Washington People: William Hawkins

Losses due to cancer inspired physician’s pursuit of medicine, research

Robert Boston

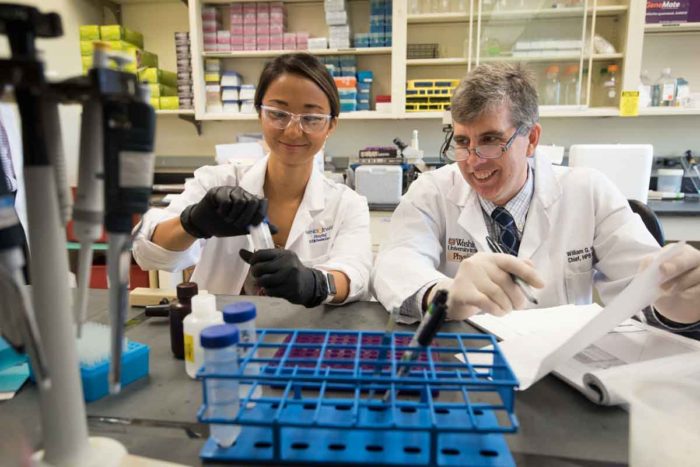

Robert BostonLinda Jin, MD, a Washington University School of Medicine research fellow, and William Hawkins, MD, a professor of surgery, work in Hawkins' lab. Principal investigator of a $10.4 million federal grant, Hawkins leads a national group of scientists working to develop new treatments for pancreatic cancer.

William Hawkins, MD, never met the man who helped inspire him to become a cancer surgeon and researcher. Hawkins was born six months after his grandfather Gabriel Jooris, an artist and art restorer, died of the disease. But the family stories Hawkins heard painted a picture of someone who was larger than life.

Jooris grew up in Belgium during World War II, when the Nazis stole and destroyed many works of art. He would go on to write a book, translated into dozens of languages, about restoring art instead of painting over it – a common practice at the time.

“After he came to the United States, he would wrap a Monet or another famous painting in brown paper, get on the subway, bring it back to his Queens apartment – this million-dollar painting – and restore or clean it for The Metropolitan Museum of Art or Museum of Modern Art,” said Hawkins, whose middle name is Gabriel, in honor of his grandfather.

“He apparently was the life of a party. He participated in church plays. He was a professional artist; he did stained glass and needlework. He has work in museums in Canada. That somebody who was so meaningful to my family had cancer really affected me.”

As a child, Hawkins lost a cousin and a classmate to cancer, too.

“While I didn’t know then that I wanted to be a doctor, I thought I wanted to do something about the problem of cancer,” he said.

Today, Hawkins is the Neidorff Family and Robert C. Packman Professor of Surgery and chief of the Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic and Gastrointestinal Surgery Section at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a physician at Siteman Cancer Center.

He recently was named principal investigator of a prestigious $10.4 million, five-year Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) grant, funded by the National Cancer Institute. As such, he leads a national group of researchers tackling pancreatic cancer. One of the deadliest cancers, it has a one-year survival rate of 27 percent and a five-year survival rate of about 8 percent.

“We need to do something brave, something innovative, something big,” Hawkins said. “Incremental is not working with this disease.”

Robert Boston

Robert BostonYou’re working with a variety of experts: basic scientists, medical oncologists, surgeons. What is most appealing about this approach?

We have a brutally honest team of about 35 researchers. These are independent thinkers; they’re strong-willed people. They know this disease, and they are looking to do something different. We also have an advisory board that includes patient advocates. I think it’s the integrity, the honesty, the diversity of experience and the shared purpose. A team might have a geneticist, a chemist, a biologist and a patient who wants a treatment to do more than kill cancer only in mice. They want to know what it will do for people. We get in some heated discussions, but we also get some really good science.

Any downsides?

If there’s a challenge with this group of investigators – they are so smart – it’s if you find something that’s really interesting but isn’t going to help us, we don’t have time to explore it.

Does the low survival rate of pancreatic cancer create a greater sense of urgency?

I also treat patients with pancreatic cancer, and there’s hardly a week that goes by that I don’t lose somebody to this cancer. Several of the other researchers also are clinicians. We have several patients on the grant advisory board. So it is not hard for us to remember that purpose. It’s in our face with this disease.

How does a surgeon get involved in such seemingly different pursuits as immunotherapy and drug development, which are part of the grant?

If I were solely a surgeon, knowing the one-year survival rate of pancreatic cancer patients is only 27 percent, that would be a depressing job. I signed up for academic medicine, being at a research center, because I wanted to tackle a problem. I wanted to leave a mark. So every additional year my patients get – every additional birthday, every graduation, every grandchild they see – is a mark. There’s also this part of you that wants to do something that’s bigger than your individual impact on patients. So while my clinical life is very busy and gratifying, research is my hobby. It’s going some place nobody has ever gone before.

Do the roles of clinician and researcher require different mindsets?

When a young surgical resident comes to us to do research, this person has been successful at 95 percent of everything he or she has done. But when you take on research, which involves a lot of trial and error, and you’re asking bold, novel questions, you go to a 90 percent failure rate. You almost have to be a different person when you’re in the lab than when you’re in the clinic.

Still, there’s enjoyment in both roles. It’s like when you’re on a hike, walking through the woods, you can appreciate the pine needles and trees, but you can’t see anything. Then, you crest the hill and look on the horizon and see where you’ve come from and where you’re going.

You mention hiking. Is that a hobby?

Courtesy of W. Hawkins

Courtesy of W. HawkinsI am of the work-hard, play-hard philosophy, and I’m also a family guy. My sons, Will and Patrick, are Boy Scouts, so I backpack with them. Last year, we did 10 days in the woods with no cell phone. That was cool. I also run the WashU ski club. I guess I have a bit of an adventurous spirit.

There are times to be cautious, and there are times to be a risk-taker. With the grant, with the basic sciences, it’s time to be a risk-taker. When you’re caring for the individual patient, you’ve got to do the best thing for that patient.

What about each role energizes you?

I recently saw a young woman we had cured of a bad cancer. I saw her on her fifth-year anniversary of being cancer-free. She brought me a little bag of chocolate and a thank-you card with a picture of her and her 6-year-old son. It doesn’t get any better than that. The other thing that energizes me is when you do an experiment and find something new that no one else in the world knows about. It is like you are 5 years old and you have a secret you can’t wait to tell.

None of this would be possible without the generous, brave individuals from our community who have participated in our research. And I thank them.