Researchers find key to stopping deadly infection

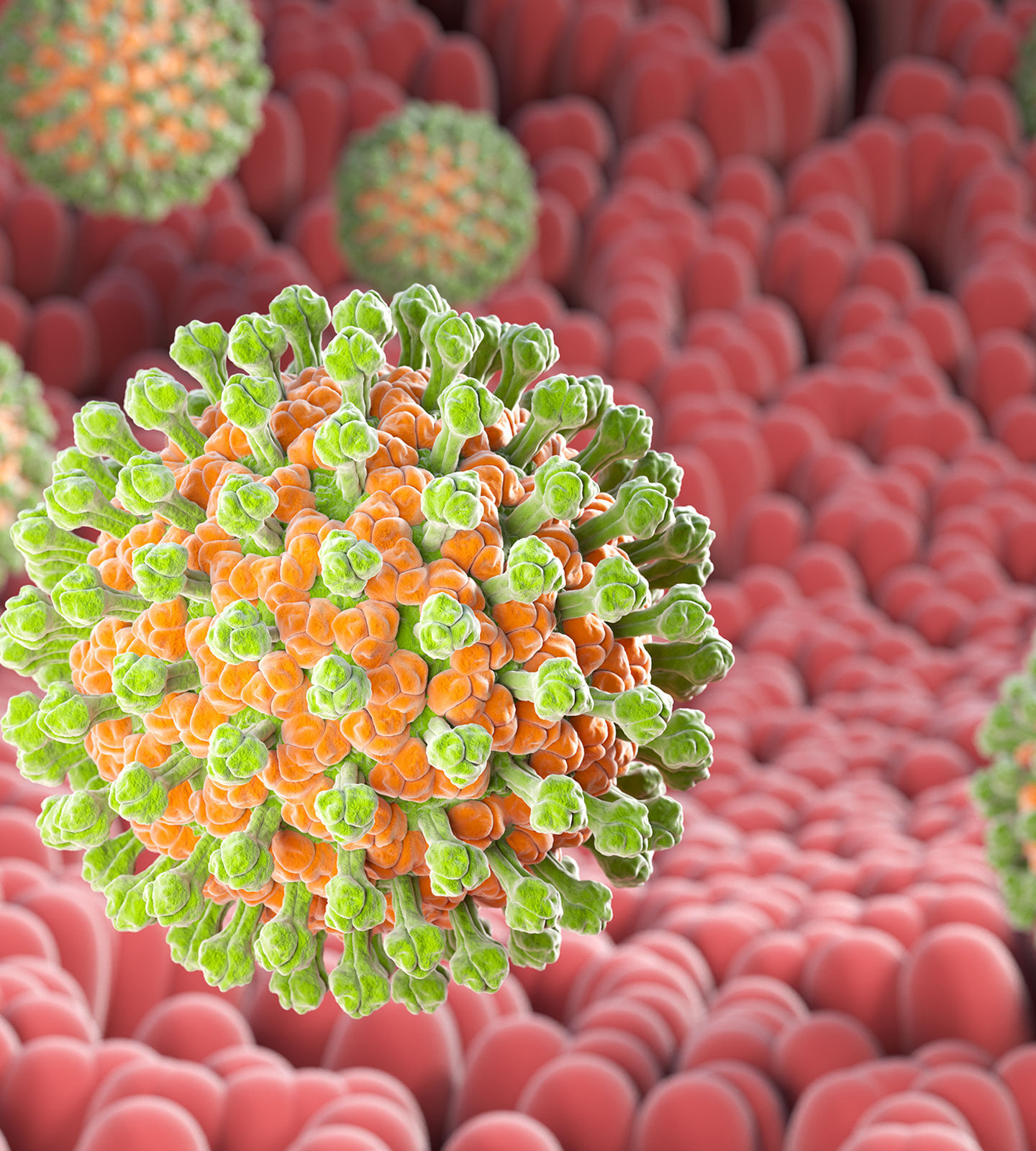

Rotavirus causes severe dehydrating diarrhea in infants and young children, contributing to more than 128,500 deaths per year globally despite widespread vaccination efforts. Although rotavirus is more prevalent in developing countries, declining vaccination uptake in the United States has resulted in increasing cases in recent years.

New research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has identified a key step that enables rotavirus to infect cells. The researchers found that disabling the process in tissue culture and in mice prevented infection. This discovery opens up new avenues for therapeutic intervention to treat rotavirus and other pathogens that rely on the same infection mechanism.

The results were published in PNAS.

