Innovative approach helps new mothers get hepatitis C treatment

Hepatitis C, a bloodborne virus that damages the liver, can cause cirrhosis, liver cancer, liver failure and death if left untreated. Despite the availability of highly effective treatments, the prevalence of hepatitis C infection remains high, particularly among women of childbearing age, who account for more than one-fifth of chronic hepatitis C infections globally. Within this group, new mothers are especially vulnerable because treatment has traditionally required outpatient follow-up appointments during the challenging postpartum period.

Now, a new study on an innovative clinical program developed by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that giving postpartum mothers with hepatitis C the opportunity to start antiviral treatment while they are still in the hospital after giving birth, and bringing treatment to bedside prior to discharge, significantly increases their odds of completing the therapy and being cured. The authors found that new mothers who saw an infectious disease specialist and received medication for hepatitis C during their hospital stay were twice as likely to be cured compared with mothers who got a referral to an outpatient follow-up appointment.

The findings appear Sept. 11 in Obstetrics & Gynecology Open.

“We were seeing too many patients fall through the cracks simply because of traditional divisions between what was treated inpatient — labor and delivery — versus outpatient — hepatitis C,” said Laura Marks, MD, PhD, senior author on the study and an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the John T. Milliken Department of Medicine. “We partnered across departments to make sure that when pregnant patients come to Barnes-Jewish Hospital to deliver their babies, they have the option to also get care for a disease that, if left untreated, can lead to cancer.”

Breaking the cycle

Patients are often diagnosed with hepatitis C as part of routine screenings during pregnancy, but treatment has historically been deferred to the postpartum period. However, once women give birth, they don’t always return for follow-up care to start the medication.

To break the cycle, Marks, in collaboration with Jeannie Kelly, MD, an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine & Ultrasound, implemented a “Meds to Beds” approach: Instead of referring patients with hepatitis C to outpatient follow-up care after discharge, the obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine care team would begin the process required for an infectious disease specialist to initiate treatment before the patient was discharged.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this collaborative approach, Marks and first author Madeline McCrary, MD, an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases, reviewed medical records of 149 mothers who delivered babies at Barnes-Jewish Hospital between January 2020 and September 2023 and had tested positive for hepatitis C. Depending on the timing and availability of infectious disease specialists, the women either received immediate hepatitis C treatment while still in the hospital after giving birth or got a referral for an appointment at an outpatient infectious disease clinic or hepatology clinic after their discharge.

Overall, two-thirds of the patients who began treatment in the hospital successfully completed the full course of treatment — 2-3 months of antiviral medication — compared with about one-third of the outpatient referral group. The researchers found that over half of postpartum mothers in the outpatient referral group did not attend the follow-up appointment. The researchers measured successful treatment completion with a lab test confirming that the patient was no longer positive for hepatitis C or with a patient’s report that they had taken the full course of antiviral medication.

“Curing hepatitis C in these mothers has a huge ripple effect — it protects their health, their families and their future pregnancies,” Kelly said. “That’s why we partnered with our infectious disease colleagues to rethink how we could close the gaps in treatment. This new study shows that simply bringing the medication to the patient’s bedside right after delivery dramatically reduces the number of patients lost along the way.”

WashU Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases and Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine have also partnered to integrate infectious diseases care into obstetrics clinics, including implementing new guidelines endorsing shared decision-making around treating hepatitis C during pregnancy.

Exporting the ‘Meds to Beds’ program

Marks, Kelly and colleagues are working to train doctors at WashU Medicine to deploy this interdepartmental “Meds to Beds” program, not only for postpartum mothers but for all patients with untreated hepatitis C. Since 2023, WashU Medicine doctors led by Marks have built up a hepatitis C virus care navigation and treatment program at Barnes-Jewish that incorporates the “Meds to Beds” model and arranges for expedited post-treatment follow-up in local communities to ensure patients are cured. The program has delivered medications to bedside for more than 200 patients, representing an important advance in hepatitis C care.

Beyond WashU Medicine and Barnes-Jewish, Marks points to the future exportability of the new approach, which could also be applied to other infectious diseases.

