Americans trust their doctors, but doubt the system

New center to develop AI-based imaging tools to improve diagnosis, care

Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis is establishing a new center dedicated to developing AI-based imaging tools to improve the diagnosis and precision treatment of cancers, cardiovascular disease, neurological diseases and numerous other conditions. The new Center for Computational and AI-enabled Imaging Sciences brings together collaborators from across WashU Medicine and others from WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering.

AI already has shown promise for its ability to analyze vast collections of medical images to generate clinically relevant insights, identifying patterns and anomalies that physicians might otherwise not detect on their own.

“Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology has long been a national leader in developing innovative imaging technologies, from the invention of positron emission tomography to today’s AI applications in diagnostics and image analysis, and this new center represents an ambitious expansion of our capability,” said Pamela K. Woodard, MD, the Elizabeth E. Mallinckrodt Professor and head of MIR at WashU Medicine. “Integrating AI into imaging will enhance how we diagnose disease, predict its progression and tailor treatments to the unique needs of each patient.”

The new center will help advance AI-driven imaging technologies, such as two recently developed at WashU Medicine — in collaboration with MIR — that are being commercialized. One tool can analyze mammograms to predict an individual patient’s risk of breast cancer over the next five years. Another rapidly maps the brain to help neurosurgeons plan delicate surgeries and avoid sensitive areas that control speech, movement and cognitive function. The center will be a hub for expertise in image analysis that uses sophisticated computing tools to find patterns in datasets of millions of medical images and de-identified patient records, providing insight on both the progression and the potential treatment of disease. The center will also support training on these tools for clinicians and researchers.

The new center will join a growing WashU ecosystem of collaborative AI initiatives that are helping to shape the future of medicine. These include the Center for Health AI (CHAI), which was established as part of the joint agreement to build deeper collaboration between BJC Health System and WashU Medicine and is focused on making health care more personalized and effective for patients and more efficient for providers; and the AI for Health Institute at WashU McKelvey Engineering, which is working on other AI-powered medical innovations.

The Center for Computational and AI-enabled Imaging Sciences will primarily focus on developing AI-based medical imaging applications that integrate information from different imaging types — ranging from digital microscope images of cells to MRI scans to X-rays — to identify clinically informative connections between them. This may include identifying previously unknown early indicators of disease onset that could allow for more effective clinical interventions.

The center will bring together AI imaging experts and researchers from across the Medical Campus, including Siteman Cancer Center, based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and WashU Medicine, and from the school’s Departments of Medicine, of Neurology, of Psychiatry and of Radiation Oncology.

A clear image of the future of medicine

The new center will house information from the imaging databases of all the participating departments, collectively representing a range of imaging modalities across many different types of disease. The AI-powered tools developed from those large datasets will enable increasingly precise diagnosis for individual patients, Woodard said.

AI algorithms applied to medical imaging have already been used to detect and classify new subtypes of some disorders in ways that can guide clinical treatment decisions. The breadth of information that will be available at the new center will accelerate this work in a broader range of conditions.

The new center will be led by Mark Anastasio, PhD, a leading expert in computational imaging science and AI for imaging applications. He joins WashU as the Mallinckrodt Endowed Professor of Imaging Sciences for MIR, where he will also be the Vice Chair for Imaging Sciences and AI Research. He will also be Professor of Electrical & Systems Engineering in McKelvey Engineering. Anastasio comes to WashU from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he has served as head of the Department of Bioengineering for the past six years.

“Institutions with leading academic medical centers that unite medical data, clinical expertise and advanced AI research will lead the next revolution in healthcare,” said Anastasio. “WashU is exactly such an institution and an ideal home for this center that will enable us to build a community to drive innovation that advances patient care in ways few other institutions can achieve.”

As part of that community building, Anastasio will join the leadership team of the Oncologic Imaging Program at Siteman Cancer Center. He will also be the associate Chief Research Information Officer for Biomedical Imaging at the Institute for Informatics, Data Science & Biostatistics (I2DB), where he will work with institute director Philip R.O. Payne, PhD, the Janet and Bernard Becker Professor of Medicine. Payne is also the chief health AI officer for CHAI and the Vice Chancellor for Biomedical Informatics and Data Science at WashU Medicine.

“AI-enabled imaging has the potential to be as transformative for medicine as earlier waves of innovation — from the adoption of electronic health records to the rise of precision medicine and the advent of real-world evidence generation,” said Payne. “That transformation is being realized here at WashU Medicine because of the dynamic and collaborative environment that exists at our institution, exemplified by leading-edge, transdisciplinary initiatives like this one.”

Aaron Bobick, PhD, dean of WashU McKelvey Engineering and the James M. McKelvey Professor, said dedicated centers such as this will be crucial to maximizing the medical and engineering expertise needed to build out the potential for AI in medical applications.

“Medical imaging offers some of the most exciting challenges in imaging science and artificial intelligence, both of which are core domains for McKelvey Engineering,” said Bobick. “I am certain that the innovations that this center will facilitate by combining the skills of WashU Engineering faculty with the broad range of medical expertise at WashU Medicine will lead to advances that both drive the science forward and benefit patients.”