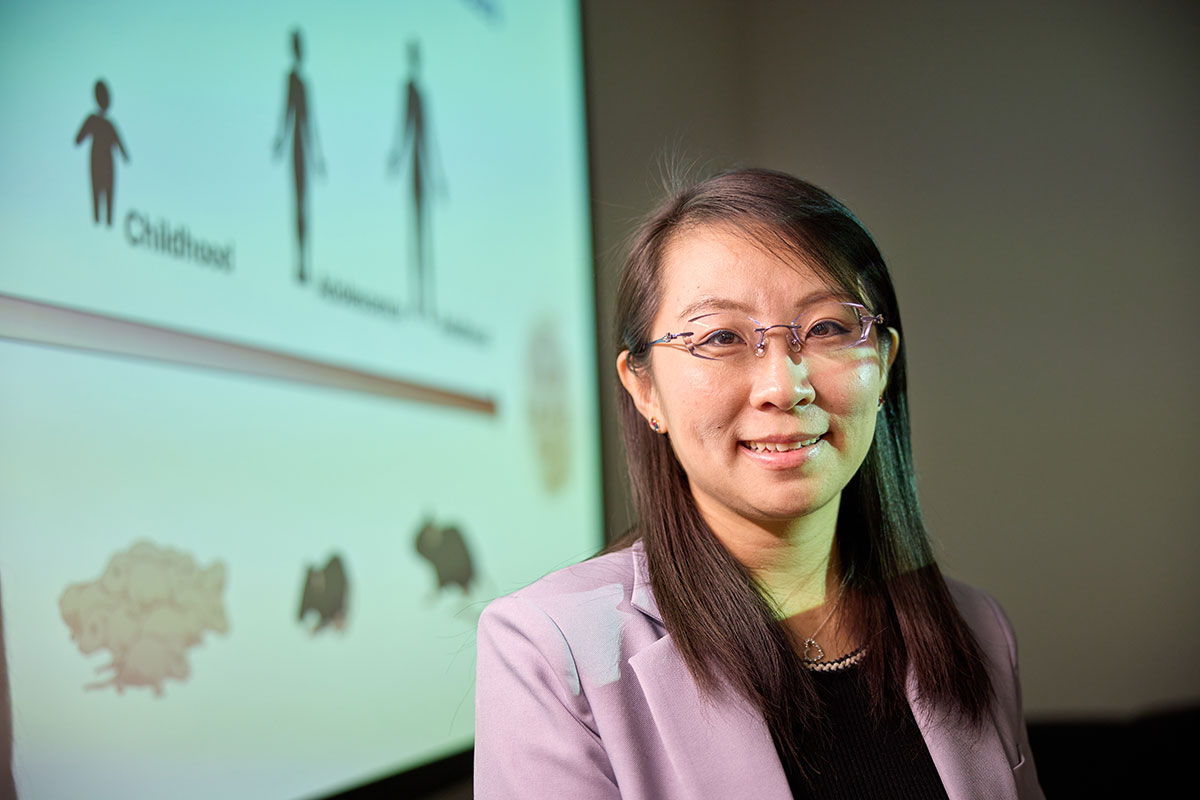

“Rotavirus kills infants and children, young people who never had a chance at life,” said Siyuan Ding, PhD, an associate professor of molecular microbiology at WashU Medicine. “That’s why we want to develop effective therapeutics, even though we already have vaccines that we can use. Not all kids receive the vaccine, and this virus is very infectious. Once a child has the virus, there’s currently no treatment; we can only manage the symptoms.”

Enzyme as entry code

To identify a possible treatment, Ding and his collaborators focused on features of the body’s cells that can be leveraged to protect against viral infection. This strategy, Ding said, may be less likely to trigger drug resistance than targeting the virus itself and has the potential to work on multiple diseases because it is based on shared infection routes, not disease-specific traits.

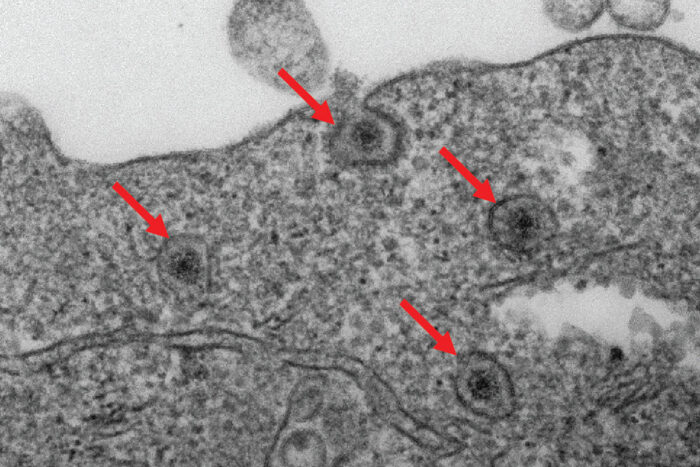

When a rotavirus particle burrows through the outer wall of a cell, it isn’t immediately free to infect the cell. Instead, the virus emerges inside a tiny cell compartment called an endosome.

The researchers identified an enzyme in cells, called fatty acid 2-hydroxylase (FA2H), that is essential to rotavirus breaking out of endosomes and fully infecting cells. Using advanced gene editing techniques, they removed the FA2H gene from human cells and found that viruses remained trapped in endosomes and could not replicate effectively. In other words, disabling FA2H prevented infection from the very beginning.

Ding Lab

Ding LabTo confirm these results in animal models, the researchers created genetically modified mice specifically missing the FA2H enzyme in the cells lining the small bowel. These mice showed significantly fewer symptoms when infected with rotavirus compared to normal mice, demonstrating the importance of FA2H in viral infections.

Unlike vaccines that typically cue the body to produce antibodies that block pathogens from entering cells in the first place, disabling FA2H intervenes in the normal course of infection to craft a complementary line of host-based cellular defense against rotavirus and similar infections.

“Viruses are dependent on hosts, so we’re preventing infection by stopping them from using the host’s machinery,” Ding said. “We didn’t really know how this enzyme, FA2H, worked until this study, but now we’re seeing that the same process aids other pathogens, such as Junín virus and Shiga toxin, suggesting a common ‘entry code’ used by multiple disease-causing agents.”

Now that Ding and his collaborators have identified this pathway as a broadly exploitable entry mechanism, they can start testing drugs that duplicate the effect of FA2H gene editing.

Body’s garbage-collecting cells protect insulin production in pancreas

Approximately 9.5 million people globally live with Type 1 diabetes, a chronic autoimmune disease where T cells from the body’s immune system destroy insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, which are needed to control blood-sugar levels. Daily insulin injections and continual blood glucose monitoring help control the disease, but there is no cure or preventive.