“We can’t be afraid to try a new model of care when what we stand to gain is better health for the whole community,” Marks said. “We’re teaching our trainees to treat what’s in front of them, especially communicable diseases. As they’re completing the program here, we’re seeing them get recruited to bring this successful model elsewhere. It’s a gradual process, but based on the success we’re already seeing, this momentum will continue to build over time.”

AI-generated medical data can sidestep usual ethics review, universities say

Microbiome instability linked to poor growth in kids

Malnutrition is a leading cause of death in children under age 5, and nearly 150 million children globally under this age have stunted growth from lack of nutrition. Although an inadequate diet is a major contributor, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found over a decade ago that dysfunctional communities of gut microbes play an important role in triggering malnutrition.

Now, in work done in collaboration with the Salk Institute and UC San Diego, WashU Medicine researchers have discovered that toddlers in Malawi — among the places hardest hit by malnutrition — who had a fluctuating gut microbiome showed poorer growth than kids with a more stable microbiome. All of the children were at high risk for stunting and acute malnutrition.

“We know gut microbes are important mediators of malnutrition,” said Mark J. Manary, MD, the Helene B. Roberson Professor of Pediatrics at WashU Medicine, an internationally regarded expert in malnutrition and co-corresponding author on the new study. “By contributing to our understanding of how changes in gut microbes directly contribute to the condition, we pave the way for new methods to diagnose and treat millions of affected children worldwide.”

The findings, published September 9 in Cell, establish a pediatric microbial genome library — a public health database containing complete genetic profiles of 986 microbes from fecal samples of eight Malawian children collected over nearly a year that can be used for future studies to help predict, prevent and treat malnutrition.

Better growth with a stable gut microbiome

More than two decades ago, Manary became a key player in introducing a peanut butter-based, therapeutic food to battle severe acute undernutrition in Malawi, a country in sub-Saharan Africa where 37% of children are affected by stunting. He developed and clinically tested the high-calorie, nutrient-rich paste, which has saved thousands of lives since its adoption as the global standard of care for severe acute malnutrition.

Children who survive the condition often face ongoing challenges in metabolism, bone growth, immune function and brain development. Providing food so that children have enough nutrients to recover isn’t enough on its own to help them grow and thrive, Manary explained.

Among other effects, malnutrition causes an imbalance in the gut microbiome, the community of bacteria and other microorganisms living in the intestines, reducing beneficial microbes and increasing disease-causing ones. The researchers surmised that improving the health of malnourished children may lie in understanding the changes in a gut landscape that is composed of hundreds of bacterial species.

To understand microbial patterns associated with child growth, the researchers sequenced the genomic material from 47 fecal samples collected over 11 months from eight toddlers, who had previously been enrolled in a clinical trial testing the effect of legume-based complementary foods on reducing or reversing environmental enteric dysfunction, a chronic condition that affects the small intestine, and poor growth.

The children chosen for the study were between 12 and 24 months old and had either improving or worsening length-for-age scores (LAZ), an indicator of growth that measures children’s heights against the expected averages for their age and sex. The researchers found that children with a collection of microbial genomes that remained stable — meaning, the microbial population did not undergo drastic changes — showed better growth compared to those with unstable microbial composition, suggesting that gut microbiome stability may be beneficial for supporting growth in children. Measuring such changes, Manary explained, may possibly be used to assess gut health.

Building genomic libraries

The study used a modern genetic sequencing technique known as long-read sequencing to reconstruct complete microbial pangenomes, which include the genetic material of all members of a microbial species. This approach captured 50 times more complete microbiota genomes compared to the traditional method and provided a more comprehensive genetic view of the microbial communities in children at high risk for stunting and acute undernutrition.

“Stunting and acute undernutrition are defined by easily measured, physical measurements, which result from complex and diverse underlying processes,” said co-senior author Kevin Stephenson, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at WashU Medicine. “Improved resolution and accuracy in identifying microbial communities, how they change, and what they are doing may shed light on otherwise unmeasurable facets of undernutrition as well as the role the gut microbiome plays in causing it.”

The technique made it possible to generate the study’s novel pediatric microbial genome library. The researchers optimized a long-read sequencing workflow that other scientists can adapt to build genome libraries for various applications and is amendable to research performed in remote laboratories operating in difficult-to-access locations.