Discovery of viral entry routes into cells points to future prevention, treatment strategies

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified central routes that two deadly viruses take to invade human cells and have designed decoy molecules that block the infections.

The discoveries — published this week in two separate studies — set the stage for developing new prevention and treatment strategies for yellow fever virus and tick-borne encephalitis viruses, members of a group of viruses that includes Zika, dengue, West Nile and Japanese encephalitis viruses. With shifting climate conditions, such viruses are expanding their ranges, increasing the threats they pose to public health.

The study on yellow fever virus appears in Nature, and the study focused on tick-borne encephalitis viruses is published in PNAS.

“There are no treatments for these viral infections, so there is an urgent need for new strategies to prevent and treat these infections, which continue to cause severe disease and death in far too many cases,” said Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, senior author of both studies and the WashU Medicine Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine. “Our studies showing how these viruses get into cells creates opportunities to disrupt those routes, stopping viral infections from jumping animal species — both wild and domesticated — and spreading through populations of people.”

Yellow fever virus is spread by mosquitoes and is common in parts of Africa and South America. Many people infected experience flu-like symptoms and recover. According to the World Health Organization, about 15% of infections are severe, causing high fever, liver failure, internal bleeding and toxic shock. About half of cases that come to clinical attention — which number in the tens of thousands each year — end in multi-organ failure and death. Vaccination can protect against yellow fever, but the sole vaccine available uses a live virus, so people with weakened immune systems, including infants and older adults, cannot take it.

Tick-borne encephalitis virus is spread by several tick species, and different versions of the disease occur across parts of Europe, Russia and Northern and Eastern Asia. Severe forms of the infection cause inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, leading to neurological disease and death. An inactivated vaccine exists for only one subtype of this virus and is most often recommended for travelers at high risk of exposure to ticks in endemic areas.

Decoys serve as viral distraction to block infection

Over a century of studying these viruses, scientists had not understood how they infect cells. Knowing the infection route is a crucial step to impeding viral entry.

“Vaccine development for both of these viruses first started in the 1930s; in the case of yellow fever, we are still using the same live-attenuated vaccine developed in 1937 by Max Theiler, who later won a Nobel Prize for the discovery,” said co-author Daved Fremont, PhD, a professor of pathology and immunology, of biochemistry and molecular biophysics, and of molecular microbiology at WashU Medicine. “Our new studies are a step toward the development of a new generation of vaccines and antiviral strategies for active infections. This work exemplifies the remarkable expertise that the WashU Medicine community can bring to bear on a significant biomedical issue.”

The researchers used genetic techniques, including CRISPR gene editing technology, to identify a family of cell-surface proteins called low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLR) as the main route these viruses use to enter cells. The researchers focused on these particular receptors because of their own and others’ past work identifying them as important entry receptors for other types of viruses, including alphaviruses such as Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

In Nature, the researchers are the first to report that yellow fever virus latches onto LDLR receptors LRP1, LRP4 and VLDLR.

In PNAS, they showed that tick-borne encephalitis viruses enter cells via a different family member, LRP8 — a finding similar to that from a recent study by another group that implicates the same receptor.

The researchers found that genetically eliminating these receptor proteins from the surfaces of cells blocked the viruses from infecting those cells. They also found that adding abnormally high numbers of these receptors to cells allowed more virus to enter.

The specific receptors they identified may explain why the viruses have different impacts on different organs in the body. For example, high amounts of LRP1 are found on the surface of liver cells, and yellow fever virus infection can cause severe liver disease. Likewise, LRP8 is found primarily on the surface of cells in the nervous system, helping explain the severe neurological symptoms characteristic of tick-borne encephalitis virus.

In both studies, the team designed “decoy” molecules that include a piece of an antibody attached to the entry receptors, which are not embedded in cells — a strategy that tricks the viruses into latching on to the decoys rather than the cells, thereby protecting cells from infection. The decoy molecules prevented infection in human and mouse cells in the lab. They also protected immunodeficient mice from what is typically a lethal dose of yellow fever virus, compared with mice receiving a placebo decoy. The receptor decoys also prevented liver cell damage in mice engrafted with human liver cells.

According to the researchers, this antiviral strategy is appealing because the decoy is based on a human protein that won’t evolve, rather than a viral protein that will always be a moving target, adapting to evade therapies targeted against it. In theory, if the virus mutates to evade the decoy, it is also adapting away from its ability to bind the human protein, making it less infectious, according to Diamond, also a professor of molecular microbiology and of pathology and immunology.

TIME Magazine names therapeutic microbiome-directed food a Best Invention of 2025

An innovative therapeutic food designed to treat childhood malnutrition has been named one of TIME Magazine’s Best Inventions of 2025.

The team behind the therapeutic food is led by Jeffrey I. Gordon, MD, the WashU Medicine Dr. Robert J. Glaser Distinguished University Professor, and his collaborator Tahmeed Ahmed, MBBS, PhD, at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b).

This therapeutic food, called microbiome-directed complementary food-2 (MDCF-2), is specifically designed to repair the abnormally forming gut microbiomes of children suffering from malnutrition. Clinical trials in Bangladesh have established that the food boosts the activities of gut microbes that play key roles in many facets of growth and development, including effects on proteins involved in regulating musculoskeletal development, brain development, metabolism and immune function. The benefits produced by MDCF-2 are far greater than those produced by a commonly used therapeutic food that was not designed to repair the microbiome.