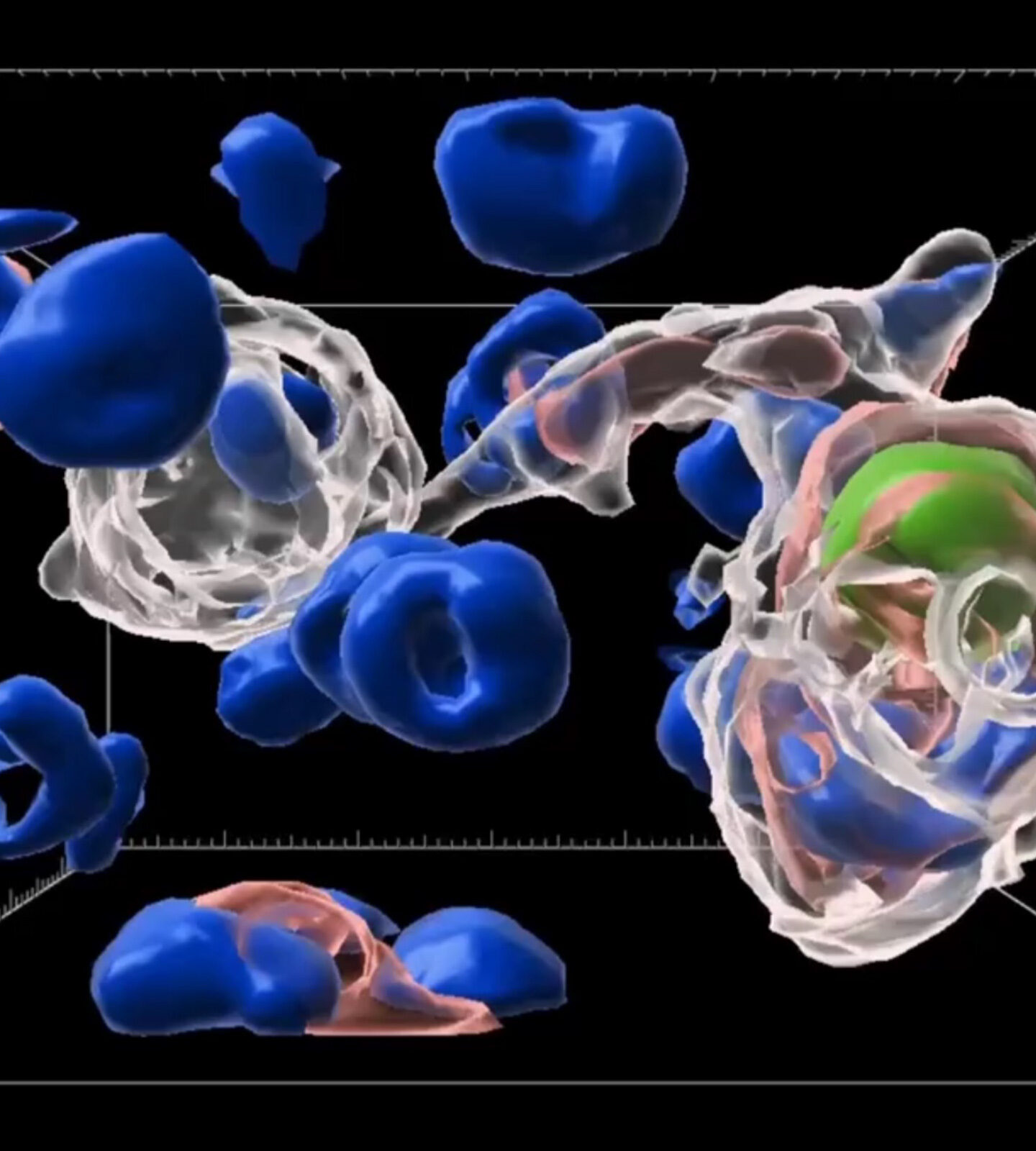

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found a group of immune cells in the pancreas that can render T cells inactive, protecting insulin-producing beta cells and preventing Type 1 diabetes from developing in mice otherwise destined to develop the disease. The newly identified cells are a type of macrophage — immune cells that consume dead cells throughout the body to help keep tissue healthy.

The researchers revealed that the protective macrophages, which they dubbed efferocytic macrophages, or eMacs, acquired the ability to silence T cells after consuming dead cells in the pancreas.

The findings appear in Nature on October 1.

“Now we know the identity of the cells that can make T cells less responsive,” said senior author Kodi Ravichandran, PhD, the Robert L. Kroc Professor of Pathology & Immunology and a BJC Investigator at WashU Medicine. “If we can mimic the series of events responsible for converting macrophages into e-Macs, we could potentially boost them to help prevent or control Type 1 diabetes and even other autoimmune diseases.”

Garbage-engulfing immune cells protect

The pancreas contains clusters of cells called beta cells whose job is to produce insulin, a hormone that’s critical for keeping blood-sugar levels in a safe range. A small number of beta cells routinely die to reduce inflammation and keep tissues healthy, a natural process that happens in cells throughout the body.

Macrophages then engulf and digest the cellular debris in a process called efferocytosis. These garbage-eating cells also play an important role in influencing the behavior of T cells throughout the body. The researchers wondered if such macrophages play a role in helping to maintain the health of the pancreatic tissue by influencing the immune system.

“How macrophages engage and consume cellular garbage can influence what is happening in the cellular neighborhood,” said Ravichandran, also a co-corresponding author on the study. “And this also guides how macrophages interact with T cells.”