“When applied in remote, field-based molecular laboratories, the genome sequencing and pangenomic approaches we developed can deliver real-time insights not only into pandemic surveillance, antibiotic resistance and infectious disease, but also into agricultural productivity, environmental monitoring and biodiversity conservation,” said senior co-corresponding author Todd Michael, PhD, a research professor at Salk. “It’s a powerful technological advance that expands the reach of genomics and sets a new standard for scientific research in the field.”

Kelly to lead Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Ultrasound

Jeannie Kelly, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has been named the new director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine & Ultrasound. Her new appointment took effect on March 1, 2025, after she served as the interim director since September 2024.

“Dr. Kelly is a superb clinician and researcher who shows exceptional compassion for patients and their families,” said Dineo Khabele, MD, the Mitchell & Elaine Yanow Professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. “Her new leadership position is a testament to her expertise and unwavering commitment to drive change in maternal-fetal health. In her new role, she will undoubtedly elevate our department’s practice to advance the maternal-fetal medicine field.”

Kelly is a renowned expert in the care of women with opiate use disorders during pregnancy. She pioneered an innovative concept for care and now leads the Washington University Clinic for Acceptance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) in Pregnancy, which provides prenatal care, substance abuse treatment and extended postpartum support for pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Her dedication to maternal and fetal health has earned her multiple awards for her outstanding care for mothers and newborns affected by opioids, as well as for providing superior patient experiences.

Kelly’s clinical expertise drives her research focused on the impact of opioid use during pregnancy. She leads projects funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), contributing valuable insights to opioid use research. Recognized for her contributions to medicine and research, she received the WashU Medicine Dean’s Impact Award in 2023. As a member of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s Practice Advisory Board and the Committee for Reproductive Health, Kelly continues to make significant contributions locally and nationally through her leadership, clinical acumen, research focus and commitment to education.

During the height of the pandemic, Kelly developed adaptive algorithms for the management of COVID-19 in pregnancy and helped lead the COVID-19 obstetric response across all Barnes-Jewish Hospital facilities. Her expertise in opiate use disorder and COVID-19 in pregnancy has led to changes in clinical care both locally and nationally.

“WashU Medicine leads in all aspects of medicine, by providing exceptional clinical care, conducting innovative research and training the next generation of medical and scientific leaders,” said Kelly, who previously held the position of associate director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine & Ultrasound. “I am honored to be leading a division that makes a difference every day by constantly searching for ways to improve the care that we give to patients through cutting-edge technology or therapies that change lives.”

Kelly is committed to medical education, for which she has earned local and national teaching awards. She mentors students, residents, fellows and faculty members who strive to emulate her skills and compassion.

Kelly earned her medical degree from Columbia University. She completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology and her fellowship in maternal-fetal medicine at Tufts Medical Center, where she also obtained a master’s degree in clinical and translational science.

Habits to Remain Injury-Free, According to Physical Therapists

Colon cancer is rising in people under 50. Does lifestyle have anything to do with it?

Pollina named Vallee Foundation Scholar

Elizabeth Pollina, PhD, an assistant professor of developmental biology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has been named a 2025 Vallee Scholar by the Vallee Foundation, an international organization that supports the advancement of biomedical research and medical education globally.

She is one of six early-career researchers recognized this year for their extraordinary accomplishments and future promise in conducting bold and innovative basic biomedical research. Each scholar will receive $400,000 over four years to support their research.

