WashU Medicine’s fellow-to-faculty programs nurture growth of talented early-career scientists

Alex Francette, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Cell Biology & Physiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, already had big plans when he arrived on campus in November 2024. The first fellow in an innovative new program in the department, he would have the opportunity to pursue an independent research program before transitioning into a tenure-track faculty position. Francette had impressed the hiring committee with his proposed project to decipher how cellular dysregulation in disease can be caused by variations in specific protein molecules.

It was an ambitious plan to investigate how the instructions in DNA are faithfully turned into RNA “messages” that guide the activity of cells. Mistakes in this process can lead to cancer or other diseases. “I quickly realized that with the mentorship and the sophisticated core facilities available to me in this incredible environment, I could shift gears upward to do even more than I’d originally hoped,” he said.

The department’s fellowship program, called RISE (Retention and Inclusion of Scholars for Excellence), is designed to match talented early-career scientists with WashU Medicine’s unparalleled research infrastructure, dedicated faculty mentors and culture of scientific audacity — where researchers are encouraged to take on the toughest problems and the most complex questions. Unlike traditional postdoctoral roles, where researchers work in a senior faculty member’s lab before eventually leaving to start their own lab elsewhere, RISE fellows start developing a fully independent research program from day one. If successful, they transition directly into tenure-track faculty positions at WashU Medicine in three years, with uninterrupted momentum.

The commitment to young researchers’ career paths is what sets WashU Medicine’s fellow-to-faculty initiatives apart, according to David Piston, PhD, the Edward J. Mallinckrodt, Jr. Professor and head of the Department of Cell Biology & Physiology, who notes that similar fellowship programs have been launched in the Department of Genetics and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics.

“We’re after people who are very desirable for top-tier research institutions, and they have a lot of choices,” said Piston. The opportunity for independence and career fast-tracking to a faculty position makes the program a powerful attraction for talented young scientists, he added. “We are asking these fellows to stake a key part of their career with us. By linking their fellowship success to a faculty position, we signal that we have skin in the game, too.”

Scientific resources to RISE to the occasion

Francette is a first-generation doctoral graduate who earned his PhD in molecular biology at the University of Pittsburgh in 2024. At WashU Medicine, his mentorship team spans departments and specialties, giving him access to expertise in messenger RNA (mRNA), imaging and mammalian tissue culture, all essential to his research. His new lab is a short walk from both the McDonnell Genome Institute, where he can call on specialized assistance to analyze his large data sets of transcription elongation molecules, and the world-class microscopy facilities of the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging, where he can observe the effects of transcription variation in his cell cultures. All told, it is a veritable candy store for an early-career molecular biologist with Francette’s aspirations.

Even so, launching a lab nearly from scratch can be daunting. Not everyone is ready for it, said Piston, who felt that Francette stood out for his scientific maturity.

“He has no reluctance to tackle difficult questions and think carefully about what he needs to do to get answers to them,” said Piston of Francette. “Our goal in the department is to ensure he has what he needs to do that.” The program provides Francette with start-up funds that he has used to hire a lab technician and purchase the equipment and supplies he needs to fill out his lab space.

Piston noted that the program’s mentorship and resources, combined with Francette’s energy, are already bearing fruit: The fellow has two papers coming out this year and a third in the works.

Fellows united

Francette is navigating this path with the support of other fellows in similar programs at WashU Medicine. Shortly after moving to St. Louis, he connected with Jackie Pelham, PhD, the inaugural Gerty and Carl Cori Fellow in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics. Their connection led to “Fellows United,” an informal support group that also includes Juan Macias-Velasco, PhD, the first fellow in the Department of Genetics’ new fellow-to-faculty program.

“We have a tight-knit community and support one another as we’re starting our careers,” said Pelham, who earned her PhD in biochemistry and biophysics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and moved to St. Louis shortly thereafter.

