Three physician-scientists receive Doris Duke Charitable Foundation awards

Clinical Scientist Development Awards funds early-career scientists

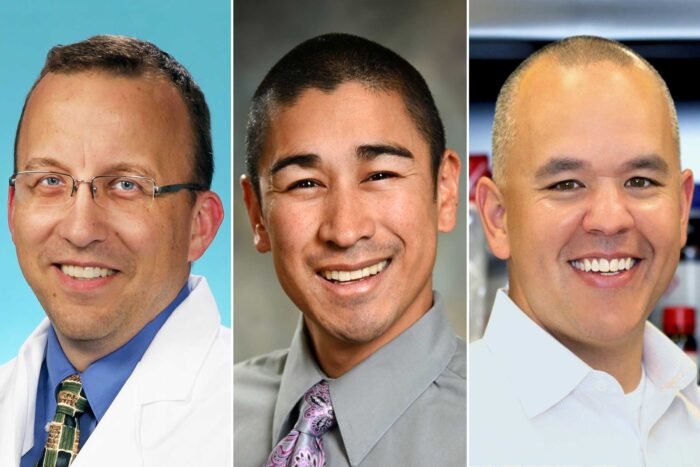

Three physician-scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a 2019 Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The award funds physician-scientists early in their careers. From left: Philip Budge, MD, PhD, Brian DeBosch, MD, PhD, and Andrew Kau, MD, PhD.

Three physician-scientists from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a 2019 Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Philip Budge, MD, PhD, Brian DeBosch, MD, PhD, and Andrew Kau, MD, PhD, are among 16 U.S. physician-scientists receiving the awards, which provide $495,000 over three years to each investigator.

The Clinical Scientist Development Award funds physician-scientists at the early stages of their careers. Faced with the competing demands of both caring for patients and conducting research, physician-scientists often experience a more challenging transition to an independent research career than other researchers. Through this award, early-career physician-scientists are able to protect and dedicate 75 percent of their professional time toward clinical research.

Budge, an assistant professor of medicine, studies lymphatic filariasis, a parasitic worm disease prevalent in tropical regions of Africa and Asia. His research addresses a key obstacle to eliminating lymphatic filariasis in Africa. In severe cases, lymphatic filariasis causes elephantiasis, painfully swollen limbs that make it difficult to walk and carry out daily activities. Programs to eliminate lymphatic filariasis depend on rapid diagnostic tests, but such tests are unreliable in 11 African countries where another worm parasite, Loa loa, is common. That’s because some people with L. loa infection – called loiasis – have antigens in their blood that cross-react with the rapid diagnostic tests for lymphatic filariasis.

Budge is working to determine which L. loa antigens cause cross-reactive tests, why such antigens are present in only a fraction of people with loiasis, and whether these cross-reactive antigens contribute to the adverse reactions that occur when some people with loiasis receive antiparasitic medications. The results of these studies will help researchers develop improved diagnostic tests for both lymphatic filariasis and loiasis that can help eliminate these neglected tropical diseases.

DeBosch, an assistant professor of pediatrics, studies nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a condition that affects roughly 25 percent of people in the U.S. and is closely linked to obesity. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction are effective therapies against the excessive accumulation of fat in the liver. DeBosch’s group discovered that blocking sugar from entering liver cells – the cells that regulate the body’s fasting responses – mimics many of the therapeutic effects of fasting. He is working to generate new therapies that block sugar transport into the liver cells in a “personalized” model of patient-derived liver-like cells. These personalized liver-like cells will be developed from patients’ urine and used to test novel drugs and genetic treatments. This modeling will be used as a bridge to identify which subsets of patients stand to benefit the most from each specific therapy.

Kau, an assistant professor of medicine, studies uropathogenic E. coli, the most common cause of urinary tract infections (UTI). They use a specialized adhesin protein called FimH to colonize the urinary tract as well as to establish reservoirs within the gut where they sometimes make their way to the urinary tract to seed infections. Kau will focus on understanding how a promising new investigational FimH-based vaccine, invented by Scott Hultgren, PhD, the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology, and subsequently licensed to and developed by Sequoia Sciences, works to prevent infection. His team hypothesizes that this vaccine may work both by preventing E. coli from sticking to the bladder and by selectively reducing uropathogenic E. coli within in the gut. Ultimately, targeting gut reservoirs of pathogens with vaccines like FimH could prove to be an effective approach to prevent drug-resistant infections.

“Physician-scientists are crucial to the clinical research field because they bring significant insights from their direct interactions with patients from the bedside to the bench,” said Betsy Myers, program director for medical research at the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. “For this reason, we are proud to support and protect the time devoted to research by these exceptional physician-scientists as they balance their clinical obligations with research work, ultimately giving them greater opportunities to make vital contributions to the field.”

Since 1998, the foundation has awarded more than $144 million in Clinical Scientist Development Awards. The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation works to improve the quality of people’s lives through grants supporting the performing arts, environmental conservation, child well-being and medical research, and through preservation of the cultural and environmental legacy of Doris Duke’s properties. The foundation’s Medical Research Program supports clinical research that advances the translation of biomedical discoveries into new preventions, diagnoses and treatments for human diseases.