Gordon’s team has identified the active compounds in MDCF-2 recognized by gut microbes and how these molecules are transformed, yielding new and deeper understanding of how food is connected to health through the activities of the gut microbiome. The work of the WashU-icddr,b team with MDCF-2 is providing a new perspective on the underpinnings of healthy growth — a perspective that emphasizes the necessity of having a properly choreographed program of co-development of the microbiome and the various organ systems of infants and children.

Clinical trials of the microbiome-directed food, involving nearly 7,000 children of different ages and degrees of malnutrition, are currently underway across sites in South Asia and Africa. The trials are funded by the Gates Foundation and conducted in collaboration with the World Health Organization.

WashU Medicine elevates Aagaard, Zehnder to expanded education leadership roles

Two top deans in the WashU Medicine Office of Education have been promoted to take on more expansive roles leading the education and training of the next generation of health and science professionals during a time of rapid change and emerging technologies.

Eva Aagaard, MD, the Carol B. and Jerome T. Loeb Professor of Medical Education, has been named the school’s vice dean for education and will continue her university role as vice chancellor for medical education. She has been the senior associate dean for education since 2017.

Nichole Zehnder, MD, the associate dean for educational strategy, will become the senior associate dean for undergraduate medical education.

Their promotions take effect Nov. 1.

“WashU Medicine has been a world leader in medical education, home to the most talented students, and we have been fortunate to recruit the best possible leaders for this important part of our mission,” said David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor and the George and Carol Bauer Dean of WashU Medicine. “Drs. Aagaard and Zehnder have utilized the scientific principles of education to modernize our curriculum and provide state-of-the-art coaching and mentoring to advance the learning experience. Remarkably, they’ve accomplished this amidst enormous challenges from the changing world around us.”

A national leader in medical education, Aagaard spearheaded the medical school’s highly regarded Gateway Curriculum, which launched in 2020 at the height of the pandemic. In addition to the MD program, she also oversees all the school’s offerings in graduate medical education, including 199 esteemed residency and fellowship programs, allied health professions programs and WashU Medicine’s PhD programs in the Roy and Diana Vagelos Division of Biology & Biomedical Sciences (DBBS). Regarding the latter, Aagaard is supporting a renewal of the curriculum and organizational structure led by DBBS director Steven Mennerick, PhD, associate dean for graduate education and the John P. Feighner Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Aagaard’s efforts have extended beyond students and trainees through multiple initiatives promoting faculty success. Among them is the Academy of Educators, which offers programs, workshops, grants and awards that support professional growth.

“Dr. Aagaard is a true visionary whose impact on the students, faculty and staff at the medical school, and across the university, has been life-changing in the most positive way,” Perlmutter said. “Her courage and creativity have been essential in catalyzing the changes that were necessary to continue the legacy of WashU as a powerhouse in medical and scientific education and training.”

While Aagaard will continue to support graduate and undergraduate medical education, her new title recognizes her broader responsibilities across the university and Medical Campus.

“We’re in a time of significant change in graduate and professional education,” Aagaard said. “My new role allows me to proactively assess risks and provide support and resources to ensure the ongoing success of all our excellent programs.”

Aagaard joined WashU Medicine in 2017 after serving as a professor of medicine and associate dean for educational strategy at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and as director of the University of Colorado’s Academy of Medical Educators and its Center for Advancing Professional Excellence.

As associate dean for educational strategy, Zehnder has overseen multiple learner and faculty success programs, partnerships with WashU Disability Resources, dual-degree programs and EXPLORE, an immersive and longitudinal program created as part of the Gateway Curriculum. EXPLORE aims to help aspiring doctors find their niche in academic medicine.

Zehnder also led the launch of the new curriculum’s coaching program, which many students have cited as one of their favorite parts of their education. The program involves faculty coaches — trained by Zehnder in topics such as navigating difficult conversations — who meet with students in small groups and individually throughout their time at WashU Medicine. Coaching sessions encourage students to share thoughts about communal experiences encountered in medical school and medicine in general. Students also talk about academic and personal victories and struggles.

“Along with her medical expertise and teaching talents, Dr. Zehnder has an incredible gift for connecting with both the students and the faculty,” Perlmutter said.

In her new role, Zehnder will assume greater oversight of medical student education, including supporting the integration of artificial intelligence into the curriculum, advancing student success and ensuring admissions continue to align with WashU Medicine’s core mission of education, patient care and research.