For example, macrophages can activate T cells to help fight an infection after consuming a dying infected cell. In the case of naturally dying beta cells in the pancreases of mice, the researchers found that after engulfing the cells, the eMacs shifted their behavior to deactivate T cells, protecting the surrounding healthy beta cells from attack. The researchers surmised that the macrophages essentially acquired this behavior after consuming the dead beta cells and that if this can be mimicked, then the healthy beta cells could be protected from attack by T cells in the context of diabetes.

In the study, the researchers administered a single low dose of a chemotherapy drug, streptozotocin, to mice prone to Type 1 diabetes in an experiment designed to kill a few cells in the pancreas, mimicking the natural process of cell death that happens in healthy people when maintaining the health of their organs. They found a greater proportion of e-Macs among the macrophages in the pancreases of mice treated with streptozotocin compared with those of mice given a placebo. Streptozotocin-treated mice were protected from developing diabetes for more than 40 weeks, while mice given the placebo became diabetic by 20 weeks and did not survive past 30 weeks.

The researchers hope to find ways to boost e-Macs in humans for therapeutic use, Ravichandran said. They also identified a subset of macrophage analogs to the mouse e-Macs in the pancreases of deceased human organ donors.

“Because these trash-disposing pancreatic macrophages become protective against Type 1 diabetes, we are intrigued by the possibility of leveraging their disease-preventing properties in people at high risk for this condition,” Ravichandran said.

Future studies aim to focus on increasing the fraction of e-Macs in the pancreas with the goal of helping people with a family history of Type 1 diabetes to prevent the disease.

Other WashU Medicine collaborators on the study included first and co-corresponding author Pavel Zakharov, PhD, an instructor of pathology & immunology; Xiaoxiao Wan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pathology & immunology; Eynav Klechevsky, PhD, an associate professor of pathology & immunology; and the late Emil R. Unanue, PhD, who died before seeing the study’s completion. Unanue, a 1995 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award winner, was a pioneer in describing the interactions between T cells and presenting cells — immune cells that display a sample of a potential threat on their surface – that make it possible for the former to recognize and respond to foreign invaders.

What Are Senescent Cells?

WashU Medicine launches program to grow the next generation of leaders in health care

Kim and Tim Eberlein receive Harris Award

Toxins, tech and tumors: Is modern life fueling the rise of cancer in millennials?

Want to Know Your Future Breast-Cancer Risk? Just Ask AI

$5 million funds innovation of more-potent opioid overdose antidote

The opioid epidemic claims more than 50,000 lives annually in the U.S., highlighting the urgent need for lifesaving interventions. Although naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan, effectively restores normal breathing during an overdose, its effects are short-lived and often require multiple doses. Meanwhile, emerging, more dangerous opioids threaten naloxone’s lifesaving effectiveness.

A team of researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Stanford University and the University of Florida had previously identified a compound that makes naloxone more potent and longer lasting without worsening withdrawal symptoms. Now, with a $5.2 million grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the researchers aim to develop the newly identified compound into a drug by combining it with naloxone into a single formulation that can be tested in future clinical trials.

“As new, more-potent opioids take to the streets, reviving people from overdose is becoming more challenging,” said Susruta Majumdar, PhD, a professor of anesthesiology at WashU Medicine and the principal investigator on the new project. “To get ahead of these dangerous opioids, we urgently need more powerful antidotes. This funding support from NIH is critical for expediting the drug development timeline, making it possible to bring new treatments to people within five years.”