Matt Miller

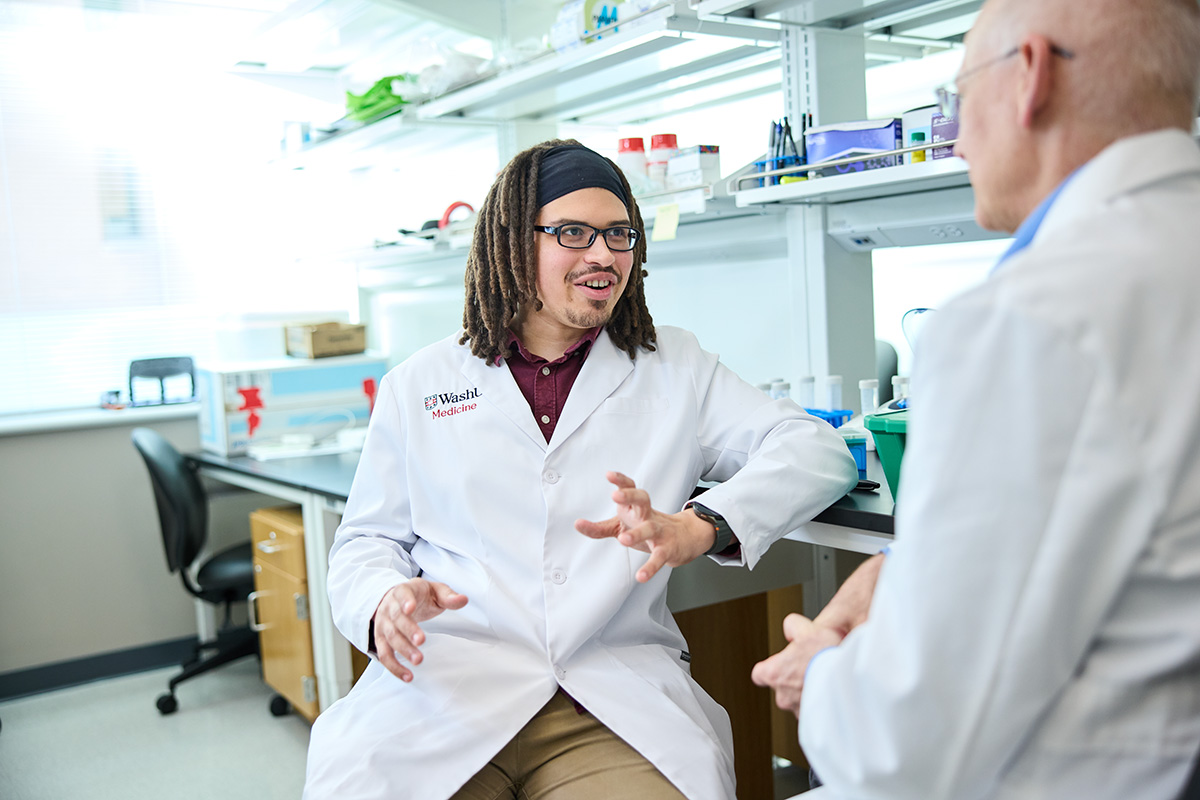

Matt MillerJackie Pelham, PhD (left), the inaugural Gerty and Carl Cori Fellow in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, examines an assay with assistant professor Alex Holehouse, PhD (right), a faculty mentor.

Pelham came to WashU Medicine to continue her work on intrinsically disordered proteins — protein regions that lack a stable 3D structure and that are key components of the body’s circadian clock. WashU Medicine’s strengths in both disordered proteins and how circadian rhythms impact human health made it an obvious destination to launch her independent career.

Alex Holehouse, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, said that Pelham is a recognized leader in her field and has built a research program in just three years that is on par with those of well-established faculty, accomplishments that were recognized with WashU Medicine’s Rosalind Kornfeld Postgraduate Research Trainee Leadership Award. Pelham’s presence is “a net win, unambiguously, in every dimension,” said Holehouse, adding that she is an active contributor to the department in training students in molecular biology and mass spectrometry and in establishing a group, open to all faculty and students, to provide networking and career advising for women in biochemistry and biophysics.

The model is spreading. The newly launched Department of Genetics fellow-to-faculty program aims to prepare fellows not just as scientists but as future leaders. The first recruit, Macias-Velasco, earned his PhD at WashU in computational and systems biology, a field that uses sophisticated statistical approaches to understand human genetics and the development of disease.

“In academia, we’re trained to be good scientists,” said Ting Wang, PhD, the Sanford and Karen Loewentheil Distinguished Professor of Medicine and head of the Department of Genetics. But researchers who lead their own labs also wear other hats, he noted, such as those of manager, motivator and accountant. Wang encourages researchers in his department to take courses and workshops on these topics. “We are in positions of leadership, and we are training the next generation of scientists,” he said. “We want to give fellows like Juan support and opportunities so they can grow into that leadership role even faster.”

