Young people with disabilities focus of COVID-19 testing grant

$5 million grant to fund saliva tests for students, teachers, staff in schools operated by Special School District of St. Louis County

Matt Miller

Matt MillerResearchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a grant allowing them to offer 50,000 saliva tests for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to students, teachers and staff in the six special education schools operated by the Special School District of St. Louis County.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a two-year, $5 million grant to offer 50,000 saliva tests for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to students, teachers and staff in the six special education schools operated by the Special School District of St. Louis County (SSD).

The pandemic has disproportionately impacted students with special needs, especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities, in part because they rely on daily structure and in-person support for learning and social growth. The researchers also will assess educational disparities affecting families whose children have intellectual, emotional and developmental disabilities. Due to underlying medical conditions experienced by many such students, this population of students is at a higher risk for developing COVID-19 and severe complications of the virus.

The grant will serve about 750 families in the district who have children in kindergarten through the 12th grade. The saliva tests will be voluntary and offered weekly to teachers, staff and students over the next year, starting this fall.

“Our partnership with the Special School District strives to remove the obstacles related to testing and decrease the burden of COVID-19 for this vulnerable segment of the population,” said grant co-investigator Christina A. Gurnett, MD, PhD, the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Developmental Neurology and director of the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology.

The funding stems from $500 million awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to 32 medical centers as part of the agency’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics-Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) initiative to provide underserved communities with rapid testing for COVID-19. This award supplements the Washington University Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC), which aims to advance research in neurodevelopmental disorders and is funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

“Remote school is difficult for most families, but particularly so for parents who have children with disabilities,” said Gurnett, who serves as neurologist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “Parents, especially if they’re working and if they have other children, may not be able to provide full-time caregiving. Their children may have trouble interacting with computer screens, and their behavior may be negatively affected by feelings of confusion and isolation. Children with disabilities may also require ongoing assistance with basic skills such as eating or using the bathroom.”

Such caregiving duties also put teachers at an increased risk of exposure to the coronavirus and present additional hurdles if families and teachers need to quarantine for two weeks.

“The widespread closure of schools has significantly impacted the well-being of children in general and this population in particular,” said Jason Newland, MD, co-principal investigator of the grant and a professor of pediatrics in the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. He has advised multiple school districts in Missouri on plans for reopening schools.

“It is a major priority to get children with disabilities back into the schools while providing a safe environment for the students and staff,” said Newland, who treats patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “A key component of achieving this goal in this vulnerable population is ample testing that can rapidly detect COVID-19 infections within the school community.”

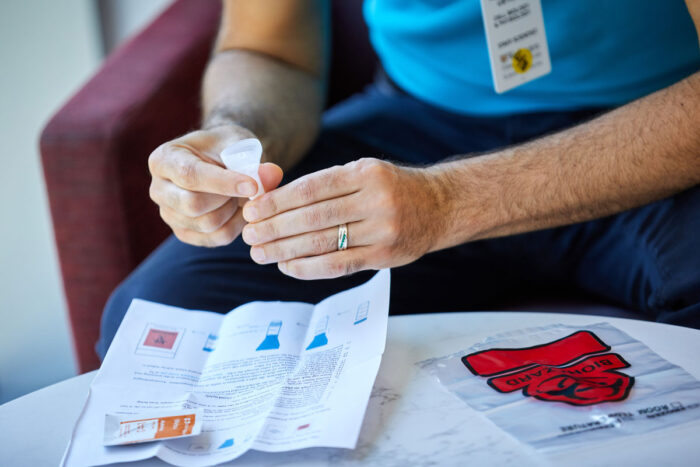

The saliva test provides easy and fast testing with same-day results, ideal for screening large communities. It was developed by the School of Medicine’s Department of Genetics and the McDonnell Genome Institute, in collaboration with a biotechnology company.

“The Special School District is eager to partner with Washington University to improve the lives of students with disabilities, especially during this time of COVID,” said Elizabeth Keenan, PhD, SSD’s superintendent.

SSD’s special education schools serve students from all school districts in St. Louis County, including those residing in socioeconomically stressed neighborhoods, where many families have heightened exposure to COVID-19, as well as disproportionate vulnerability to its most serious consequences. SSD’s students returned part time to in-person learning in November.

The project will be shaped by ongoing advice from a community advisory board made up of diverse members of the public and convened by the Institute for Public Health, the Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences and the IDDRC. The grant also involves faculty members from the Brown School and investigators at the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s Institute for Human Development, and Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore to survey national attitudes about the impact of COVID-19 on the health, wellness and education of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

John N. Constantino, MD, the Blanche F. Ittleson Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics and psychiatrist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, is a co-principal investigator. He and Gurnett co-direct the IDDRC, which is one of 15 research centers funded by the NICHD to advance understanding of conditions related to intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Among noninfected people in the United States, “few are more adversely affected by COVID-19 than individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, given that a vast proportion require in-person care or critical therapeutic support within their living environments, with little backup or systematic coverage for prolonged interruption of services,” wrote Constantino in a letter published Aug. 28 in The American Journal of Psychiatry, on behalf of the directors of the nation’s 15 Eunice Kennedy Shriver IDDRCs. “Many have temporarily lost access to trained caregivers or community service providers and now face evolving threats to the return of baseline service, given uncertainties in state and agency budgets. Therefore, a first priority relates to restoration of in-person support services or comparable alternatives.”