A better naloxone

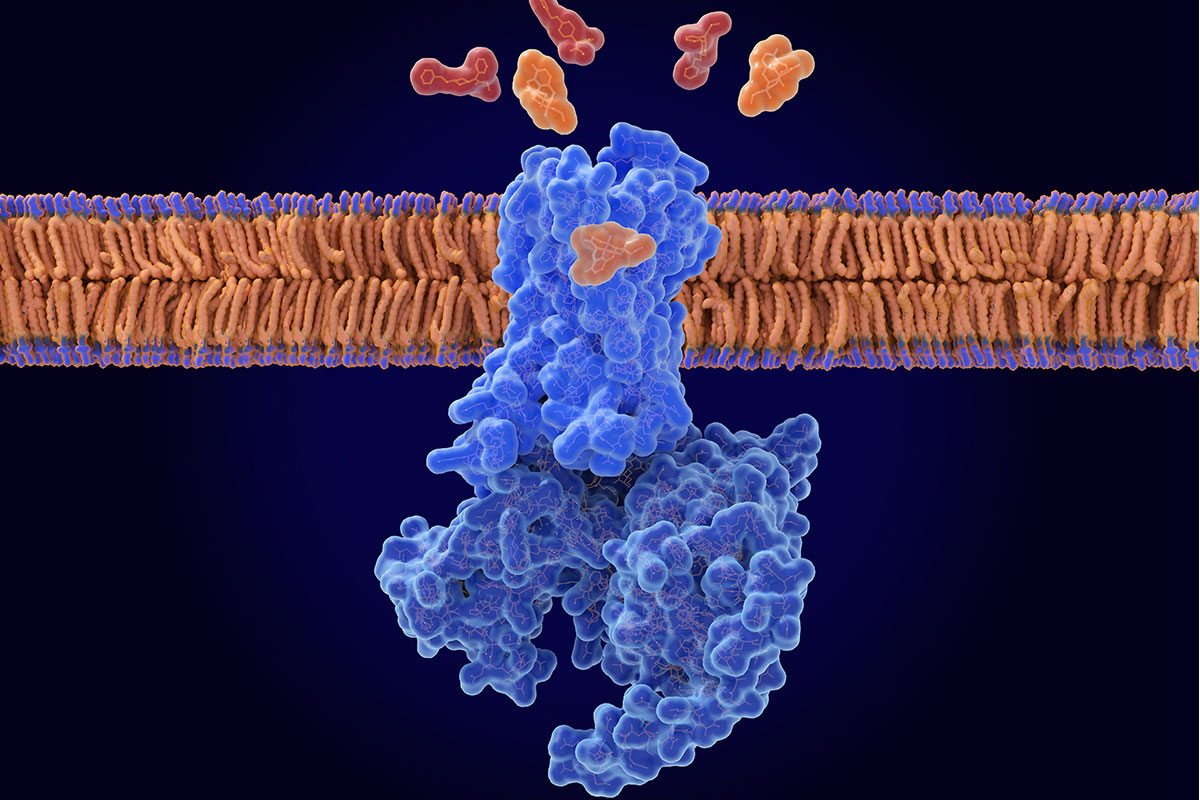

Opioids such as oxycodone and fentanyl bind to a pocket on the opioid receptor, a receptor found primarily on neurons in the brain. The binding triggers a cascade of events that reduce pain perception, induce a sense of euphoria and slow down or, in the case of an overdose, stop breathing. Naloxone — available as an over-the-counter nasal spray or injectable — is an opioid, but unlike other drugs in its class, it doesn’t activate the opioid receptor when it slips inside its binding pocket. By displacing problematic opioids from the pocket, naloxone can restore normal breathing to reverse an overdose. But naloxone has a shorter half-life than other opioids, such as fentanyl, so it wears off sooner. This means any circulating fentanyl molecules can re-attach to and re-activate the receptor, causing the overdose symptoms to return.

The research team — led by Majumdar; Brian K. Kobilka, PhD, a professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford University; and Jay P. McLaughlin, PhD, a professor of cellular and systems pharmacology at the University of Florida College of Pharmacy — previously found a molecule that keeps naloxone in the binding pocket longer, strengthening its ability to reverse an opioid overdose.

In a study published in 2024 in Nature, the researchers determined that in the presence of the new molecule, which they dubbed compound 368, naloxone stayed in the binding pocket at least 10 times longer than without the compound in experiments performed in cells. As a negative allosteric modulator (NAM) of the opioid receptor, compound 368 adjusts the body’s response to drugs that bind to the opioid receptor by fine-tuning the activity of drug receptors. The researchers also found that the addition of the compound boosted naloxone’s potency without worsening withdrawal symptoms in mice exposed to opioids. Such symptoms, including pain, chills, vomiting and irritability, can be so severe that people resume opioid use to alleviate them, perpetuating the cycle of addiction.

With the new funding, the researchers aim to develop a naloxone-enhancing 368 compound that can be administered intranasally or intravenously with naloxone. Their work will focus on improving the compound’s solubility and size to ensure it dissolves properly in the bloodstream and can reach the brain effectively. After optimizing the compound’s drug-like properties, they will test in mice if it enhances naloxone’s ability to counteract opioid overdoses without worsening withdrawal symptoms, paving the way for future testing in clinical trials.

“Such funding from the NIH is critical for accelerating the transition of discoveries like ours from the lab to clinical use,” said Majumdar, who is a member of the Center for Clinical Pharmacology in the Department of Anesthesiology. “We are motivated to work exceptionally fast due to the speed with which opioids get stronger and more dangerous.”

Barnes-Jewish Hospital unveils state-of-the-art patient care tower

Plaza West Tower, the new 16-story patient care tower at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, will welcome patients beginning in October. The tower will provide private rooms for heart and vascular patients, advanced imaging and the latest in surgical preparation and recovery. Plaza West Tower is designed to enhance the experience for patients and their families under the expert care of WashU Medicine physicians and BJC HealthCare clinical teams.

As a major referral center in the Midwest, and the fifth largest hospital in the country, Barnes-Jewish Hospital provides advanced care for patients with complex conditions, making facilities like the Plaza West Tower vital. Internationally recognized WashU Medicine physicians lead this effort, driving innovation through clinical expertise, pioneering new therapies and advancing research that shapes the future of care. Together, BJH and WashU Medicine also play a significant role in training the next generation of health care professionals.

The new state-of-the-art facility offers 224 private inpatient rooms and 56 private intensive care unit rooms, advanced imaging and the latest in surgical preparation and recovery. WashU Medicine physicians serve as the exclusive physician providers at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where they bring world-renowned expertise — informed by the latest research discoveries — to the care of patients with the most complex medical conditions.

“BJC and WashU Medicine are where patients turn when answers can’t be found elsewhere,” said Nick Barto, president of BJC Health System. “The Plaza West Tower represents the power of academic medicine combined with our unwavering commitment to elevating patient care and improving the health of the communities we serve. It is an outstanding beacon in the community of all BJC and WashU represent.”

Barnes-Jewish Hospital, WashU Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Missouri Baptist Hospital’s Graduate Medical Education consortium is one of the largest in the United States offering 111 accredited programs and providing 1,476 residents and fellows the opportunity to train alongside specialists who are driving innovation and shaping the future of medicine.

“Plaza West Tower strengthens the ability of WashU Medicine and BJC to deliver world-class care,” said Paul Scheel, MD, CEO of WashU Medicine Physicians and president of WashU Medicine & BJC HealthCare Physician Provider Organization. “In this new space, WashU Medicine physicians will work seamlessly with multidisciplinary care teams, providing patients with expert, coordinated treatment — all in a supportive environment.”