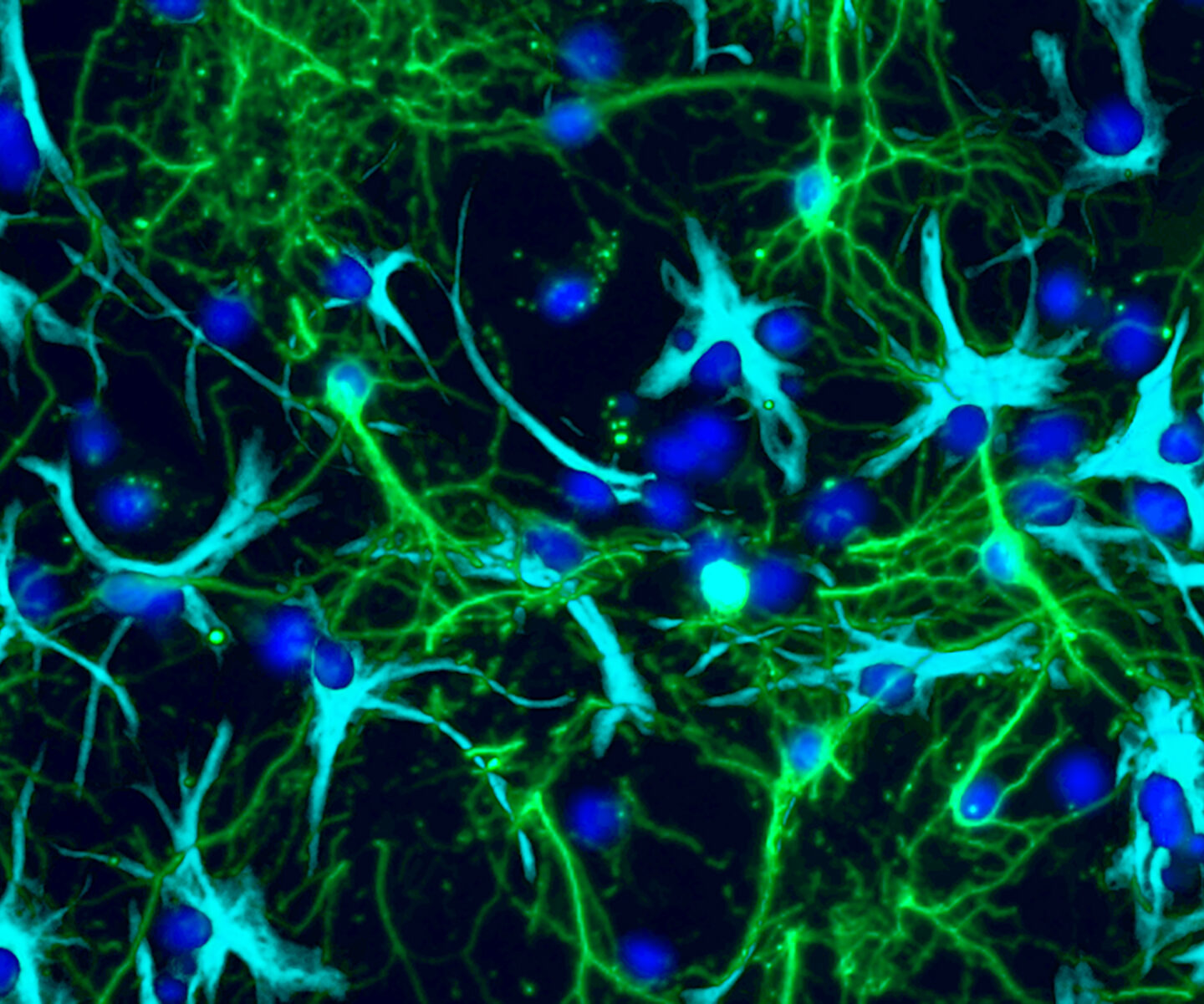

Pollina’s team studies how the genome protects itself from normal wear and tear, seeking ways to safeguard vulnerable cell types from the effects of aging and degeneration.

In particular, she and her team are interested in preventing or repairing DNA damage in the vital and diverse cells of the brain. The flexibility that allows brain cells to send electrical signals and form new circuits governing learning, memory and behavior also can trigger DNA damage, raising questions about how cells protect their genomes over time and how organisms find a balance between the benefits of their brain cells’ electrical activity and the risks this poses to the integrity of their DNA. The research could shed light on cognitive decline in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. It also has implications for developing future therapeutics, identifying new ways to intervene to protect these cells from damage or nurture their repair.

Study sheds light on how pediatric brain tumors grow

The most common type of brain tumor in children, pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), accounts for about 15% of all pediatric brain tumors. Although this type of tumor is usually not life-threatening, the unchecked growth of tumor cells can disrupt normal brain development and function. Current treatments focus mainly on removing the tumor cells, but recent studies have shown that non-cancerous cells, such as nerve cells, also play a role in brain tumor formation and growth, suggesting novel approaches to treating these cancers.