Zehnder joined WashU Medicine in 2020 after serving as the assistant dean of admissions, assistant dean of student affairs and clerkship and sub-internship director in internal medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

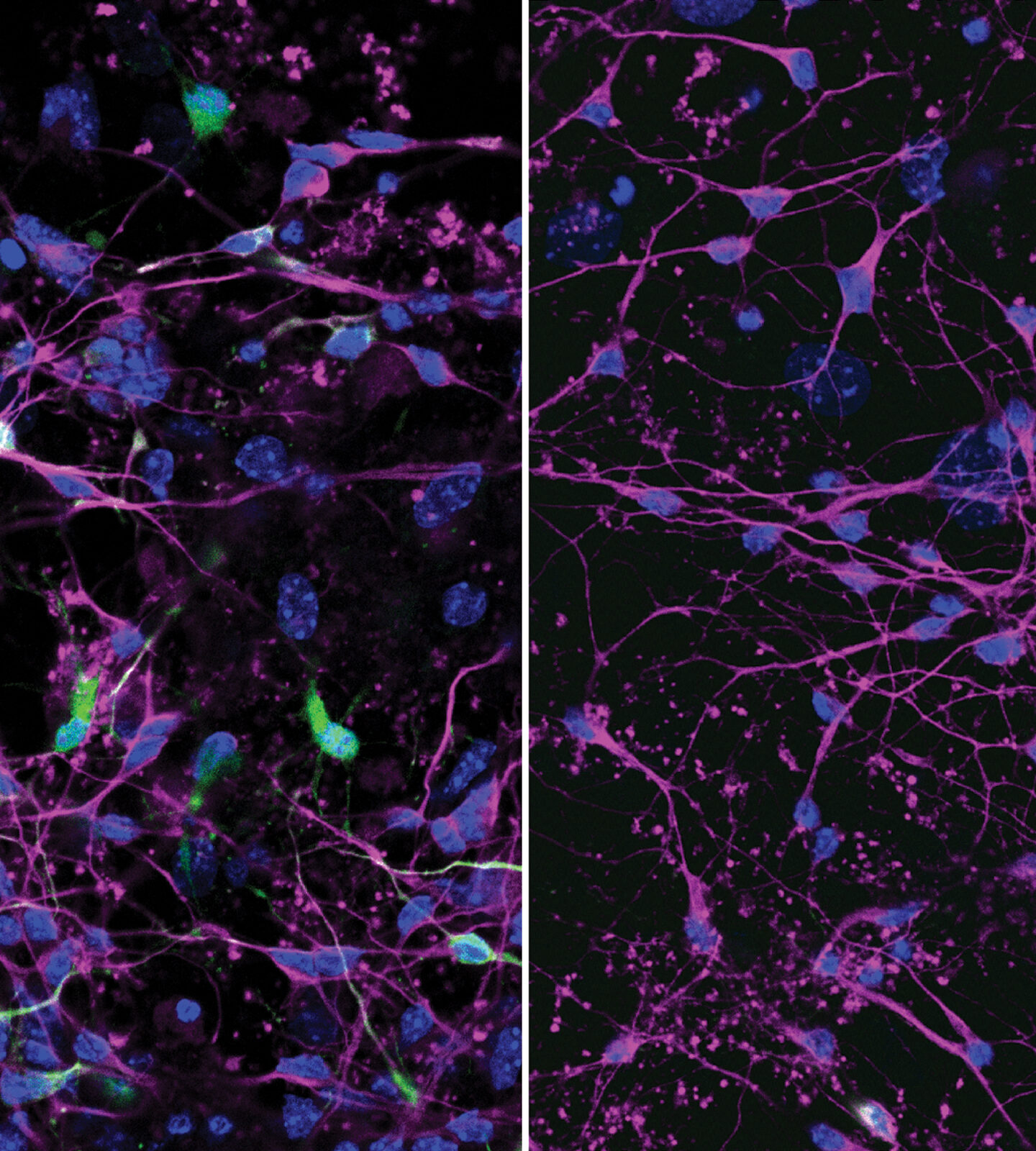

Alzheimer’s disrupts circadian rhythms of plaque-clearing brain cells

Alzheimer’s disease is notorious for scrambling patients’ daily rhythms. Restless nights with little sleep and increased napping during the day are early indicators of disease onset, while sundowning, or confusion later in the day, is typical for later stages of the disease. These symptoms suggest a link between the progression of the disease and the circadian system — the body’s internal clock that controls our sleep and wake cycle — but scientists did not know the full nature of the connection.

Researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have now shown in mice that the circadian rhythms within particular brain cells are disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease in ways that change how and when hundreds of genes regulate key functions in the brain.

The findings, published October 23 in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that controlling or correcting these circadian rhythms could be a potential way to treat the disease.

“There are 82 genes that have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and we found that the circadian rhythm is controlling the activity of about half of those,” said Erik S. Musiek, MD, PhD, the Charlotte & Paul Hagemann Professor of Neurology at WashU Medicine, who led the study. In mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease, the typical daily activity patterns of those genes were altered. “Knowing that a lot of these Alzheimer’s genes are being regulated by the circadian rhythm gives us the opportunity to find ways to identify therapeutic treatments to manipulate them and prevent the progression of the disease.”

Musiek, the co-director of the Center on Biological Rhythms and Sleep (COBRAS) at WashU Medicine and a neurologist who specializes in aging and dementia, said that changes in sleep patterns are among the most frequent concerns reported to him by caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. He and colleagues have previously shown that these changes begin in Alzheimer’s years before memory loss becomes apparent. He noted that in addition to creating burdens for caregivers and patients, disrupted sleep patterns generate biological and psychological stresses that accelerate the progression of the disease.