A key benefit of Plaza West Tower will be the expansion of the critical care bed space for patients awaiting or recovering from advanced treatments including heart transplants, valve repairs or replacements, and minimally invasive procedures. In addition, state-of-the-art imaging capabilities and utilization of the latest technologies will improve surgical flow and enhance patient experience.

“The growing demand for critical care requires facilities that are as sophisticated and innovative as the care that we offer,” said John Lynch, MD, president of Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “The enhancements in Plaza West Tower are designed to foster collaboration among caregivers, which ultimately benefits our patients.”

The new tower is also designed to accommodate surges in patient volume and the need for isolation in the event of future pandemics. Frontline staff, including nurses, infection-prevention specialists and housekeeping teams, contributed their expertise to plans for the new tower.

Noteworthy design elements of Plaza West Tower also include:

- Private inpatient rooms designed with heart and vascular patients in mind

- Advanced bedside technology, allowing caregivers to spend more time with patients

- Family-friendly spaces to keep loved ones close and comfortable

- A family area with kitchenette, rest areas, showers, and laundry room

- A new cafeteria

- Two outdoor rooftop gardens

- Panoramic views of Forest Park from quiet seating areas on every inpatient floor

- A calming environment with natural light, art and views — all evidence-based elements for faster healing and reduced stress

More than 3,700 architects, engineers, project managers, skilled trades men and women, apprentices and interns were engaged in the construction of the tower, providing significant economic impact to the region in addition to the clinical and patient benefits the project brings.

Plaza West Tower is located on the site of the former Queeny Tower and is part of BJC HealthCare’s Campus Renewal, a long-term vision to transform the Washington University Medical Campus through new construction and renovations, with an overall focus on improving the experiences of patients and families. To date, the phases of the Campus Renewal Project have had an economic impact of nearly $2 billion, adding to the more than $20 billion total economic impact by BJC Health System across the communities BJC serves.

The design of the tower complements Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s Parkview Tower and the St. Louis Children’s Hospital expansion, which opened in early 2018, and completes the unified architecture and skyline for the Washington University Medical Campus from Forest Park Avenue to Barnes-Jewish Plaza.

Barnes-Jewish Hospital is ranked as the number one hospital in Missouri by U.S. News & World Report.

Novel way to ‘rev up’ brown fat burns calories, limits obesity in mice

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a novel way brown fat — an energy-burning form of fat — can rev the body’s metabolic engine, consuming cellular fuel and producing heat in a way that improves metabolic health. The study, in mice, reveals new avenues to exploit brown fat to treat metabolic diseases, such as insulin resistance and obesity.

The study is published Sept. 17 in Nature.

Brown fat is known for its ability to turn energy (calories) from food into heat. In contrast, white fat stores energy for later use while muscle makes energy immediately available to do work. Brown fat’s heat production helps the body stay warm in cold temperatures, and exposure to cold can increase brown fat stores. Researchers have proposed that activating brown fat could support weight-loss efforts by boosting calorie burn.

“The pathway we’ve identified could provide opportunities to target the energy expenditure side of the weight loss equation, potentially making it easier for the body to burn more energy by helping brown fat produce more heat,” said senior author Irfan Lodhi, PhD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism & Lipid Research at WashU Medicine. “Boosting this kind of metabolic process could support weight loss or weight control in a way that is perhaps easier to maintain over time than traditional dieting and exercise. It’s a process that basically wastes energy — increasing resting energy expenditure — but that’s a good thing if you’re trying to lose weight.”

A back-up heater in brown fat

The traditional understanding of brown fat’s heat production involves mitochondria —power plants within the body’s cells. Scientists have long known that mitochondria in brown fat have a method of disengaging from fuel production and instead producing heat, via a molecule called uncoupling protein 1. Yet they have also known that mice with brown fat that lack uncoupling protein 1 are still able to burn energy and produce heat, pointing to the existence of back-up burners in cells.