Scientists have long known that a nerve cell signaling chemical called glutamate can increase growth of cancers throughout the body, but despite years of investigation, they haven’t figured out exactly how this happens, or how to stop it. Now, an interdisciplinary team of researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has uncovered how glutamate regulates pediatric brain tumor growth. Using tumor cells isolated from patient PA samples, they found that PA cells hijack the function of proteins on cells’ surface that normally respond to glutamate, called glutamate receptors. Instead of transmitting glutamate’s typical electrical signal, these receptors are reprogrammed to send signals to increase cell growth.

They also observed that drugs that block these glutamate receptors — including memantine, which is approved to treat dementia and Alzheimer’s disease — reduced human pediatric brain tumor growth in mice, a finding that points to a potential new treatment opportunity.

The results appear September 1 in Neuron.

“With these kinds of pediatric brain tumors, we just don’t have that many tools in our toolbox for treating patients,” said senior author David Gutmann, MD, PhD, the Donald O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology at WashU Medicine. Gutmann treats patients at Siteman Kids at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “The potential to repurpose drugs that are already in use for other neurological disorders means we may have another trick up our sleeves for treating patients.”

The research team, which included first author Corina Anastasaki, PhD, a research assistant professor of neurology at WashU Medicine, also showed for the first time that glutamate receptors abnormally couple with growth receptors in PAs to fuel the tumors. The findings offer a roadmap for future studies to explore if the same process is happening in different types of cancers.

New uses for familiar tools

Glutamate is what is known as a neurotransmitter, a molecule that nerve cells, including neurons in the brain, use to communicate with each other. On their path to understand how glutamate helps brain tumors grow, Gutmann, who is also the director of the Neurofibromatosis Center at WashU Medicine, and Anastasaki worked closely with collaborators across WashU Medicine — including in neurosurgery, pediatrics, genetics, neuropathology, biostatistics and more — to acquire and analyze samples of PAs that had been surgically removed. They found that these PA cells had unusually high levels of glutamate receptors.

By testing how glutamate affected these tumors, the researchers discovered that glutamate increased PA cell numbers by kicking off a chain reaction inside the tumor cells that urged cells to divide. These findings suggest that tumor cells exploit normal brain-cell interactions to spur their own growth.

“This novel mechanism for tumor growth combines two normal but unconnected brain processes — growth and electrical signaling — in an aberrant way,” Anastasaki said. “Now that we’ve figured out how these cells work and grow, the sky’s the limit for looking at other neurotransmitters and the different avenues of communication between neurons and cancer cells. Understanding that will tell us why tumors grow and behave the way they do. That may lead to us treating them very differently.”

Such new treatments might come from familiar sources. The researchers showed that inhibiting glutamate receptors of tumor cells in mice with PAs — either with medications or by genetically altering the cells — reduced tumor growth. This points to a potential opportunity to repurpose glutamate receptor-targeting drugs such as memantine for the treatment of PAs.

The next steps are to determine whether such medications are safe to use in children with brain tumors and in what amounts they would be effective, Gutmann noted, which will require clinical trials.

“This study provides compelling preclinical data to look at medications that are otherwise safe and approved to treat other neurological conditions,” Gutmann said. “That would enable new therapeutic approaches and could help minimize the damage to a child’s developing brain by reducing engagement between brain cells and tumor cells.”