Breaking this feedback loop requires identifying its origins. The body’s circadian clock is thought to act on 20% of all genes in the human genome, controlling when they turn on or off to manage processes including digestion, the immune system and our sleep-wake cycle.

Musiek had previously identified a specific protein, YKL-40, that fluctuates across the circadian cycle and regulates normal levels of amyloid protein in the brain. He found that too much of YKL-40, which is linked to Alzheimer’s risk in humans, leads to amyloid build-up, an accumulation that is a hallmark of the neurodegenerative disease.

Amyloid disrupts rhythmic brain functions

The cyclic nature of Alzheimer’s symptoms suggests that there are more circadian-regulated proteins and their associated genes involved beyond YKL-40. So in this latest study, Musiek and his colleagues examined gene expression in the brains of mice with accumulations of amyloid proteins that mimic early stages of Alzheimer’s, as well as those of both healthy, young animals and aged mice without amyloid accumulations. The scientists collected tissue at 2-hour intervals over 24 hours and then performed an analysis of what genes were active during particular phases of the circadian cycle.

They found that the amyloid accumulations threw off the daily rhythms of hundreds of genes in brain cells known as microglia and astrocytes in ways that were different from what aging alone caused. Microglia are part of the brain’s immune response, clearing away toxic materials and dead cells, while astrocytes have roles in supporting and maintaining communication between neurons. The affected genes are generally involved in helping microglial cells break down waste material from the brain, including amyloid.

While the circadian disruption didn’t entirely shut down the genes in question, it turned an orderly sequence of events into a scattershot affair that could degrade the optimal synchronicity of brain cells’ functions, such as clearing amyloid.

In addition, the researchers found that the presence of amyloid appeared to create new rhythms in hundreds of genes that do not typically have a circadian pattern of activity. Many of the genes are involved in the brain’s inflammatory response to infection or imbalances such as amyloid plaque build-up.

Musiek said that altogether the findings point to exploring therapies that target circadian cycles in microglia and astrocytes to support healthy brain function.

“We have a lot of things we still need to understand, but where the rubber meets the road is trying to manipulate the clock in some way, make it stronger, make it weaker or turn it off in certain cell types,” he said. “Ultimately, we hope to learn how to optimize the circadian system to prevent amyloid accumulation and other aspects of Alzheimer’s disease.”

As Pickleball Continues to Gain Players, Injuries Are Increasing

Woodard elected to National Academy of Medicine

Pamela K. Woodard, MD, head of the Department of Radiology and director of Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has been elected to the National Academy of Medicine — one of the highest honors in health and medicine. Election to the academy recognizes individuals who have demonstrated outstanding professional achievement and commitment to service.

Woodard, also the Elizabeth E. Mallinckrodt Professor of Radiology, is one of 100 new members elected to the academy this year. She was honored for her leadership as director of Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, one of the largest academic radiology departments in the U.S., ranking third in funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Woodard’s election reflects a distinguished career as a researcher and clinician — marked by major advances in the development and clinical translation of cardiac imaging techniques that have improved clinicians’ ability to diagnose and treat cardiovascular disease — as well as her dedication to inspiring the next generation of physician-scientists in the field.

“Dr. Woodard’s groundbreaking work in cardiothoracic imaging and her commitment to training radiologists have advanced imaging science and the practice of radiology in exceptional ways,” said David H. Perlmutter, MD, Executive Vice Chancellor for Medical Affairs, the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor and the George and Carol Bauer Dean of WashU Medicine. “Her election to the National Academy of Medicine is a well-deserved honor that reflects key contributions to improving patient care in the area of radiology. We’re so proud to celebrate this recognition with her and grateful for all she contributes to the WashU Medicine community.”

Among her accomplishments is the clinical translation of a technique to decrease motion artifact (an image disturbance due to movement) in MRI scans caused by a patient’s breathing. This advance has allowed three-dimensional MRI imaging to be used for diagnostic scans of cardiac patients. The first clinical use of the technique occurred at WashU Medicine.

She also led a team that has provided new tools to help doctors characterize atherosclerotic plaques, which are accumulations of fats and other materials in blood vessels that can cause cardiovascular events such as heart attacks or strokes. The nanoparticle-based PET imaging radiotracer her group developed selectively adheres to specific receptors in the plaques in the blood vessels, potentially allowing physicians to better identify their patients’ risk of stroke. Woodard has also led other first-in-human trials translating WashU-developed PET radiotracers into people.

Woodard is a pioneer in developing the use of multidetector spiral CT — a device that collects multiple CT images simultaneously — to detect pulmonary embolisms, which are potentially deadly blood clots that travel into the blood vessels of the lungs. Woodard worked on the technique as a resident at Duke University. She also was a principal investigator of the clinical trial that eventually established the imaging technique as the standard of care for diagnosing blood clots in the lungs.

A committed educator, Woodard has led the Training Opportunities in Translational Imaging Education and Research (TOP-TIER) program at MIR since its inception in 2017. The NIH-funded program trains radiology residents and fellows in advanced translational imaging research.

