Washington People: Bradley Schlaggar

Family's medical challenges deepen neurologist's understanding of what it means to be a doctor

Robert Boston

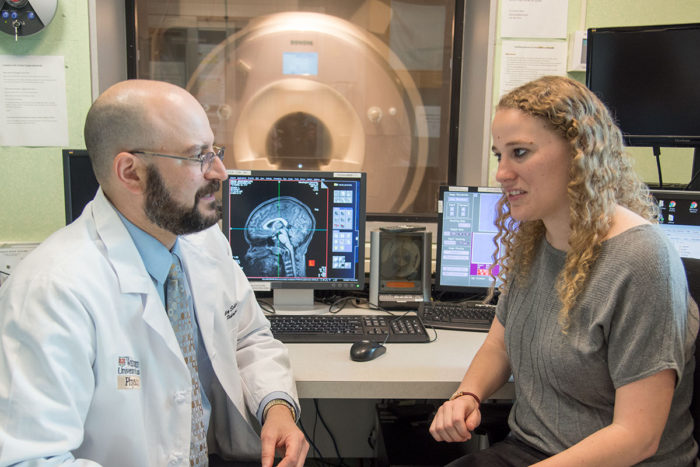

Robert BostonBradley Schlaggar, MD, PhD, discusses an MRI brain scan with graduate student Ashley Nielsen.

On a sunny day in late March, Bradley Schlaggar, MD, PhD, prepared to coach his son’s hockey team through its first practice of the season.

It would be the first time 11-year-old Simeon would be back on the ice since being declared in remission from leukemia.

“There’s a look you see in the eyes of parents of very sick kids,” said Schlaggar, who works as a pediatric neurologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis when not coaching hockey. “I understand that look in their eyes much more deeply now. There’s a lot of trauma that comes with seeing your child really, gravely ill.”

That empathy was hard-won. Simeon was diagnosed a year ago, sending the whole family into a months-long nightmare of chemotherapy and tests and endless days and nights in the hospital. Since December, though, Simeon has been on maintenance chemotherapy, and life is beginning to return to normal.

It was a tough time for a family that already has had more than its share of medical challenges. Schlaggar lost his sister to cancer in 1998, just shy of her 36th birthday. His father died in 2004, also from cancer. In 2012, he underwent urgent surgery and narrowly avoided a major heart attack at age 48. His wife, Christina Lessov-Schlaggar, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the School of Medicine, was diagnosed with breast cancer just two weeks later. She is now in remission.

“Each of these terrible experiences has taught me something about medicine and the medical system and what it means to be a doctor,” said Schlaggar, the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Neurology and director of the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology. “But nothing, nothing really comes close to what it’s like when it’s your own child.”

With Simeon back in school and the latest family health crisis easing, Schlaggar, who is also a professor of radiology, of psychiatry, of pediatrics and of neuroscience, has been able to turn his attention back to what he does best: studying how the brain develops, and how and why the patterns of normal development sometimes go awry.

“As a graduate student, the question I wanted to answer was, ‘Is a piece of cortex destined to serve a particular function, such as vision, or could it be cajoled to do something else?’” Schlaggar recalled.

Somewhat famously, he answered that question by slicing off a portion of a rat pup’s brain that normally would be destined to control vision, and relocating it into an area dedicated to the whiskers. The transplanted visual portion developed the characteristics of the whisker section.

“That was a cover-of-Science kind of experiment,” said Steven Petersen, PhD, who has collaborated with Schlaggar for nearly 20 years. Peterson is the James S. McDonnell Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience in the Department of Neurology. “Even today, after he has accomplished so much, he is probably still best known for that work. There was an ongoing debate at the time around how much plasticity the brain really had, and this experiment provided strong evidence that the cortex really isn’t set up in advance but maintains a fair amount of plasticity.”

After graduating from the Washington University Medical Scientist Training Program in 1994, Schlaggar completed a residency in child neurology at Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis Children’s Hospital in 1999 before joining the faculty of the School of Medicine that same year.