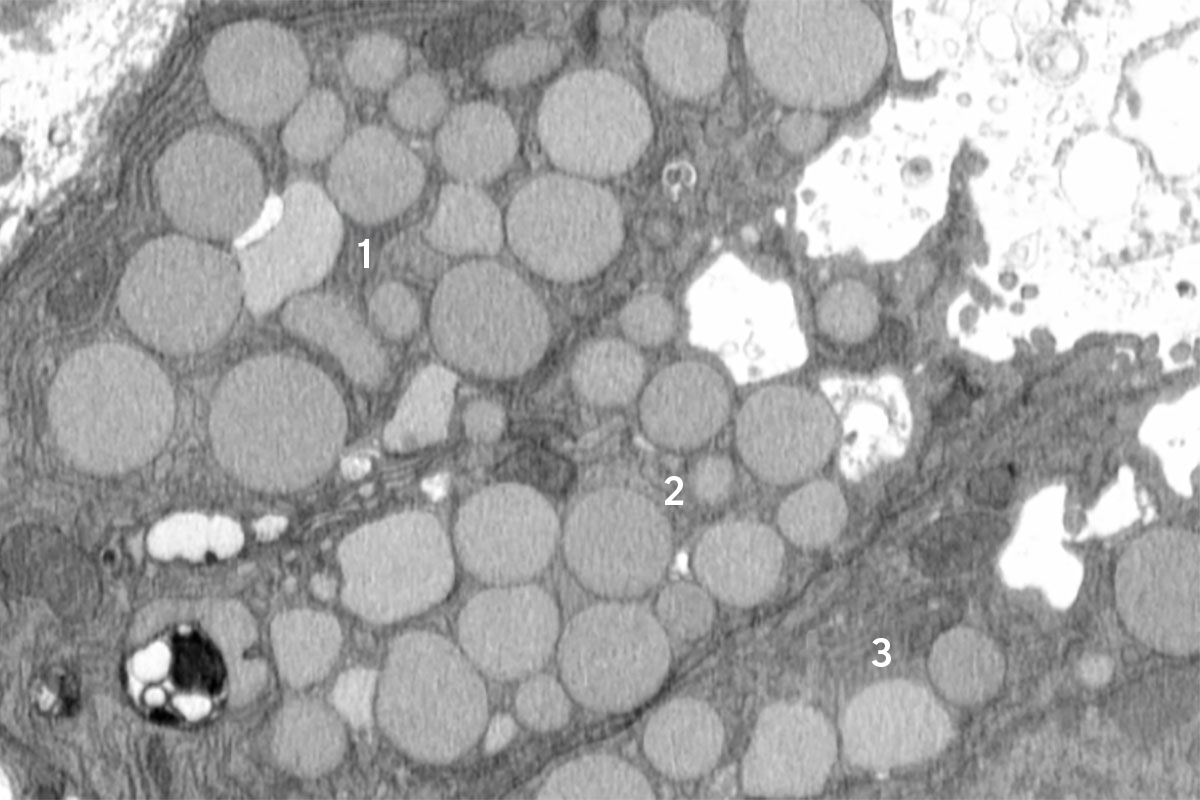

Cells ‘vomit’ waste to promote healing, mouse study reveals

When injured, cells have well-regulated responses to promote healing. These include a long-studied self-destruction process that cleans up dead and damaged cells as well as a more recently identified phenomenon that helps older cells revert to what appears to be a younger state to help grow back healthy tissue.

Now, a new study in mice led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the Baylor College of Medicine reveals a previously unknown cellular purging process that may help injured cells revert to a stem cell-like state more rapidly. The investigators dubbed this newly discovered response cathartocytosis, taking from Greek root words that mean cellular cleansing.

Published online in the journal Cell Reports, the study used a mouse model of stomach injury to provide new insights into how cells heal, or fail to heal, in response to damage, such as from an infection or inflammatory disease.

“After an injury, the cell’s job is to repair that injury. But the cell’s mature cellular machinery for doing its normal job gets in the way,” said first author Jeffrey W. Brown, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at WashU Medicine. “So, this cellular cleanse is a quick way of getting rid of that machinery so it can rapidly become a small, primitive cell capable of proliferating and repairing the injury. We identified this process in the GI tract, but we suspect it is relevant in other tissues as well.”

Brown likened the process to a “vomiting” or jettisoning of waste that essentially adds a shortcut, helping the cell declutter and focus on regrowing healthy tissues faster than it would be able to if it could only perform a gradual, controlled degradation of waste.

As with many shortcuts, this one has potential downsides: According to the investigators, cathartocytosis is fast but messy, which may help shed light on how injury responses can go wrong, especially in the setting of chronic injury. For example, ongoing cathartocytosis in response to an infection is a sign of chronic inflammation and recurring cell damage that is a breeding ground for cancer. In fact, the festering mess of ejected cellular waste that results from all that cathartocytosis may also be a way to identify or track cancer, according to the researchers.

A novel cellular process

The researchers identified cathartocytosis within an important regenerative injury response called paligenosis, which was first described in 2018 by the current study’s senior author, Jason C. Mills, MD, PhD. Now at the Baylor College of Medicine, Mills began this work while he was a faculty member in the Division of Gastroenterology at WashU Medicine and Brown was a postdoctoral researcher in his lab.

