been consistently missed by cancer genome studies. We identified a large number of such events in critical cancer genes. The ability to discover such events is crucial for cancer research and for clinical practice.”

Mutations in the genome happen in a variety of ways. Perhaps the simplest is a change in a single “letter” of the DNA code. Among the more complex types of mutations are those that involve deleting or inserting a few letters. In the new study of 8,000 cancer cases, the investigators focused on mutations involving letters that are inserted at the same time that other letters are deleted.

“We call this type of mutation a complex indel because insertion and deletion is happening at the same time, in the same genomic location,” said Ding, who also is a research member of the Siteman Cancer Center at the School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “It is very difficult to capture such events because conventional approaches were designed to catch one or the other, not both types at the same time and place.”

To find the complex indels, the researchers developed specialized computer software and verified its accuracy in genome sequences into which they purposely introduced these complex mutations.

Then, the researchers looked at cancer genomes that already had been sequenced and found 285 complex indels in genes known to be associated with cancer. About 81 percent of these complex indel events had been missed on the first analysis using conventional approaches. And another 18 percent had been misidentified as some other type of mutation.

Ding emphasized the importance of developing special tools to find these complex indels, as the data suggest they go almost completely undetected by existing tools and appear to cluster in important cancer genes more often than can be attributed to random chance. This information is particularly valuable when indels are found in genes that already have drugs designed to counter the effects of mutation.

In particular, the researchers identified complex indels in the gene EGFR, which is implicated in lung cancer. If such an indel is found in this gene, Ding and her colleagues suggest a patient may benefit from an EFGR inhibitor, such as erlotinib, regardless of the tumor type. The investigators also found complex indels in a gene called KIT, which appears to play a role in melanoma. The analysis suggests that patients with complex indels in KIT would benefit from drugs such as imatinib, sunitnib and sorafenib, which target mutations in this gene.

The new software the investigators developed specifically to find complex indels is called Pindel-C. It was built on top of existing software called Pindel, which was published in 2009 by the study’s first author, Kai Ye, PhD, assistant professor of genetics. Both versions of the software are freely available online for download.