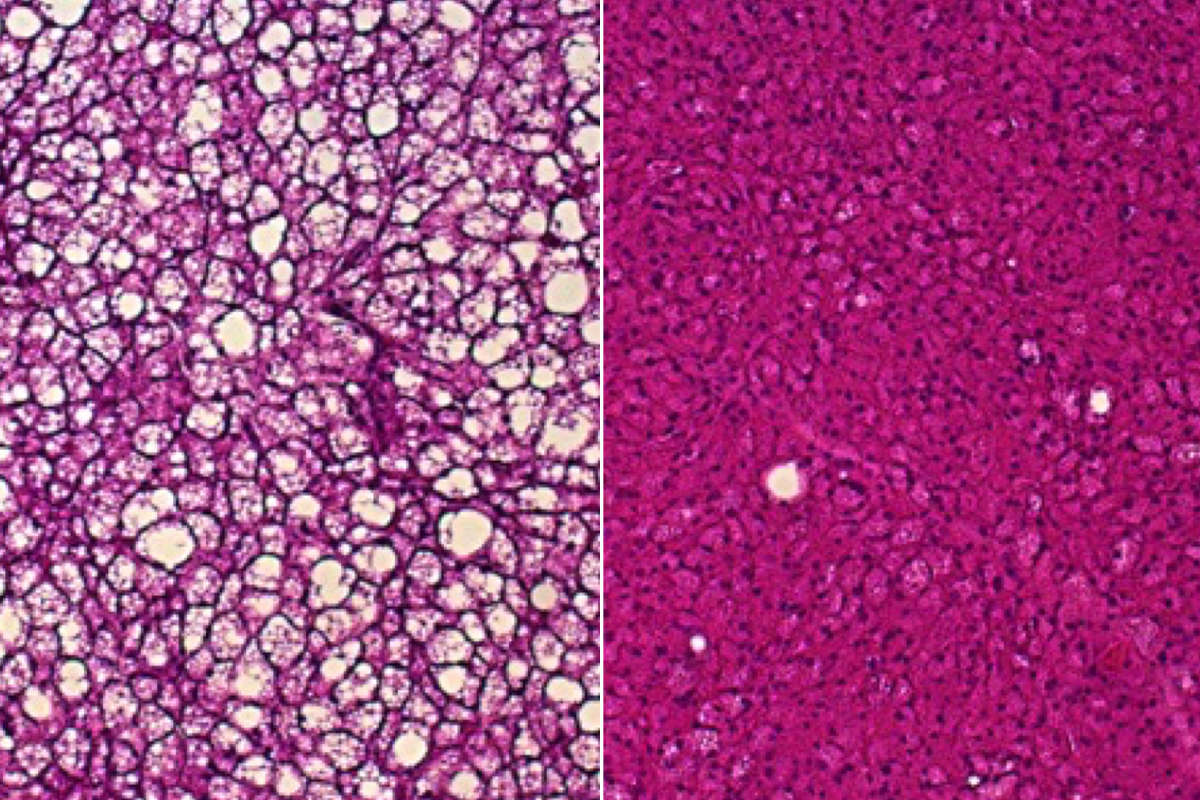

The new study implicates cellular parts called peroxisomes as important alternative heat producers in brown fat. Peroxisomes are small compartments in cells involved in processing fat molecules. When exposed to cold, peroxisomes in brown fat increase in number, the researchers found. This increase is even more dramatic in mice whose mitochondria are deficient in uncoupling protein 1, suggesting that peroxisomes may be able to compensate if mitochondria lose their heat-production ability.

Lodhi and his colleagues discovered that peroxisomes consume fuel and produce heat in a metabolic process that centers on a key protein in these cell parts called acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (ACOX2). Mice missing ACOX2 in brown fat lost some ability to tolerate cold, showing lower body temperatures after exposure to cold compared with typical mice. In addition, compared with typical mice, their tissues did not make good use of the blood sugar-regulating hormone insulin, and they were more prone to obesity when fed high-fat diets.

In contrast, mice genetically engineered to make unusually high amounts of ACOX2 in brown fat showed increased heat production, better cold tolerance and improved insulin sensitivity and weight control when fed the same high-fat diet.

Lodhi Lab

Lodhi LabUsing a fluorescent heat sensor they developed, the researchers found that when ACOX2 metabolized certain fatty acids, brown fat cells got hotter. They also used an infrared thermal imaging camera to show that mice lacking ACOX2 produced less heat in their brown fat.

While human bodies can manufacture these fatty acids, the molecules also are found in dairy products and human breast milk and are made by certain gut microbes. Lodhi said this raises the possibility that a dietary intervention based on these fatty acids — such as a food, probiotic or “nutraceutical” intervention — could boost this heat-production pathway and the beneficial effects it appears to have. He and his colleagues also are investigating possible drug compounds that could activate ACOX2 directly.

“While our studies are in mice, there is evidence to suggest this pathway is relevant in people,” Lodhi said. “Prior studies have found that individuals with higher levels of these fatty acids tend to have lower body mass indices. But since correlation is not causation, our long-term goal is to test whether dietary or other therapeutic interventions that increase levels of these fatty acids or that increase activity of ACOX2 could be helpful in dialing up this heat production pathway in peroxisomes and helping people lose weight and improve their metabolic health.”