Woodard is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering, the American College of Radiology and the American Heart Association. She was awarded the Gold Medal from the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging in 2025, the Radiological Society of North America’s Outstanding Researcher award in 2021 and, in 2015, the Distinguished Investigator Award given by the Academy of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging Research, of which she is currently president. In 2024-2025 she served as president of the American College of Radiology.

Woodard earned her bachelor’s and medical degrees from Duke. She then completed an internship in internal medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She returned to Duke for her residency in radiology and came to WashU Medicine for a clinical fellowship in cardiothoracic radiology, before joining the WashU Medicine faculty in 1997.

Social conflict among strongest predictors of teen mental health concerns

Approximately 20% of American adolescents experience a mental health disorder each year, a number that has been on the rise. Genetics and life events contribute, but because so many factors are involved, and because their influence can be subtle, it’s been difficult for researchers to generate effective models for predicting who is most at risk for mental health problems.

A new study from researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis provides some answers. Published Sept. 15 in Nature Mental Health, it mined an enormous set of data collected from pre-teens and teens across the U.S. and found that social conflicts — particularly family fighting and reputational damage or bullying from peers — were the strongest predictors of near- and long-term mental health issues. The research also revealed sex differences in how boys and girls experience stress from peer conflict, suggesting that nuance is needed when assessing social stressors in teens.

“Understanding which youth are most likely to go on to develop larger mental health concerns before they experience strong functional decline is critical to mitigating potential damage,” said co-senior author Nicole Karcher, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at WashU Medicine. “By emphasizing prevention strategies free of labels and stigma, we can provide youth experiencing mental health concerns with tools to address risk factors that can negatively affect long-term mental health and well-being.”

A computational approach to mental health

The researchers analyzed data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study — a long-term, multisite study that is tracking the neurodevelopment of more than 11,000 U.S. children ages 9 to 16 from across the country, including a site based at WashU. The data gathered by the investigators include neuroimaging scans, psychological tests and personal and family mental health histories.

Using this data set, Karcher worked with co-senior author Aristeidis Sotiras, PhD, an assistant professor at WashU Medicine Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology and the WashU Medicine Institute for Informatics, Data Science & Biostatistics; coauthor Deanna M. Barch, PhD, the Gregory B. Couch Professor of Psychiatry at WashU; first author Robert Jirsaraie, a doctoral student in the Division of Computational & Data Sciences at WashU who is co-advised by Sotiras and Barch; and other colleagues to develop computational models to predict current and future mental health symptoms as well as changes in symptoms over time. They considered 963 predictors of mental health across nine broad categories, such as family dynamics, environmental factors (including peer relationships), demographic factors, and brain structure and function from neuroimaging data.

Sotiras noted that machine learning enables researchers to analyze such highly dimensional data and identify patterns that predict outcomes. “It’s a powerful way to move beyond single-factor explanations toward a more comprehensive, data-driven understanding of risk,” he said.

The team found that family conflict, particularly fighting and frequent criticism between family members, and reputational damage among peers were the strongest predictors of current mental health difficulties such as depression, anxiety or behavioral problems.

Neuroimaging data were among the least predictive variables in these models. This finding is consistent with results from a prior analysis by Jirsaraie, Barch, Sotiras and colleagues, published in Molecular Psychiatry, which used machine learning to build brain models of psychopathology based on neuroimaging data from 956 participants ages 8 to 22.

Biological sex emerged as a critical factor in the new study, with girls experiencing more mental health symptoms on average and a worsening of symptoms over time compared to boys. The study also picked up a subtle distinction between how girls experienced peer victimization versus boys: Girls suffered more from being victims of gossip and isolation, while the mental health of boys was more affected by aggression or hostility toward peers.

Jirsaraie noted that even the team’s best performing models explained only about 40% of individual outcomes, which, while high compared to similar algorithmic tools, indicate that more research is needed to gain a complete understanding of all the factors that influence mental health.

“As we’re developing better computational models, it’s important to make sure our predictions are grounded in biologically meaningful information,” Sotiras said. “Given enough data, these powerful tools can find patterns. As we move beyond brain imaging modalities to include other risk factors to better predict mental health trajectories, it’s a continuous effort to improve our data sets, increase our sample size and validate our model.”

Key factors influencing persistent psychotic-like experiences

Although data from brain imaging was not a strong predictor for mental health symptoms generally in this group of adolescents, for some conditions, it can be insightful. This was shown in an earlier analysis by Karcher, Barch and colleagues of ABCD data from more than 8,000 children, published in August in Nature Mental Health, which looked at the relationship between structural and cognitive changes in the brain during adolescence and the future risk of severe mental health disorders.

Specifically, the study looked at these brain changes over time in children ages 9 to 13 who reported psychotic-like experiences (PLEs). These are unusual thoughts and perceptions that, when they are persistent and distressing, have been tied to a greater risk of being diagnosed with a severe mental health disorder in adulthood, such as schizophrenia. The researchers found that the small subset of participants who had the most persistent and distressing PLEs had greater changes in brain structure — for example, decreases in cortical thickness, area and volume — and steeper declines on cognitive tests over time than those who experienced transient or no PLEs.

