White Coat Ceremony marks beginning of medical training

124 students receive white coats, recite class oath

Matt Miller

Matt MillerArmando Arroyo Mejías receives his white coat from Lisa M. Moscoso, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics at WashU Medicine. Arroyo Mejias was among 124 new students at WashU Medicine to receive their white coats in a ceremony at Graham Chapel Friday, Oct. 18.

Few items of clothing are as tied to a profession as a white coat is to being a doctor. For patients and their families awaiting news of a test result, a diagnosis or a treatment plan, the coat signals expertise, responsibility and even hope. Donning white coats for the first time Friday, Oct. 18, members of the newest class at Washington University School of Medicine felt the full weight of that cotton-polyester coat.

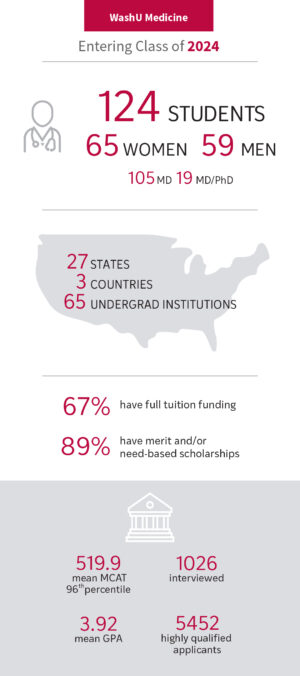

Friends and family of the 124 new medical students filled Graham Chapel on the Danforth Campus to witness them receive their white coats from faculty members involved in their training. They then recited their class oath, which they had crafted as a team.

“It is a powerful symbol of the medical profession’s profound responsibility, unwavering dedication and deep commitment to healing,” said Tammy L. Sonn, MD, associate dean for student affairs and a professor of obstetrics & gynecology, in her welcoming remarks.

This year’s cohort includes members of Gen Z fresh from their undergraduate degrees, to early-vintage Millennials arriving from other careers. The class has 65 women and 59 men. Slightly over a quarter are from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, and 89% have received a merit- or needs-based scholarship. They were drawn to St. Louis from more than half of the states in the U.S., as well as from Canada and France.

In his address at the ceremony, David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, the George and Carol Bauer Dean of WashU Medicine, and the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor, said that strangers gathering together to pursue the welfare of other people, as these students had chosen to do, is the heart of medicine.

“This ability to care about a person you don’t even know is the miracle of human civilization,” Perlmutter said. “Human bodies fail and they suffer and they hurt each other, and we are the ones charged with fixing them, comforting them and figuring out ways to get them back on their feet.”

That theme of service was echoed by the keynote speaker, Dineo Khabele MD, the Mitchell & Elaine Yanow Professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, who recalled her early training in New York at the height of both the AIDS and crack cocaine epidemics. Those patient populations were not always treated with the full dignity they deserved from the medical profession, she said.

“The white coat on its own is not enough; you have to earn the trust of the patients that you serve,” she said. “That trustworthiness comes from your credibility, your competence and your compassion.”

Lauren Everett, president of the new class, served as a medic in the U.S. Air Force for several years, during which she was deployed to Afghanistan. On being promoted to a more supervisory role, she realized that emergency medicine was calling her back.

“You have this opportunity to be the calm in someone else’s storm, and I find that very fulfilling,” Everett said. Nevertheless, she added, becoming a doctor “is a little bit intimidating. We’re going to be the ones who people are going to come looking for when things go wrong, so there’s a level of increased responsibility.”

As a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at WashU, Larissa Rays Wahba is drawn to the lab and the clinic. A native of Brazil, Rays Wahba moved to New York while in middle school. Shortly after, her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. The family needed to navigate the medical system of a new country in a foreign language.

“There was definitely a lot of fear and confusion,” Rays Wahba said. “But if it hadn’t been for the patience and communications of my mother’s care team to our family, I don’t think she would have had such a successful outcome.”

Rays Wahba’s desire to conduct research was inspired by her mother, who despite the demands of pursuing a law career and raising two daughters, decided to participate in post-treatment medical studies. This introduction to the research component of medical practice is a big part of Rays Wahba’s motivation to study at WashU Medicine. The White Coat Ceremony is a recommitment to those twin desires for service and expanding knowledge.

“Putting it on means that you now have a responsibility to yourself, to your patients, to your community and to society as a whole,” Rays Wahba said.