Washington People: Audrey Odom John

Physician-scientist focused on developing new diagnostic tests, treatments to fight malaria

Robert Boston

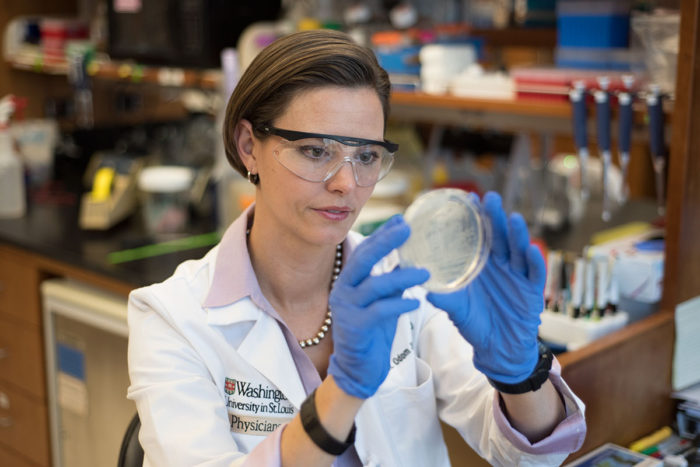

Robert BostonAudrey R. Odom John, MD, PhD, a globally recognized malaria expert at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, conducts research in the nine-member lab she runs in the Division of Infectious Diseases. The researchers hope to develop new diagnostic tests for malaria detection as well as antimalarial drugs.

Audrey R. Odom John is the mother to a boy, a girl and, over the years, hundreds of baby malaria parasites.

Scientifically named Plasmodium falciparum, malaria parasites in their infancy “need to be fed regularly, just like human babies,” said Odom John, MD, PhD, a highly regarded malaria researcher at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “But unlike people, baby malaria parasites like fresh blood. They’re little vampires. They can be high-maintenance.”

They also can be deadly. Transmitted by mosquitoes, malaria affects 214 million people worldwide — mostly younger children in sub-Saharan Africa — and causes 438,000 deaths annually, according to the World Health Organization.

“The good news is that malaria is preventable and curable,” said Odom John, 42, an associate professor of pediatrics and of molecular microbiology who has received dozens of awards and honors for her research on the devastating parasitic disease. “This is my focus.”

Her lab studies the chemicals produced by malaria parasites, with the goal of creating new diagnostic tools and treatments. For instance, Odom John and her colleagues are developing a device that would detect malaria with a simple, inexpensive breath test, similar to a Breathalyzer used to measure blood alcohol content.

Her quest to develop a breath test for malaria headlined a TEDx Talk in Kansas City, Mo., in late 2015.

“Audrey has distinguished herself as one of the School of Medicine’s finest young researchers,” said Gary A. Silverman, MD, PhD, the Harriet B. Spoehrer Professor and the head of the Department of Pediatrics. “Her expertise on malaria positions her at the global forefront in efforts to eradicate this disease.”

Odom John attended Duke University in her native North Carolina, earning a bachelor’s degree in biology (major) and chemistry (minor) in 1996 and, through the Medical Scientist Training Program at Duke, a doctorate in biochemistry in 2002 and a medical degree in 2003.

Following graduation, she went to the University of Washington in Seattle, where she completed her pediatric residency in 2005 and an infectious diseases fellowship in 2008.

What inspired you to focus on malaria?

I became interested in malaria foremost because it is an infectious disease that is extremely important to global health. It can be fatal, but it also can be prevented and treated. In addition, it’s a disease where basic science can directly lead to improvements in health. This is in contrast to diseases like measles, which is surprisingly common across the world, but where we already have an effective vaccine.

You oversee nine scientists in your lab, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Can you tell us about your research?

Our goal is to develop new diagnostic tests and antimalarial drugs. To do this, my lab studies malaria cultures in human red blood cells to understand the basic molecular and cellular biology of the parasite and the specific steps in metabolic pathways that lead to infection.

We’ve found that the malaria parasite produces chemical odors that attract mosquitoes. The parasite assembles such odors like molecular LEGOs, meaning one molecule gets added to another, and then another, to create chemical compounds called terpenes. The terpenes emit an odor that entices mosquitoes, which may explain why mosquitoes prefer to bite people infected with the malaria parasite.

These parasite-producing odors are the basis for the malaria breath test. Detecting the parasite in children’s breath may be inexpensive, quick and a lot less cumbersome and painful than current blood-based tests.

Imagine testing people at the border to make sure that malaria doesn’t come into the country with new travelers. Or testing and treating entire villages at a time. It’s hard to imagine doing either of those things with a blood test.

Can people or animals smell malaria?

We can’t really smell it, but the mass spectrometers we use can find it. There is not a definitive answer regarding animals; however, there is research interest in using dogs to detect the parasite.

What does the malaria parasite physically look like?

It is really beautiful. When it is stained under a microscope, the malaria parasite is a bright and distinctive pink and purple. Don’t get me wrong. The specimen itself is really horrible. That this one organism can cause such widespread mortality is awful. But looking at it is fascinating on all levels.

Courtesy of Audrey Odom John

Courtesy of Audrey Odom JohnCan you tell us about your family life?

I am married with two children, and we have two yappy dogs: Pip and Panda.

I’ve been married to my husband, Antony John, for 15 years. He is a music composer from England who also writes successful young adult novels, including the Elemental Trilogy. He also helps a great deal with our kids. He cooks. He chauffeurs. He literally makes my life possible.

We have two children: Gavin, who is 11, and Tamsin, who is 9. Gavin is into computers and coding, engineering and physics. Basically, anything related to math and science. The other day, he was reading “The Mathematics of Life.” It’s a thick, dense book. You know, a little light reading.

Tamsin likes to write books like her dad. However, she knows all about the malaria parasite. Both kids do. They would see me leave our house on weekends or hear me leaving in the middle of the night to feed baby malaria parasites. When Tamsin was 3, she grabbed my work bag, pulled it over her shoulder and announced, “I need to go feed my baby parasites.”

They also are familiar with malaria because they’ve watched Disney’s “The Winged Scourge.” They love it. It’s an animated short from the 1940s meant to educate people about mosquitoes spreading malaria. As a bonus, it features the Seven Dwarfs.

What was your childhood like?

I grew up in High Point, N.C. It’s a small town known for furniture factories. I have two older sisters and one younger brother. My parents are both certified public accountants, both still working. My dad is 82, my mom 72. Both went to a community college while working full time and earned associate degrees before sitting for the CPA exam. I’m the first to attend a four-year college and get a bachelor’s degree.

As I kid, I liked being outside on my dirt bike, building forts, running around. I’d get bruises or poison ivy, and none of it stopped me from playing outdoors.

I did well in school, and I loved science. I thought I wanted to go into marine biology, probably because I went to the beach and liked playing with crabs. I didn’t know about molecular biology until I enrolled in an academic enrichment program when I was 16. I remember listening to a lecture on recombinant DNA and my jaw hit the floor. I had no idea you could cut and paste DNA. I was in love. I still am. I’ve had the most fun with science ever since.”