The study also found that these brain changes and declines in cognition may help explain the association between environmental risk factors, such as being exposed to financial adversity and unsafe neighborhoods, and a greater risk of persistent, distressing PLEs. According to the researchers, exposure to environmental stress may cause physical changes in the brain that then make a child more vulnerable to abnormal thoughts and perceptions.

Intervening early

Together, the findings highlight how social and environmental factors can impact adolescent brain development and contribute to mental health symptoms over time. Because they aren’t necessarily fixed, these factors are prime targets for intervention by parents, teachers, counselors and clinicians.

“The factors influencing mental health are complex, but this is ultimately a simple story,” Karcher said. “Adolescents are spending much of their time in these home and school environments, so interactions that take place there can have really large detrimental effects on mental health.”

On the flip side, these relationships can also have a buffering or protective effect. Being more mindful about the social environment of teens can lead to earlier detection and potential intervention around mental health issues, which become more prominent during this stage in life, Jirsaraie noted.

“Our findings can be very empowering for parents and teachers, as they have some control in mitigating the largest risk factors affecting the mental health of teens,” he said. “Resolving social conflicts could have a positive and lasting impact.”

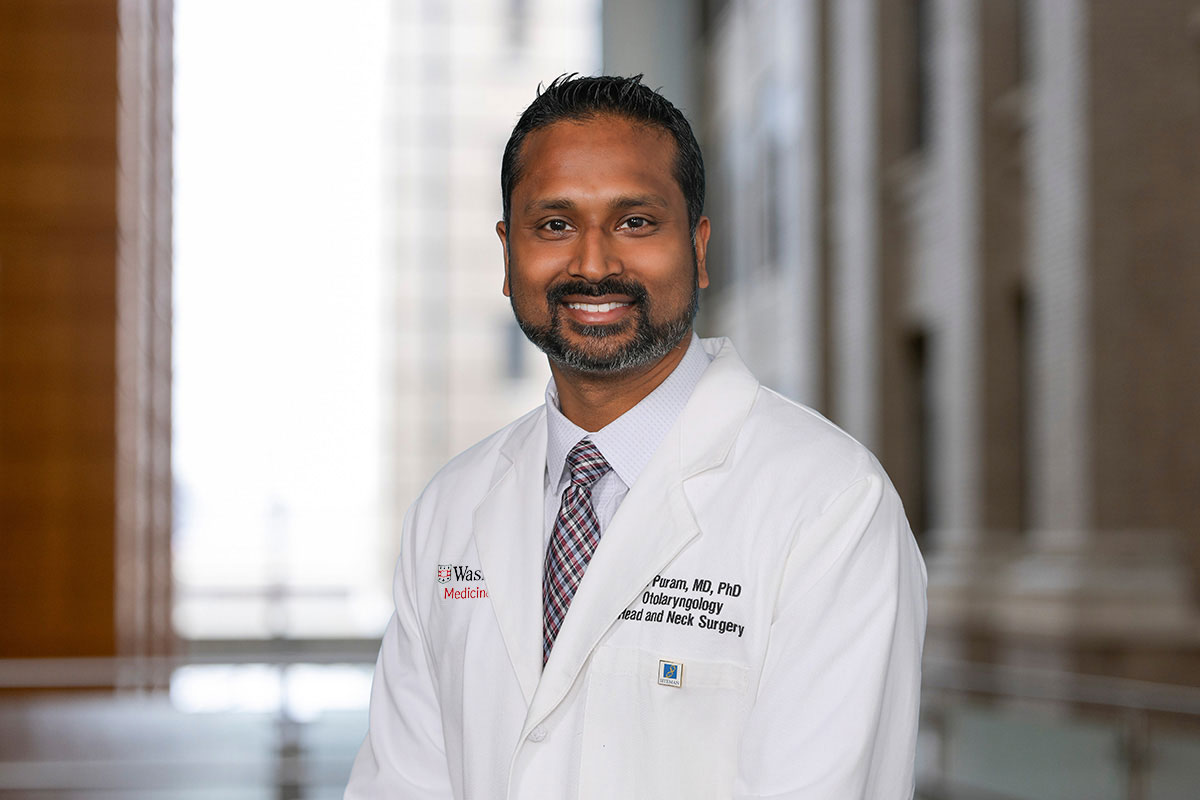

Puram named head of otolaryngology

Sidharth “Sid” V. Puram, MD, PhD, has been named the head of the Department of Otolaryngology — Head & Neck Surgery and the Lindburg Professor of Otolaryngology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. A nationally recognized physician-scientist specializing in head and neck cancer surgery, Puram currently serves as the Joseph B. Kimbrough Professor and director of the department’s Division of Head & Neck Surgery. He also is co-director of the Robert Ebert and Greg Stubblefield Head and Neck Tumor Center at Siteman Cancer Center, based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and WashU Medicine. Puram’s new appointment begins Nov. 1, 2025.

His research has advanced understanding of tumor growth, treatment resistance and metastasis in head and neck cancers — discoveries that have opened new options for treating these challenging tumors.