Matt Miller

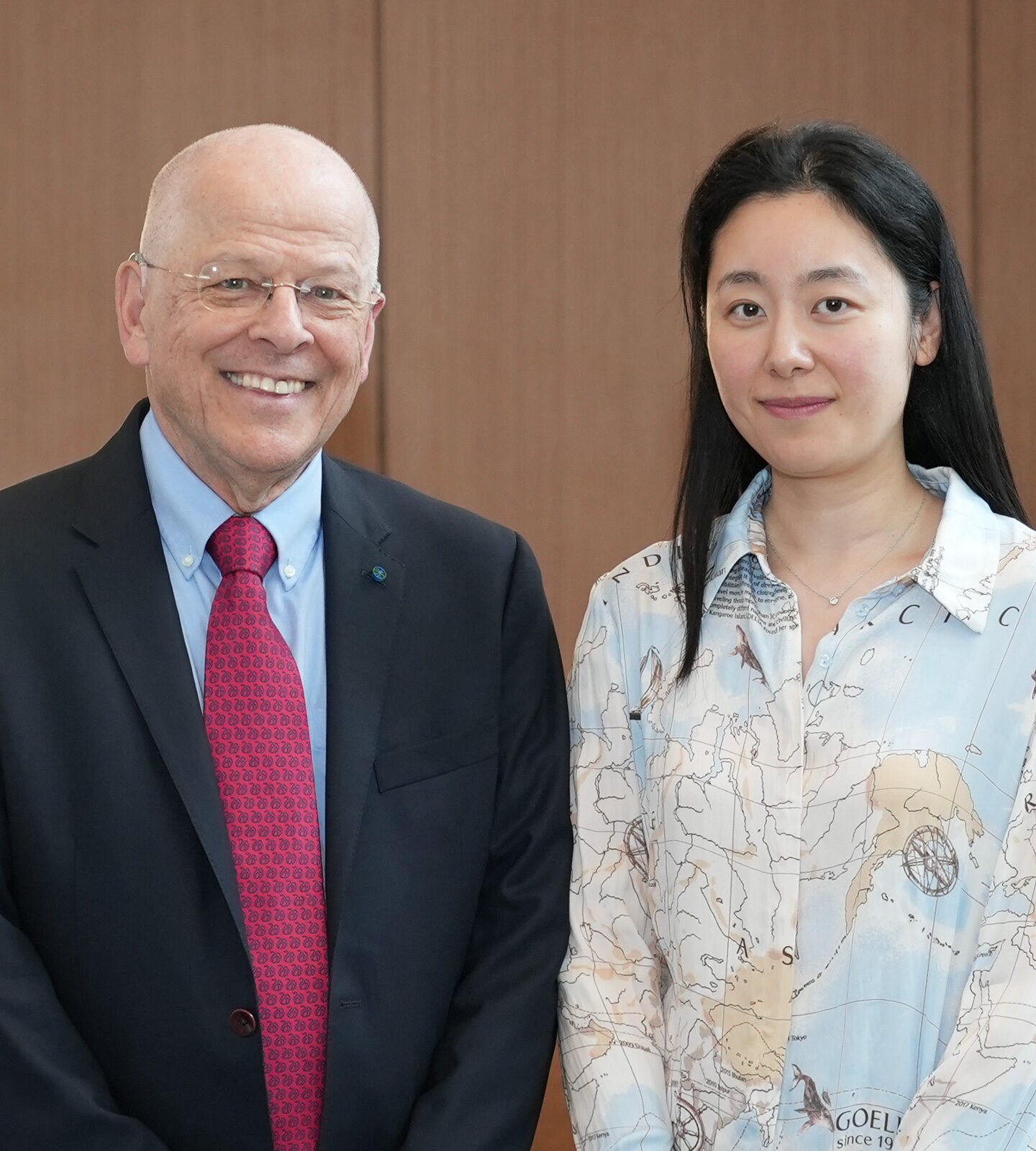

Matt MillerJuan Macias-Velasco, PhD (left), the inaugural Dean’s Fellow to Faculty participant in the WashU Medicine Department of Genetics, reviews data with Ting Wang, PhD (right), the Sanford and Karen Loewentheil Distinguished Professor of Medicine and head of the department.

To that end — and in addition to running his own projects — Macias-Velasco manages a team of graduate and undergraduate students working in his lab and helps oversee elements of the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC), an NIH-funded multi-institute project centered at WashU Medicine for which Wang is the principal investigator. The initiative aims to improve on the Human Genome Project, which produced — with substantial contributions from WashU Medicine — the standard genome reference sequence for scientists studying gene function and variation. The reference genome was developed from the DNA of a relatively small number of people, with 70% of its information derived from a single individual. The consortium aims to broaden that base to better capture the normal variation of human genetics by including more DNA samples.

Macias-Velasco is passionate about the power of computational biology and its potential to find answers within the genome to important questions about human health. He said that a conversation he had with a personal hero of his — Maynard Olson, PhD, a former WashU Medicine geneticist who laid the foundations for the Human Genome Project — has shaped how he thinks of his fellowship.

“He told me that one of the strengths of WashU Genetics was that it was willing to put its faith in people and their research,” said Macias-Velasco. “These fellow-to-faculty programs are a way that we can reach for those high-risk, high-reward outcomes, while being integrated into the broader WashU Medicine research community. People are holding on to us, while we reach out just a little bit further.”

A growing magnet for talent

For department chairs like Ben Garcia, PhD, the Raymond H. Wittcoff Distinguished Professor and head of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, who worked to establish the Cori Fellowship, the fellow-to-faculty pathway is proving to be more than an experiment. It’s a recruitment advantage, a retention strategy and a catalyst for scientific boldness.

“Programs like this are a magnet for the kinds of ambitious and talented young scientists that we want to have at WashU Medicine,” said Garcia. “Our strengths accelerate their science, but that momentum carries us all forward.”