“The brain is what makes us human,” said Schlaggar, who is also neurologist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and co-director of the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Washington University. “In terms of the human experience, it’s all about what you perceive and communicate. The experiences you have – love, humor, inspiration – those are all mediated through the brain. To me, as a parent, as a child neurologist, optimizing every child’s cognitive outcomes seems like a valuable goal.”

Using MRI scans, he has shown that children’s brains are organized differently than adults’. From the outside, children and adults may look like they are doing the same thing – solving the same problem in the same amount of time – but under the hood, different parts of their brains are at work.

The networks of brain activity change as a child learns and grows. Schlaggar and colleagues are working on developing a “mental maturity scan” to reveal how a child’s brain changes along the path from childhood to maturity. Such a scan potentially could shed light on a range of psychological and developmental disorders.

“Dr. Schlaggar is a premier physician-scientist. He uses cutting-edge neuroimaging approaches to study human brain function and its development both normally and in the context of developmental diseases, all the while leading one of the top pediatric neurology programs in the world,” said David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor of Neurology and head of the Department of Neurology. “On top of all that, he’s a great person to work with whether you are a student, resident, fellow, faculty member, staff member or administrator.”

Schlaggar’s interest in neurology dates back to high school, when he received a special edition of Scientific American in the mail. The edition was devoted to the brain.

“It came out in 1979, and I still have it,” Schlaggar said. “The articles were right at the cutting edge of ideas about how the brain works and the nervous system develops, and I was just taken by the whole idea that the brain was organized so that different parts of the brain carry out different cognitive functions. I thought it was just the coolest thing.”

Schlaggar also studies how the brain learns to read, an interest he picked up as a child from his mother, a pioneer in gifted education in the Chicago public schools.

“As a kid, our dinner-table conversations consisted of my mom talking about teaching children to read and my dad talking about the futility of the Cubs,” Schlaggar said.

Today, Schlaggar is on the board of Ready Readers, a local nonprofit dedicated to inspiring a love of reading in preschoolers from low-income communities. It dovetails with his research and also fits with what he calls his “hippie values,” which involve contributing to the local community and supporting social justice.

“The premise of Ready Readers is that if we could invigorate a reading culture, it would be an effective way of improving the reading readiness of those kids,” Schlaggar said. “It’s not going to solve all the issues associated with growing up in low socioeconomic-status environments, but it’s a great idea.”

Before joining Ready Readers, Schlaggar served for six years on the board of Friends of St. Louis Public Radio. Three years ago, he turned his 50th birthday celebration into a fundraiser, throwing a party that drew about 150 people and earned over $8,000 for the station.

He does this because, after 31 years in St. Louis, Schlaggar now sees it as home.

“I didn’t expect when I arrived in 1986 to become a lifer,” Schlaggar said. “But I don’t think you can find another place that is so enjoyable to live and work in, and I’ve looked. The school and hospital system are excellent, and the community is amazing. With the recent life events in my family, the community just rose up to support and embrace us.”

For many years, he regularly played basketball with friend and colleague Andrew J. White, MD, the James P. Keating Professor of Pediatrics and vice chair of medical education in the Department of Pediatrics.

“I’m delighted that he, too, has finally gone bald,” quipped White, who trained as a resident physician alongside Schlaggar. “The days of his mullet whipping around the court, fouling and entangling his opponents, are happily now just distant memories.”

These days, Schlaggar and his wife and kids, Simeon and 9-year-old Lena, are more interested in baseball and hockey than basketball.

Courtesy of Schlaggar Family

Courtesy of Schlaggar Family“When the kids first came along, Christina and I discussed carefully how we were going to raise them, because we come from very different backgrounds, you know. So we thought about it a long time – it’s a very important question – and in the end we decided not to raise the kids as Cubs fans. We just couldn’t do that to them,” said Schlaggar. For a few moments, he laughs uproariously at his own joke, and then continues, more seriously.

“It’s hard to remember what life was like before cancer. We are big Cardinals and Blues fans, but we’ve just started going to sporting events again,” he said. “It’s nice to be out coaching again. It’s my son’s first time back on the team, joining some old friends he’s played with before, and I’ll get to be on the bench with him. It’s a benchmark, for life is getting back to normal.”