“Dr. Puram is an exceptionally talented physician-scientist and mentor who was unanimously selected by our leadership team from an outstanding pool of candidates,” said David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor and the George and Carol Bauer Dean of WashU Medicine, who announced Puram’s new appointment. “He will be leading a department that has always been esteemed but has grown in accomplishments and reputation in the last decade under the leadership of Dr. Craig Buchman. We believe Dr. Puram will inspire the otolaryngology team at WashU Medicine, with our partners at BJC HealthCare, to even greater impact and advance the science-based practice of care for patients with upper airways disorders in the coming decades.”

Puram’s research explores tumor heterogeneity — the complex ecosystem of diverse cells within a cancer and how they communicate with one another — a focus that has garnered significant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Understanding the cellular and genetic make-up of tumors can help scientists and clinicians identify and target the specific cells implicated in troubling behaviors seen in cancer such as tumor invasion, spread and resistance to therapy. His research has informed several innovative clinical trials and identified still other potential treatment avenues.

Detailing the diversity within tumors has pointed the way toward precision treatments for certain kinds of head and neck cancers and provides a foundation for developing therapies more tailored to the tumors of individual patients.

Through his leadership of the Division of Head & Neck Surgery at WashU Medicine, Puram has guided growth in both faculty and patient referrals while also establishing new collaborations with other departments to broaden the expertise offered to head and neck cancer patients with complex clinical needs. In his role as the inaugural co-director of the Robert Ebert and Greg Stubblefield Head and Neck Tumor Center, Puram has overseen a coordinated clinical program including head and neck specialists, oral health services, ancillary care and mental health care, among other services, with care coordination driven by patient navigation. This innovative, multidisciplinary approach is designed to improve patient outcomes by supporting patients throughout their cancer treatment while improving communication among the care team.

These programs reflect the department’s broader leadership in research and patient care. The department is the fifth-highest recipient of NIH research funding for otolaryngology departments. Each year, its physicians care for more than 120,000 patients and perform more than 11,000 surgeries, including nose and sinus operations; cochlear implants and other procedures to restore hearing; facial reconstruction surgeries; procedures to improve voice and swallowing; pediatric upper airway surgeries; and cancer surgeries.

“Otolaryngology at WashU Medicine is like no other in the U.S. in terms of its academic rigor and the collegiality of the faculty and researchers, so it is a great honor to have been selected to lead the department,” said Puram. “We have a fantastic team of physicians, researchers and trainees here who are absolutely committed to delivering the highest standard of care for our patients today and to carrying out rigorous research that will benefit the patients of tomorrow. Our team continues to push the boundaries through innovative surgical techniques and research projects that will disrupt traditional paradigms of care. I’m very excited to be able to carry that mission forward.”

As a head and neck cancer specialist, Puram is in the rare position as a physician of being both his patients’ surgeon and primary oncologist. With a particular focus on reconstructive surgery after the removal of head and neck cancer, he helps many patients return to their lives and minimize damage to key functions such as speech, swallowing, taste, hearing and smell.

Puram earned his bachelor’s degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned both his MD and PhD from Harvard Medical School in 2013. For his graduate research, Puram identified signaling pathways in brain cells that affect the shape of their dendrites, which are key recipients of information.

Puram chose otolaryngology as his medical specialty because it provided him the opportunity to perform a variety of anatomically intricate and challenging surgeries while also practicing as a cancer specialist. He completed a residency in otolaryngology in the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary/Harvard Combined Program in 2018. During his simultaneous postdoctoral fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital/MIT Broad Institute, Puram published the first single-cell atlas of head and neck cancers. He then completed his training with a clinical fellowship in microvascular reconstruction/head and neck surgical oncology at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – James before coming to WashU Medicine in 2019.

Puram serves on the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research special grants review study section. He is also on the editorial boards of Surgical Oncology Insight, Head & Neck and Frontiers in Oncology. Puram has been recognized by his peers for his teaching, science and clinical skills. He received the American Society for Clinical Investigation Young Physician Scientist Award in 2020 and was named a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons in 2021. He received the Department of Otolaryngology — Head & Neck Surgery Faculty Teaching Award earlier this year.

Klinman recognized as outstanding early-career scientist

Eva Klinman, MD, PhD, an instructor in the Department of Neurology at WashU Medicine, has been honored by online publication STAT News as a 2025 STAT Wunderkind. Wunderkinds are selected by STAT’s editorial staff to recognize and celebrate the achievements of early-career scientists and researchers who are making significant contributions to biomedical science. Through the Wunderkinds program, STAT spotlights the next generation of scientific leaders and underscores the vital role of young researchers in driving progress and innovation.

Klinman joins a distinguished cohort of 29 promising young scientists celebrated for their innovative research, potential for future impact and overall excellence in their respective areas of expertise. Klinman’s research focuses on the underlying mechanisms of brain aging that result in age-related neurodegeneration and dementia, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. She has received mentorship at WashU Medicine from leading scientific researchers in developmental biology, aging and movement disorders, which she has used to shape her own research and to educate the next generation of scientists.

As a Wunderkind, Klinman was invited to participate in the annual STAT Summit, a high-profile event that brings together leaders and innovators in health, medicine and biotechnology. The 2025 STAT Wunderkinds cohort was announced Oct. 15, the first day of the two-day summit. In addition to this formal recognition, honorees had the opportunity to connect and engage with fellow researchers and potential collaborators to explore new opportunities for advancing their work.