In paligenosis, injured cells shift away from their normal roles and undergo a reprogramming process to an immature state, behaving like rapidly dividing stem cells, as happens during development. Originally, the researchers assumed the decluttering of cellular machinery in preparation for this reprogramming happens entirely inside cellular compartments called lysosomes, where waste is digested in a slow and contained process.

From the start, though, the researchers noticed debris outside the cells. They initially dismissed this as unimportant, but the more external waste they saw in their early studies, the more Brown began to suspect that something deliberate was going on. He utilized a model of mouse stomach injury that triggered the reprogramming of mature cells to a stem cell state all at once, making it obvious that the “vomiting” response — now happening in all the stomach cells simultaneously — was a feature of paligenosis, not a bug. In other words, the vomiting process was not just an accidental spill here and there but a newly identified, standard way cells behaved in response to injury.

Although they discovered cathartocytosis happening during paligenosis, the researchers said cells could potentially use cathartocytosis to jettison waste in other, more worrisome situations, like giving mature cells that ability to start to act like cancer cells.

The downside to downsizing

While the newly discovered cathartocytosis process may help injured cells proceed through paligenosis and regenerate healthy tissue more rapidly, the tradeoff comes in the form of additional waste products that could fuel inflammatory states, making chronic injuries harder to resolve and correlating with increased risk of cancer development.

“In these gastric cells, paligenosis — reversion to a stem cell state for healing — is a risky process, especially now that we’ve identified the potentially inflammatory downsizing of cathartocytosis within it,” Mills said. “These cells in the stomach are long-lived, and aging cells acquire mutations. If many older mutated cells revert to stem cell states in an effort to repair an injury — and injuries also often fuel inflammation, such as during an infection — there’s an increased risk of acquiring, perpetuating and expanding harmful mutations that lead to cancer as those stem cells multiply.”

More research is needed, but the authors suspect that cathartocytosis could play a role in perpetuating injury and inflammation in Helicobacter pylori infections in the gut. H. pylori is a type of bacteria known to infect and damage the stomach, causing ulcers and increasing the risk of stomach cancer.

The findings also could point to new treatment strategies for stomach cancer and perhaps other GI cancers. Brown and WashU Medicine collaborator Koushik K. Das, MD, an associate professor of medicine, have developed an antibody that binds to parts of the cellular waste ejected during cathartocytosis, providing a way to detect when this process may be happening, especially in large quantities. In this way, cathartocytosis might be used as a marker of precancerous states that could allow for early detection and treatment.

“If we have a better understanding of this process, we could develop ways to help encourage the healing response and perhaps, in the context of chronic injury, block the damaged cells undergoing chronic cathartocytosis from contributing to cancer formation,” Brown said.

Thaker to lead Division of Gynecologic Oncology

Premal H. Thaker, MD, the David & Lynn Mutch Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, has been named director of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Her new role began June 1.

As director, Thaker oversees the division’s efforts to conduct research, educate the next generation of gynecologic oncologists as well as care for patients with dignity, assurance and compassion as they address the challenges of a cancer diagnosis.

“After a rigorous national search and serving for almost 18 months as interim director, Dr. Thaker was identified as the leading candidate,” said Dineo Khabele, MD, the Mitchell & Elaine Yanow Professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. “Since she joined our department in 2006, Dr. Thaker has been distinguishing herself through life-saving research in gynecologic oncology, mentoring learners and faculty alike and ensuring her patients get the utmost cutting-edge care. We are excited to embark on continued growth and expansion of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology under her leadership.”

Thaker earned her undergraduate degree in biology from Villanova University in Villanova, Pennsylvania, and her medical degree from Allegheny University of the Health Sciences in Philadelphia in a combined BA/MD program. She completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, and her fellowship in gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. While there, she began her landmark research that explored biobehavioral influences on ovarian cancer progression. She also holds a master’s degree in cancer biology from the University of Texas Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, also in Houston. Additionally, Thaker received training in laparoscopic lymph node dissection at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in Germany.

She joined WashU Medicine in 2006 as an assistant professor and was promoted to professor in 2018. She continues to see patients at the high-volume gynecologic oncology practice she helped build. She offers complex laparoscopic, robotic and open surgical procedures as well as state-of-the art chemotherapy and other targeted therapies. Since 2021, her name has consistently appeared on the Castle Connolly and St. Louis Top Doctors lists since 2013 as a testament to her outstanding patient care. She is widely published in her field and has presented her work at academic meetings and conferences locally, nationally and internationally. Thaker has served as the principal investigator on nine national clinical trials related to gynecologic oncology. She has been inducted into both the American Gynecological & Obstetrical Society and the Society of Pelvic Surgeons. She has also served as the director of Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Research since 2019.