$4.87 million grant supports development of sepsis diagnostic device

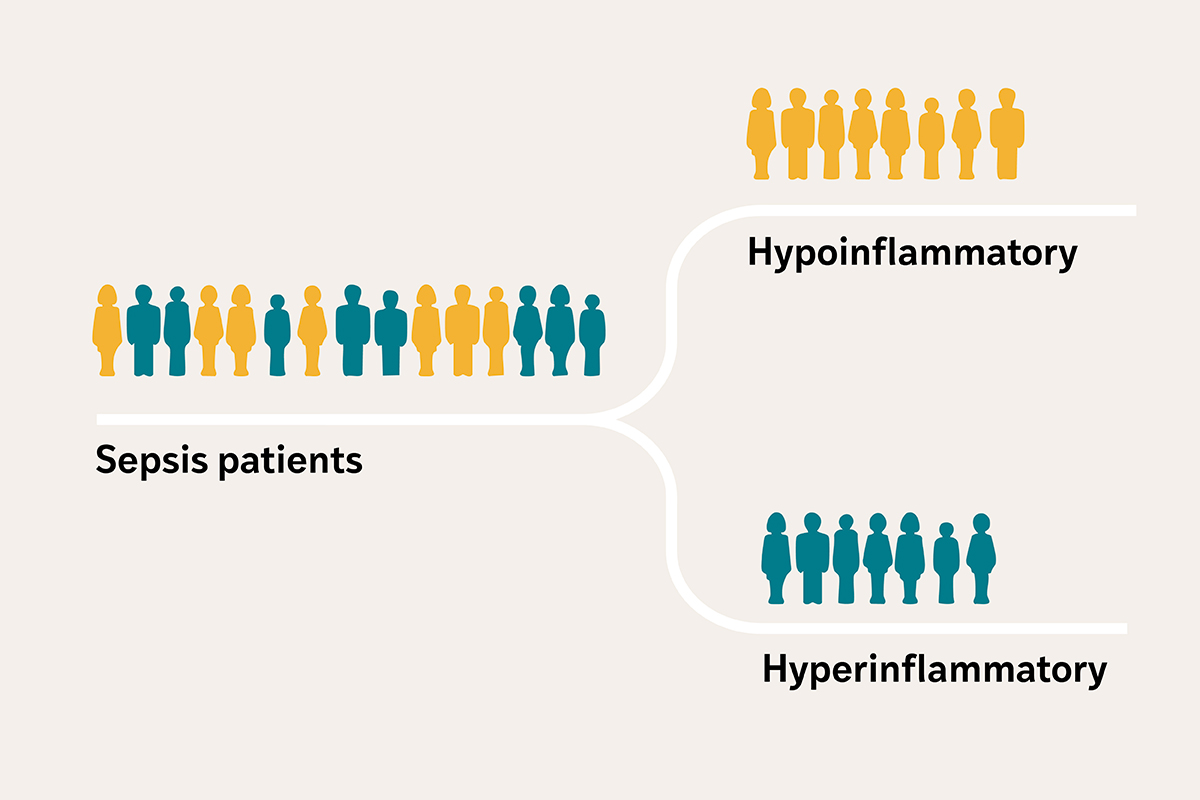

Critically ill patients with sepsis — a condition in which the body’s response to an infection spirals out of control and can lead to organ damage — often arrive at the intensive care unit (ICU) with similar symptoms, such as fever, low blood pressure and kidney failure, among others. But researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have revealed that sepsis patients actually fall into two distinct profiles, based on biological clues in their blood: one with severe inflammation and organ damage, and the other with a less severe response.

Targeting treatments to these biological profiles could help doctors treat people with sepsis more effectively, according to Pratik Sinha, MBChB, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at WashU Medicine. In particular, therapies that were previously deemed unsuccessful may prove to be effective for patients with the severe inflammation profile. But there aren’t clinical tools to accurately and quickly identify these subgroups, which have also been found among patients with other critical illnesses, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, a condition often caused by sepsis that results in severe lung failure.

A research team led by Sinha has received a $4.87 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense to develop a clinical test and handheld device to measure the amount of two biological markers in the blood that can help physicians quickly group patients with sepsis into either a high-risk hyperinflammatory profile or a less severe hypoinflammatory profile.

“Developing a precise test and an affordable device to quickly identify patients with the high-risk hyperinflammatory profile is crucial for delivering targeted treatments and saving lives in critical situations when time matters,” said Sinha. “A highly portable device will enable deployment in active military and combat zones, where trauma increases the risk of infection and sepsis.”

Patient subgroups may advance sepsis care

Each year in the U.S. alone, at least 1.7 million people develop sepsis, and roughly 21% of them die. Included in that statistic are military personnel with serious infections due to trauma inflicted in combat. The mortality rate increases to around 50% in patients with the hyperinflammatory profile of sepsis. Treatment includes antibiotics to fight the infection and supportive therapy for organs that have endured damage, but this approach misses an important piece, according to Sinha.

“Current treatments don’t address the body’s dysregulated response to the infection,” he said. “The challenge in delivering effective treatments is the variability in the severity of the biological response among patients with similar symptoms.”

An earlier study of 3,000 people with critical illness by Sinha and his colleagues, published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, found that the blood levels of two inflammatory cytokines — interleukin-8 (IL-8) and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFR-1) — were reliable indicators of whether the person has a high or low inflammatory response. Inflammatory cytokines are small molecules that cells use to communicate and that can either promote or reduce inflammation.

Many treatments tested in clinical trials on a collective sepsis patient population have been deemed ineffective, Sinha explained. But when the researchers performed a secondary analysis using data from two previously conducted clinical trials and categorizing patients into the two inflammatory profiles, they found that treatment efficacy differed between the two groups. Separating patients into subgroups to enrich clinical trials with patients with similar biological responses could potentially unlock new treatments and repurpose previously failed treatments to improve outcomes in sepsis and other critical illnesses.

Precise, portable, affordable

Supported by this new funding, Sinha is collaborating with Srikanth Singamaneni, PhD, the Lilyan & E. Lisle Hughes Professor at the McKelvey School of Engineering at WashU, to develop a rapid clinical test to capture IL-8 and sTNFR-1 from a few drops of plasma — the liquid component of blood that remains after removing blood cells — and a portable, handheld device to measure the amount of the captured proteins.

This so-called lateral flow test — similar to a COVID-19 rapid antigen test — would be the first to detect IL-8 and sTNFR-1 on a single test strip. Unlike an at-home COVID-19 test, which only indicates the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the researchers’ test incorporates small particles that glow, also referred to as plasmonic fluors, to measure the amount of each inflammatory protein captured on the strip. The researchers will build a device with a camera to detect the glowing particles, and a computer model will quantify the levels to categorize patients into the two subgroups.

“The biomarkers we are trying to detect are found in very small concentrations in the blood,” said Singamaneni, who developed the lateral flow system that incorporates the plasmonic fluors. The plasmonic fluor technology has been patented and licensed to Brightest Bio, a WashU startup formerly called Auragent BioSciences, by WashU’s Office of Technology Management. “Incorporating the fluorescent nanoparticles into the test renders it extremely sensitive, allowing us to not only detect but also accurately measure these biomarkers,” Singamaneni added. “Its sensitivity sets our test apart from other lateral flow assays and is crucial for classifying patients into groups.”

The researchers are developing the test and device to be affordable, accurate and fast. Its compact and portable design will allow it to be deployed directly in a variety of critical care settings, including military bases, combat zones and rural hospitals.

“This tool has the potential to reach patients at the bedside, offering personalized care based on each individual’s specific biological responses,” said Sinha. “We hope to fill a need in critical care that will help bring more effective treatments to more patients.”