“So many mentors have come before me, blazing a path toward better outcomes for the women we treat,” Thaker said. “And I wouldn’t be here without them. They encouraged my relentless pursuit of care that goes beyond a patient’s diagnosis, as well as translational research and clinical trials that push the bounds of how we can help them. I’m truly humbled and honored to lead this work and division.”

Research explores genetics underlying immune system disorders

Immune disorders include rare genetic conditions that weaken the immune system, leaving patients vulnerable to dangerous infections and other problems such as autoimmunity, inflammation and cancer. Despite being a powerful diagnostic tool, genetic testing — which identifies changes, or mutations, in an individual’s genetic material — has uncovered about 550 such conditions but still leaves 70% of people with suspected immune deficiencies undiagnosed.

Megan A. Cooper, MD, PhD, the Anthony R. French, MD, PhD, Professor of Pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has received a five-year, $12.4 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study genetic processes missed by standard genetic testing that may be involved in causing immune disorders in children and adults. This research may reveal new genetic causes of immune disorders and provide answers to patients awaiting a diagnosis.

“The diagnostic rate for rare immune disorders has remained stagnant over the last decade,” said Cooper, an internationally recognized physician-scientist who specializes in diagnosing and treating rare genetic diseases affecting the immune system, especially in children. “Effective treatment depends on understanding the specific problems within a patient’s immune system. A diagnosis enables access to targeted treatments, effective disease management and prevention strategies.”

For patients with suspected immune deficiency, symptoms can be ambiguous and include prolonged fevers after common infections, such as respiratory infections; frequent unusual infections; autoimmune disease; susceptibility to cancers; and severe allergies, among others. No two patients experience the same symptoms, explained Cooper, which makes diagnosing immune disorders challenging.

“I see a lot of patients who are sick all the time,” said Cooper, who collaborates with specialists worldwide to solve puzzling diagnostic cases affecting children. “When we don’t know what is causing their symptoms, we are left with giving them very broad, non-specific therapies that can sometimes be ineffective. This work hopes to provide more families with life-saving molecular diagnoses that can guide treatment.”

Uncovering novel genetic causes

Genetic testing finds changes in an individual’s DNA and is effective at detecting errors that are present from the start of development and affect all the cells in the body. Mutations that cells acquire over time, which are rare in the body or affect only specific tissue types, are much harder to detect with standard genetic sequencing.

To help solve this problem, Cooper and two collaborators at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City — Dusan Bogunovic, PhD, an immunologist and professor of pediatrics and a co-principal investigator on the grant, and Joshua Milner, MD, an immunologist and professor of pediatrics — will use a technique called deep sequencing, which allows them to examine genes in patients with a level of detail and accuracy that standard sequencing cannot achieve, helping to identify changes that affect even a small number of cells.

They also will study, under Bogunovic’s leadership, a unique genetic process that can cause some, but not all, family members to be affected by illness, despite all members inheriting one faulty and one healthy copy of a gene. Whether a family member remains healthy or develops disease depends on which gene copy remains active. The study aims to find genes in the immune system that follow such a pattern and better understand the factors that control it.

The roughly 550 known immune disorders caused by different genetic changes result in symptoms that are highly variable and unique to individuals. Another focus area, led by Milner, seeks to explore how combinations of common genetic changes — rather than single gene mutations — impact an individual’s risk for illness and severity. They will study the effects of these common changes in patient cells, while correlating patient symptoms with the genetic change combination they carry.

The new grant was based on preliminary data that applied deep sequencing to looking for genetic differences in immune disorders. That work was supported by the NIH, St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Children’s Discovery Institute, a collaboration between St. Louis Children’s Hospital, its foundation and WashU Medicine to find innovative, more precise and personalized treatments for a spectrum of childhood diseases.

Other WashU Medicine investigators involved include Obi L. Griffith, PhD, a professor, and Malachi Griffith, PhD, an associate professor, both in the John T. Milliken Department of Medicine.